Assessing the Pulse of the Next Farm Bill Debate

Thirteen agricultural economists put together short papers describing issues that will surface during the writing of the next farm bill. For each issue, the author describes the “policy setting” and details “farm bill issues” that likely will arise during negotiations. Each issue then has a “what to watch for” summary. These papers, along with an overview, are presented in this article.

Issues Addressed in the Next Farm Bill

The following issues, along with a summary, were addressed by the authors:

- Overview

- Field Crop Safety Net: Insurance Programs

- Field Crop Safety Net: Crop Commodity Programs except Cotton

- Field Crop Safety Net – Cotton

- Dairy Safety Net

- Livestock and Specialty Crop Safety Net

- Nutrition Safety Net

- Environmental Services

- Rural Development

- Research and Extension

- Trade

- Energy

Overview: Assessing the Pulse of the Next Farm Bill

Prepared by: Carl Zulauf, Gary Schnitkey, and David Orden

Historical Overview: Since 1933 the Farm Bill has been the preeminent federal social contract between U.S. society at large and the U.S. rural sector. Began almost exclusively to provide economic assistance to economically impoverished farm families, it has evolved into a multifaceted social contract touching almost every American, both rural and urban. It includes nutrition, commodity, and crop insurance titles that provide safety nets to low-income households, crop farms, and livestock farms. Goals such as environmental quality, research and extension, rural development, trade expansion, and bioenergy production are also promoted.

Budget Overview: A common presumption is that a tight budgetary environment will make negotiations on the next farm bill difficult. However, a tight budget can also facilitate negotiations by encouraging policy actors to work together, often to protect desired, existing programs. Moreover, budget developments are positive. The 2014 commodity and crop insurance programs are costing less than Congressional Budget Office forecasts, and an improving economy is reducing spending on SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) and other nutrition programs. Nutrition programs make up over 70% of Farm Bill spending. In addition, the on-going, post-2014 farm bill debate over cotton and dairy policy may be resolved via the appropriations process, offering a potentially larger budget baseline for commodity programs. In short, the budget may end up being less of a constraint than has been largely portrayed in the run up to the farm bill debate.

Issues Overview: The next farm bill is being framed by (1) lower farm prices and revenue than when the 2014 Farm Bill was written, (2) a 2016 election underscored by a disaffected American rural sector, and (3) President Trump’s focus on trade as a front-line issue. Point 1 implies that redistribution of spending from farm safety net programs to other farm bill titles is unlikely. Point 2 implies programs targeted to the non-farm rural sector could be a defining feature of this farm bill, particularly given that the next farm bill likely will be written in an election year. While the President’s perspective on trade has caused concern, American agriculture has come to embrace a refocus on trade expansion given a mature domestic market for food and a bioenergy market that appears to have less potential than when the last three farm bills were written. The refocus on trade is also prompting discussions on the role of research and extension, particularly as it pertains to productivity.

Summary: All farm bills are a portfolio of past and new programs and issues. The blend varies by farm bill. This farm bill looks to tilt toward continuation or limited modification of past programs and issues covered. However, an intriguing set of new issues or new perspectives on past issues also exist. We hope the 11 one-page summaries of farm bill topics that comprise the rest of this farmdoc daily post provide you with insights into the next installment of the most important social contract between the U.S. and its rural communities.

Issues Summary: Crop Insurance

Prepared by: Gary Schnitkey, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Policy Setting: Crop insurance has grown in significance as the emphasis of farm bills has moved from providing income support for farmers to providing risk management. Contributing to the growth and significance of the Federal program have been introductions of revenue insurance products, increases in coverage levels, introductions of policies for more crops, introduction of whole farm and livestock policies, and increases in Federal support for premiums. Many farmers view crop insurance as the most important risk management program offered by the Federal government. According to Congressional Budget Office projections, Federal expenditures on crop insurance will average $7.7 billion annually from 2018 to 2027, compared with $6.2 billion for commodity title programs and $6.0 billion for conservation programs (Coppess, et al.).

Farm Bill Issues: Previous farm bills modified the crop insurance program by enhancing risk coverages offered or decreasing the cost of the crop insurance program to farmers. For example, the 2014 farm bill introduced cotton STAX, Supplemental Coverage Option (SCO), and Yield Exclusion (Schnitkey and Zulauf). It is difficult to anticipate whether new provisions will be debated in the next farm bill.

Because of the size of Federal expenditures, the crop insurance program could face pressures in a budget cutting environment. Reductions to specific provisions of the crop insurance program could be proposed such as reducing subsidies for the harvest price option, reducing subsidies for high coverage levels, and reducing provisions that increase guarantees (i.e., size of transition yields or existence of Yield Exclusion). Each of these specific provisions have differential impacts on crops and regions and, as such, will face regional opposition. For example, reducing subsidies on harvest price option and high coverage levels would have a higher impact on corn and soybeans in the Midwest. Reducing provisions that increase guarantees would have a higher impact on higher yield risk areas such as the Great Plains. Another option for reducing expenditures is an across the board cut in premium support, which would impact all regions and crops (Schnitkey and Zulauf).

Amendments to previous farm bills – none of which passed – would have introduced means testing to crop insurance. Commodity title programs are subject to means testing, providing a further rational for means testing of crop insurance. President Trump’s budget introduced a $40,000 limit on premium support per individual and an Adjusted Gross Income test. Similar amendments likely will introduced in the upcoming farm bill.

Under the 2014 farm bill, conservation compliance was introduced for the first time to the crop insurance program. As crop insurance has become more important relative to commodity title programs, conservation and environmental groups have focused more attention on the crop insurance title.

What to Watch: (1) New proposals for enhancing risk protection offered by crop insurance, (2) Proposals to reduce expenditures on crop insurance, (3) Proposals to introduce means testing and (4) Proposals to incorporate more conservation provisions into crop insurance.

Issues Summary: Field Crop Safety Net — Crop Commodity Programs except Cotton

Prepared by: Carl Zulauf, Emeritus, Ohio State University

Policy Setting: Although the 2014 Farm Bill crop commodity programs terminate with the 2018/19 crop year, commodity programs will continue since they revert to the 1938 and 1949 laws that are amended by each farm bill. The permanent laws generate support prices far above current market prices for some commodities, notably milk. Congress thus will likely enact a new farm bill or extend the current one. Historically, the farm bill is written with broad, bipartisan support (Orden and Zulauf), an expectation that continues for the forthcoming farm bill. However, if conservative and moderate Republicans can agree on a general approach for passing authorization legislation and reforming entitlement programs by passing a health care bill, the farm bill may take a more partisan approach.

Farm Bill Issues: While redistribution of commodity program spending to other farm bill titles is an evolutionary trend since 1970, counter-trend farm bills are written if farm prices/income are low (Zulauf and Orden). It is unclear if current prices/income are low or normal, but they are clearly less than when 2014 Farm Bill was written. The latter perspective is likely to frame the debate, implying commodity baseline redistribution is unlikely. On the other hand, changing commodity programs will likely require finding money within the commodity or insurance titles. Funds can be found by adjusting support parameters, but each adjustment will encounter resistance. Options include a mandatory update of base acres. Over time, base acres have migrated to crops with the highest payment/acre (Zulauf and Schnitkey).

Changes to cotton and milk policy and potential equity issues across crops and programs cloud the current sentiment that crop changes (other than cotton) will be limited. Resolving cotton and dairy policy before the farm bill is important because doing so adds baseline for these policies. An early resolution seems possible (Good). Peanuts and rice are expected to have higher future payments/acre, in part due to a high reference price relative to market price (Coppess, et al). Payment/acre is only one perspective on equity, but history suggests a divisive debate could occur (Schnitkey and Zulauf). Current prices of most crops are close to or below their reference prices. Thus, participation will likely shift notably to PLC (Price Loss Coverage) if, as history suggests, farms can elect a new program starting with the 2019/20 crop year. Debate is thus likely on adjusting ARC (Agricultural Risk Coverage) so it is more competitive with PLC.

What to Watch: (1) Are cotton and dairy policy resolved prior to the farm bill? (2) Fall 2017 crop prices –important to the commodity title baseline. (3) Health care policy debate. (4) Interplay between crop and program equity — PLC’s higher expected cost provides an umbrella to change ARC without increasing the commodity title baseline by much, which in turn may help resolve the crop equity issue.

Issues Summary: Field Crop Safety Net — Cotton

Prepared by: John Robinson, Texas A&M University

Policy Setting: In response to the WTO Brazil case, the 2014 farm bill minimized cotton’s longstanding participation in Title I farm programs to the marketing loan assistance program. Title XI of the 2014 farm bill created the Stacked Income Protection Plan (STAX) for cotton as a supplemental county-based revenue insurance plan with the same annual price establishment and similar intra-seasonal price risk protection as for Revenue Protection, and the Supplemental Coverage Option. Recently the cotton industry has sought protection from exposure to inter-seasonal, sub-profitable prices which have dominated since 2014. This effort focused on USDA, and subsequently on Congressional Appropriators, to designate cottonseed as an oilseed eligible for ARC/PLC programs. As of July 21, the Senate Appropriations Committee passed an FY18 Agricultural Appropriations bill with such a designation. Enhancing cotton’s safety net has generated an academic discussion of various issues involving rationale and potential impacts (Zulauf, Schnitkey, Coppess, and Paulson; Hudson).

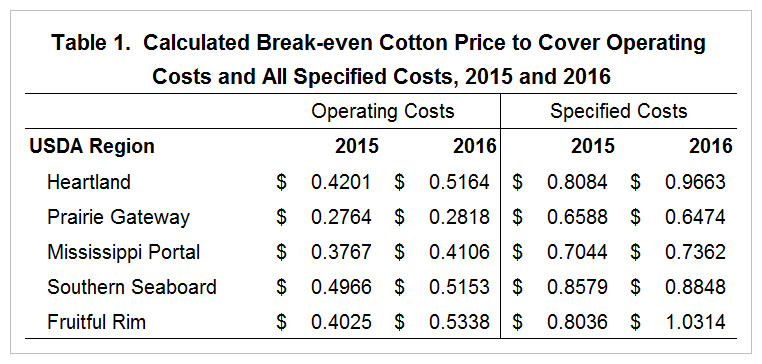

Farm Bill Issues: One major issue is whether U.S. cotton represents enough producers, acreage, economic impact, political organization, and congressional leadership to remain a beneficial source of political base broadening for the farm lobby. The latter is presumably important to defend against non-commodity farm bill interest groups and WTO complaints (of which U.S. cotton has not been a unique target). A second overarching issue is the adequacy of cotton’s safety net in relation to its own cost structure. The loan rate for cotton does not cover total cost of production (Table 1, USDA-ERS). In some years and regions, the loan rate barely supports a price above the short run decision to shut down (Table 1, USDA-ERS). STAX and other insurance products are hindered during multi-year price trends at sub-profitable levels. The high level and variability of cotton production costs has led to an emerging farm finance issue in cotton growing regions. A third major issue is the constraint on federal budget spending which poses a challenge for enhancing cotton’s safety net and maintaining one for other crops.

What to Watch: 1) If FY18 appropriations effectively designate cottonseed as an oilseed, will that establish a sufficient baseline for Title 1 spending on cotton in the farm bill? 2) If not, will the collective political needs of the farm lobby and the House leadership still influence the farm bill process to create ARC/PLC programs for cotton? 3) If so, how will a baseline for cotton Title I spending be determined, and how will this influence all Title I support program parameters?

Issues Summary: Dairy Safety Net

Prepared by Andrew Novakovic, Cornell University, and Christopher Wolf, Michigan State University

Policy Setting: From the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 to the Trade Agreements Extension Act of 1951, the US dairy sector slowly developed a formidable set of policy tools that gave it 1) farm price regulation in the form of Federal Milk Marketing Orders, 2) price supports, and 3) tight import quotas. Slowly these impactful, historic programs are being eroded and dismantled. Import quotas were replaced with the more generous market access requirements and more modest tariff rate quotas of the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture. Since 1996, the US dairy sector has become an open economy and emerged as the second largest dairy exporting country in the world. Milk price support legislation still exists in permanent law, the Agricultural Act of 1949, but that tool essentially was abandoned in 1990 and replaced by income supports that have provided less support to dairy farmers. Marketing Orders remain much as they have been, perhaps in no small part because they do not require reauthorization within the farm bill.

The Agricultural Act of 2014 introduced a new income support program called the Margin Protection Program for Dairy Producers or MPP-Dairy. Although it should properly be thought of as income support, this program is designed to mimic a net revenue risk management program. A national “margin” is calculated as the difference between the national average price of milk and a cost of feeds calculated from prices for corn, alfalfa hay and soybean meal. For a modest fee, any farmer can sign up for “catastrophic coverage” and for increasingly larger “premiums” they can elect higher levels of coverage, ranging up to a value close to a 10-year average margin. MPP-Dairy replaced the Milk Income Loss Contract (MILC), a more straight-forward income subsidy based on a milk price trigger. MILC was judged as insufficient in magnitude and scope. Among the goals for its replacement was to build a new program which recognized that high feed prices can be just as challenging to dairy farms as low milk prices.

Farm Bill Issues: MPP-Dairy first became available in 2015 and has just entered its fourth sign up period. About half of US dairy farmers chose to participate in the program in 2015, and over half of those elected “buy-up” coverage. Believing that the program did not pay out as generously in 2015 as it should, the sign-up for 2016 saw only 23% purchase “buy-up” coverage. For 2017 the share fell to less than 8% (percentage of dairy farmers who signed up for the programs). Arguments to the effect that one does not actually want insurance to pay notwithstanding, dairy farmers generally argue that if this new program did not provide income subsidies in 2015 and 2016 then it falls far short of their expectations. Although 2017 was correctly expected to be a year with no payment due to an increasing margin, lack of faith in the program is increasingly evident in the sign-up statistics. Further evidence of farmer disappointment with the program includes the many policy initiatives to reform and improve MPP-Dairy introduced in 2017. The most recent is a significant and fairly costly tweaking of the program that has been levered into the Senate appropriations bill.

What to Watch: At this point, there is no organized interest in legislatively changing Marketing Orders. Dairy trade policy has become a point of discussion with the demise of the TPP and the effort to revisit NAFTA. For the time being, these are Executive Branch agendas with uncertain outcomes. Agriculture advocates and like-minded Members of Congress are primarily focused on doing no harm to trade prospects with our two largest dairy trading partners. Whether or not the aforementioned amendments to MPP-Dairy survive in the final appropriations legislation remains to be seen but the prospects are fairly good.

Issues Summary: Livestock and Specialty Crop Safety Net

Prepared by: Stephanie Mercier, Farm Journal Foundation

Policy Setting: Largely due to their own policy choices over time, U.S. livestock and specialty producers do not benefit from federal farm safety net programs that support their income like field crop or dairy producers.

Until the last few farm bills, rather than pursue direct benefits through the farm bill process, commodity associations representing livestock and horticultural producers primarily focused on maintaining or increasing resources for generally applicable programs which helped to expand the demand for their products, either domestically through nutrition assistance programs such as the school lunch and breakfast programs or internationally through USDA trade promotion programs, such as the Market Access Program (MAP) and the Foreign Market Development Program (FMDP). A small program devoted to helping specialty crop producers address SPS obstacles to their exports, called Technical Assistance for Specialty Crops (TASC) was added in the 2002 farm bill.

Farm Bill Issues: Specialty crop producers were able to convince Congress to establish a separate ‘Horticulture’ farm bill title for programs dedicated to their interests, beginning in the 2008 farm bill. Programs currently included in that title are the Specialty Crop Block Grant Program ($72.5 million), resources ($62.5 million) to fund state efforts to monitor specialty crop pests and disease outbreaks and to set up “clean plant centers” that would provide pathogen-free propagative plant material to state agencies or private nurseries. The last major piece of the specialty crop pie was funding for specialty crop research ($80 million), which was included in the agricultural research title.

What to Watch: Specialty crop and livestock producers seem relatively satisfied with their current array of programs, and are not seeking major fixes to existing programs or to add new programs in the upcoming farm bill. Witnesses at a July 12 hearing on specialty crops held by the House Agriculture Committee largely reiterated their support for several of the key programs they obtained in earlier farm bills, such as the Technical Assistance for Specialty Crops (TASC) trade program and the Specialty Crop Block Grant program. They devoted much of their remaining written testimony to the issue of their sector’s need for improved access to immigrant labor under the H2-A temporary ag worker visa program, even though this issue is not under the Agriculture Committee’s jurisdiction.

Issues Summary: Nutrition Safety Net

Prepared by: Marianne Bitler, University of California, Davis; and Parke Wilde, Tufts University

Policy Setting: The House and Administration have recently proposed to block-grant the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or otherwise cut the program in various ways. SNAP and food distribution programs are authorized by the nutrition title of the Farm Bill. These programs have been central to the farm bill in at least 3 ways: they (a) accounted for approximately 80% of 2014 farm bill spending, (b) helped U.S. food producers by enhancing consumer demand, without generating corollary problems for trade agreements, environmental goals or other objectives, and (c) drew political support from non-farm legislators who provided much of the political muscle for passing the farm bill. SNAP participation and spending rose sharply during the Great Recession and were slow to decline in response to the economic recovery, but have been declining since 2014. SNAP has been shown to have positive effects on nutrition (e.g., Deb and Gregory, 2016).

Farm Bill Issues: Separating the nutrition title from the rest of the farm bill, converting SNAP from a mandatory program to a block grant for states, funding design changes, making nutrition improvements in SNAP, and instituting work requirements.

What to Watch: (1) Will nutrition be separated from the next farm bill? The House attempted such a separation in 2013, with the stated goal of reducing spending on food programs. (2) Will there be block grants, “flexibility” proposals, or requirements that states provide a share of non-administrative spending? Experience with block granting TANF include reduced countercyclical spending and less targeting of spending to the low-income population (Bitler and Hoynes, 2016). Requiring states to share in non-administrative spending would likely reduce total spending given their budget constraints. (3) Will new proposals merge to enhance SNAP nutrition impacts through incentives or restrictions? Recent research suggests extra SNAP benefits for buying fruits and vegetables increase their consumption (Bartlett et al., 2014), and incentives for healthy purchases and restrictions on unhealthy purchases improve nutritional quality (Harnack et al., 2016). A study of supplementary benefits found that restricting these benefits to items in the WIC package lowers redemptions but improves nutritional quality (Pindus et al., 2015). (4) Will work requirements or program parameters be changed to reduce cost? SNAP already disregards a share of earnings in determining income eligibility. The inability to relax work requirements during difficult economic times could have adverse effects. (5) How much funding will be provided for food distribution and smaller programs, which are important for some families (e.g., Pindus et al., 2016)?

Issues Summary: Environmental Services

Prepared by: Jonathan Coppess, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Policy Setting: Congress has pursued programmatic responses to low crop prices for more than eighty years but environmental services in the form of conservation programs were interspersed only periodically; conservation policies more often served the parity price support system by removing acres from production. With the landmark Food Security Act of 1985, conservation policy became a permanent component of farm bills, providing environmental services via rental payments to retire sensitive lands from production. It also combined conservation compliance on highly erodible lands and wetlands as a requirement for farmers to be eligible for Federal payments; a notable achievement during the farm economic crisis. Increasing environmental pressures and the advent of decoupled farm program payments subsequently pushed Congress to add working lands conservation policies designed to help offset the cost of conservation practices on farmland that remains in production. Historically, CRP acres have expanded during times of low crop prices.

Farm Bill Issues: The public perception of modern farming created by water quality hotspots such as the Great Lakes, Gulf of Mexico, Chesapeake Bay, and key drinking water sources for cities such as Des Moines is increasing pressure on elected officials, private food companies, and farmers to undertake greater efforts to address water quality concerns. Water quality degradation due to nutrient loss is particularly challenging for the existing suite of farm and conservation policies; predominantly a matter with productive farmland drained by subsurface tiles and fed by sufficient rains. Traditional conservation retirement programs are not suitable for such farmlands but working lands program funding has been too limited to adequately address the scope and scale of the problem. The two largest working lands programs (CSP and EQIP) enroll too few acres to match the scale and scope of the nutrient loss problem, as well as complicating factors such as 60% of all EQIP funds designated for livestock operations. USDA data indicate less than 35 million acres were under active contracts for the two programs in 2015, compared with nearly 283 million acres insured by crop insurance. Conservation compliance is applicable to farmland in production, however, it does little to assist farmers struggling to reduce nutrient losses at a time of lower crop prices.

What to Watch: The political environment for the pending farm bill debate will be challenging for conservation programs. Relatively lower crop prices and farm incomes will provide pressure to expand commodity assistance as well as CRP acres, which were limited to 24 million acres in the 2014 Farm Bill. Some environmental and conservation interests are also demanding an increase in CRP acres. The national average CRP rental rate per acre from 2008 to 2015 was over $57 per acre; adding 10 million acres to the cap could cost over $9 billion in the 10-year baseline at that average rental rate. More daunting, Congress will face pressure to reduce Federal outlays from mandatory programs; the 10-year spending estimates by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) will again play a key role. The demands to reduce nutrient loss, improve water quality and meet industry sustainability goals will add pressure on farmers with little assistance from expanding CRP.

Issues Summary: Rural Development

Prepared by Mary Ahearn, Consulting Economist and Retired ERS, USDA

Policy Setting: When the first farm bill was written, rural development was synonymous with agricultural development. Today, only about 6% of the nonmetropolitan (i.e., rural) population lives in counties economically dependent on farming. In fact, most farming households need a vibrant local nonfarm economy, as is evidenced by the dependence on off-farm income. While only about 14% of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, they had a significant impact on the results of the 2016 election (O’Brien and Ahearn, 2017). This has caused the national media–which does not customarily focus on rural issues–and numerous scholars to provide fuller reporting on the needs and motivations of rural residents. In general, indicators show a disadvantaged rural electorate (Kusmin 2016). We have seen the rural issue reflected in the single major legislative battle to date, i.e., the attempt to repeal health care, through concerns about its impact on underfunded rural hospitals and the services to rural residents suffering from opioid addiction. Another indicator of the sustained policy focus on rural issues post-election has been the President establishing an Interagency Taskforce on Agriculture and Rural Prosperity, first convened June 19. However, it is fair to say that the signals about investments in rural America have thus far been conflicting, as evidenced by the President’s budget. For example, the 2014 Farm Bill more than quadrupled the funds in the popular Value Added Producer Grant and made them mandatory, while the President’s Budget “zeroed out” its funding. In addition, USDA Secretary Perdue has replaced the Under Secretary for Rural Development position with an Assistant Secretary position, drawing strong bipartisan dissatisfaction from law makers on the Hill.

Farm Bill Issues: In the 2014 Farm Bill, the Rural Development Title VI accounted for only 22 of 356 pages and less than 1% of the budget. The 2014 Title VI extended most of the established programs (i.e., housing, utilities, and business/cooperatives); most of these programs have not historically been mandatory and are largely loan programs (Ahearn 2015). No potential investment has received as much discussion as investment in rural broadband. The private sector does not generally have incentives to invest in broadband infrastructure in remotely populated areas–where it is estimated that roughly 22 million are without broadband–thereby making public-private partnerships less viable. Public investment in broadband was included in the 2014 legislation (funds have also been provided via programs administered by Department of Commerce). Influential constituencies have been vocal about the need for continued investment in other infrastructure, including local water systems. Experts support the importance of investing in cooperatives, community and regional planning, as well as resources to encourage entrepreneurship, partnerships and outreach, but it is not clear how influential the constituents are for these outlays.

What to Watch: Given that the next Farm Bill will be written during the 2018 election season with the lessons from the 2016 elections still at the forefront, will lawmakers be inclined to protect and even expand traditional loan and grant programs, or will rural issues get lost in the larger SNAP-farm program debates and the pressure for budget cuts as reflected in the President’s budget? Will lawmakers embrace that rural economic development is more than support for agriculture? Will arguments, including those made by the current administration, for improved quality of life in rural areas through public and private investments lead to infrastructure investments–including human capital–and investments in rural broadband? Will the next Farm Bill require the Secretary to re-establish the Undersecretary for Rural Development, given the level of disappointment expressed on both sides of the aisle?

Issues Summary: Research and Extension

Prepared by: Constance Cullman, Farm Foundation

Policy Setting: Public funding has been credited as a foundation of U.S. agriculture. Since the signing of the Morrill Act in 1862, public support for research and extension has been a priority and most notably exists today in Title VII of the Agricultural Act of 2014. As discretionary programs, research funding lacks the protection enjoyed by mandatory programs and typically is not funded at fully authorized levels. Researchers and agricultural stakeholders contend that current funding and management systems are inadequate to meet today’s need to produce more with increasingly sustainable methods. Historically, support for research provisions in the Farm Bill have given way to demands for more assistance via the commodity and conservation titles. That may be changing. Increasingly, farm groups are moving research up the priority list and raising it as a priority concern to legislators. Support among legislators for research funding is typically bipartisan – a possible advantage in the current political climate.

Farm Bill Issues: Both House and Senate leaders have expressed clear recognition of the importance of agricultural research and its return on investment (Tomson). Most often viewed as yielding long-term results, research funding will, however, continue to vie for attention with the more tangible and immediate need for a workable safety net. In recent years, arguments for increased funding have failed (Clancy et al). Meanwhile legislators and agricultural stakeholders have taken note of the recent surge in Chinese public investment in agricultural research – a surge that has resulted in China surpassing the United States in public support (Clancy et al). This development may increase the President’s interest in research as perceived trade imbalances are addressed. Recently, mainstream farm groups such as the National Pork Producers Council have listed research and extension funding as a priority (NPPC) while Supporters of Agricultural Research have increased their efforts to highlight research needs (SoAR).

Despite support for various research programs including NIFA, AFRI (the President’s budget holds AFRI budget stable), FFAR, SCI, proponents are arguing for not just a surge in funding, but a new paradigm for agricultural research funding. Debate is likely to ensue regarding an improved system to improve USDA coordination, infrastructure and research priority setting, consolidation of existing programs (ARS, ERS, NIFA), and improved public-private collaboration arrangements. The success of FFAR to attract private funds, establish synergistic partnerships and quickly respond to immediate needs is being closely watched. Given FFAR’s limited track record, the current farm bill debate will likely focus on maintaining its original $200 million authorized in the 2014 Farm Bill.

What to Watch: (1) In an era of tight budgets, will/can Farm Bill efforts refocus from increased funding to seeking system changes? (2) Will traditional farm bill stakeholders ultimately place research as a top priority? (3) Will public-private collaboration systems, particularly FFAR, continue to receive support? (4) Can the public and private sectors better demonstrate an ability to collaborate? (5) Will land-grant institutions embrace a new paradigm? (6) Can a more impactful way be found to articulate the need for agricultural research to the public?

Prepared by: David Orden, Virginia Tech

Policy Setting: Since the 2016 election, trade policy has become a front-line policy issue. Farm groups are championing farm trade expansion as an opportunity for U.S. agriculture and the economy. The brief Trade Title III of the 2014 farm bill, with a relatively small projected 10-year budget ($3.6 billion), plays a role in expanding U.S. farm exports. However, it is not the main venue where policies affecting agricultural trade are determined. They include trade negotiations and accompanying legislation (e.g. proposed renegotiation of NAFTA), determination by countries of special tariffs such as antidumping duties, setting of phytosanitary and other product standards, and, within the farm bill, the commodity and crop insurance titles, to the extent that these titles affect production and are subject to WTO rules on domestic support.

Farm Bill Issues: Title III addresses expansion of U.S. exports along three basic lines. First, it sets guidelines for international food assistance programs administered by USDA and USAID. Restrictions that food aid commodities must be purchased domestically and shipped subject to “cargo preference” for American-flagged vessels have proven impervious to reform. Local and regional food procurement, more than two-thirds of global food aid, has been shown to reduce commodity costs; and shipping is more costly on the U.S. fleet. The 2014 farm bill provided USAID with slightly more operational flexibility at the margin and extended a small pilot USDA program for local/regional procurement (at $80 million/year). Also extended were efforts to improve the safety and quality of food aid. Reform advocates will continue to press for improving the cost effectiveness of these programs (Lentz and Barrett 2014).

Title III authorizes U.S. export credit guarantee programs. Competitors in world markets contend these programs are indirect export subsidies. The WTO agreed at its 2015 ministerial meeting to eliminate direct export subsidies in agriculture, but the U.S. deflected limits on programs viewed as potentially subsidizing exports indirectly. U.S. export credit programs were also an issue in the 2002 Brazil-U.S. WTO dispute on cotton support. The 2014 bill brought closure to this dispute by mutual agreement of the parties, which included eliminating prohibited subsidies and reducing the maximum length of U.S. short-term credit guarantees from 36 to 24 months.

Title III also authorizes the public-private partnership market development programs, MAP (Market Access Program) and FMD (Foreign Market Development). Public funds total about $230 million/year. Proponents argue these programs have had a high rate of return in expanding U.S. exports and point to rising private funding commitments as indicative of their success (Reimer et al. 2017). Critics see indirect export subsidies and ask, if as successful as proponents argue, why are public subsidies needed?

What to Watch: Both of the past two administrations sought more flexibility on food aid procurements and cargo preferences; further legislative efforts can be expected. Doings so would align U.S. food aid with international norms and enhance the humanitarian credibility of the United States, but such efforts are opposed by U.S. shippers. Monetization, where charitable delivery agencies sell aid commodities to cover their operating costs, has proven cost-inefficient; watch for additional efforts to constrain or eliminate this practice. Deficit hawks and agricultural interests will clash over MAP and FMD, while changes to the 2014 cotton program will precipitate international evaluation and scrutiny at the WTO.

Prepared by Scott Irwin, University of Illinois

Policy Setting: The general environment for energy policy has changed drastically since the 2014 Farm Bill was passed. Crude oil prices have fallen from over $100 per barrel to as low as $30. Gasoline prices at the pump have fallen to around $2 gallon. The reasons for the dramatic fall in prices include the unanticipated and large expansion of U.S. light tight oil (“fracking”) production and additional conventional production coming online in various places around the world, such as Iraq. One can summarize the setting as now one of relative “surplus” compared to “shortage” when the 2014 Farm Bill was being formulated. Another key change in the policy setting is the degree of emphasis on climate change mitigation. By withdrawing from the Paris Accords the Trump Administration has clearly signaled that this will not have nearly as high of priority as in the Obama Administration.

Farm Bill Issues: The energy title of the Farm Bill is relatively new, first appearing in the 2002 Bill. The main purpose of this title is to promote U.S. biofuels production and use, including corn ethanol, biodiesel, and cellulosic ethanol. The emphasis on type of biofuel has varied, with corn ethanol and biodiesel highlighted in 2002 and advanced (biodiesel and cellulosic) receiving central focus in 2008 and 2014. Total mandatory funding over the five years of the 2014 Farm Bill was $694 million, compared to $1.12 billion for the 2008 Farm Bill. Another $765 million of discretionary funding for the 2014 energy title was authorized.

The energy title created a number of programs, including: 1) Rural Energy for America Program (REAP) which provides grants and loan guarantees to ag producers, rural businesses, and electric cooperatives for energy efficiency and renewable energy related improvements; 2) Biomass Crop Assistance Program (BCAP) that supports the establishment and production of biomass for conversion to energy; 3) Biobased Markets Program which provides federal preference for purchase of biobased products; 4) Biorefinery, Renewable Chemical, and Biobased Product Manufacturing Assistance which provides loan guarantees for the development of advanced biofuel, renewable chemical, and biomanufacturing; 5) Repowering Assistance Program to provide funding for existing biorefineries to use biomass for heat and power; 6) Bioenergy Program for Advanced Biofuels to provide incentives for production of advanced biofuels excluding corn ethanol; 7) Biodiesel Fuel Education Program provides funding for biodiesel education; and 8) Biomass Research and Development that supports advanced research to improve bioenergy technology and production. Over half of the mandatory funds authorized as part of the 2014 energy title went to REAP and the Biorefinery, Renewable Chemical, and Biobased Product Manufacturing Assistance programs. A notable use of REAP in recent years was the much publicized funding for installation of blender pumps to help expand the use of higher ethanol blends such as E15 and E85.

What to Watch: In an environment of much lower crude oil and gasoline prices and less support from the Trump Administration for climate change mitigation, the energy title could be an easy target for budget cuts. In addition, there is the potential for some shifting of programs away from advanced biofuels, particularly cellulosic ethanol given the limited success in ramping up production, and moving support back towards corn ethanol. It would not be surprising to see corn ethanol interests push for further funding for programs to expand the infrastructure for higher ethanol blends in an effort to breach the E10 “blend wall.”

References

Ahearn, M.C. 2015. "Rural Development Title in the Farm Bill." Chapter 12 in Vincent H. Smith (ed.), The Economic Welfare and Trade Relations Implications of the 2014 Farm Bill. London: Emerald Publishing.

Bartlett, S., Klerman, J., Wilde, P. Olsho, L., Logan, C., Blocklin, M., Beauregard, M., Enver, A., Owens, C., and Melhem, M. 2014. Evaluation of the Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP) Final Report. Prepared by ABT Associates for USDA, FNS.

Bitler, M., and Hoynes, H.W. 2016. The more things change, the more they stay the same? The safety net and poverty in the Great Recession. Journal of Labor Economics; 34(S1): S403-S444.

Clancy, M, K. Fuglie, and P. Heisey. "U.S. Agricultural R&D in an Era of Falling Public Funding." Amber Waves (Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. November 10, 2016. Available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2016/november/us-agricultural-rd-in-an-era-of-falling-public-funding/.

Collins, A., Briefel, R., Klerman, J., Wolf, A. Rowe, G. Logan, C., Enver, A., Fatima, S., Gordon, Anne, and Lyskawa, J. 2015. Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children (SEBTC) demonstration: summary report. Prepared by Abt Associates and MPR for USDA, FNS.

Coppess, J. "Historical Background on the Conservation Reserve Program." farmdoc daily (7):82, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 4, 2017.

Coppess, J. 2016. "The Next Farm Bill May Present Opportunities for Hybrid Farm-Conservation Policies." Choices. Quarter 4. Available at http://www.choicesmagazine.org/ (and references listed therein).

Coppess, J., C. Zulauf, G. Schnitkey, and N. Paulson. "Reviewing the June 2017 CBO Baseline." farmdoc daily (7):127, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 14, 2017.

Deb, P., & Gregory, C. A. (2016). Who Benefits Most from SNAP? A Study of Food Security and Food Spending (No. w22977). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Good, K. "Budget, Appropriations Issues Continue to Unfold-Agriculture, Farm Bill." Farm Policy News. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics. July 21, 2017.

Harnack, L., Oakes, J.M., Elbe, B., Beatty, T., Rydell, S., and French, S. 2016. Effects of subsidies and prohibitions on nutrition in a food benefit program: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med; 176(11):1610-1618.

Hudson, D. 2017. "Keeping the Farm Safety Net for Cotton in "Proper" Perspective". SP17-07. http://www.depts.ttu.edu/aaec/icac/pubs/cotton/other_research_publications/orp_pdfs/SP1702.pdf.

Kusmin, L. 2016. "Rural America at a Glance, 2016 Edition." EIB No. 162. www.ers.usda.gov

Lentz, E. C. and C. Barrett. "The Negligible Welfare Effects of the International Food Aid Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill." Choices 3rd quarter, 2014.

Mercier, S. 2016. "Federal Benefits for Livestock and Specialty Crop Producers." Choices, 4th Quarter. Available online at: http://www.choicesmagazine.org/choices-magazine/theme-articles/looking-ahead-to-the-next-farm-bill/federal-benefits-for-livestock-and-specialty-crop-producers.

McMinimy, M.A. "Energy Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79): Status and Funding." Congressional Research Service, February 2016.

National Pork Producers Council. "NPP Farm Bill Priority: FMD Vaccine Bank." http://nppc.org/.

Novakovic, A. and C. Wolf. "Federal Interventions in Dairy Markets." Choices 31(December 2016). Available at http://www.choicesmagazine.org.

O'Brien, D.J. and M.C. Ahearn. 2017. "Rural Voice and Rural Investments: The 2016 Election and the Future of Rural Policy." Choices. Quarter 4 (2016). Available online: www.choicesmagazine.org

Pindus, N., Hafford, C., Levy, D., Biess, J., Simington, J., Hedman, C., and Smylie, J. 2016. Study of the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) final report. Prepared by Urban Institute for USDA, FNS.

Schnitkey, G. and C. Zulauf. 2016. "The Farm Safety Net for Field Crops." Choices. Quarter 4. Available online: http://www.choicesmagazine.org/choices-magazine/theme-articles/looking-ahead-to-the-next-farm-bill/the-farm-safety-net-for-field-crops.

Schnepf, R. "Renewable Energy Programs and the Farm Bill: Status and Issues." Congressional Research Service, October 2013.

Supporters of Agricultural Research Foundation. Retaking the Field: The Case for a Surge in Ag Research, Vol 1. Available at http://supportagresearch.org/retakingthefieldvol1/

Reimer, J., G. W. Williams, R. M. Dudensing and H. M. Kaiser. "Agricultural Export Promotion Programs Create Positive Economic Impacts." Choices 3rd quarter, 2017.

Tomson, Bill. "Lesson #7: Farm Bill supporter challenged to focus on the long-game of science." Agri-Pulse. https://www.agri-pulse.com/.

USDA Economic Research Service. Recent Costs and Returns: Cotton. 2017. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/commodity-costs-and-returns/commodity-costs-and-returns/.

Wilde, P. 2017. "The Nutrition Title's Long, Sometimes Strained, but Not Yet Broken, Marriage with the Farm Bill." Choices: The Magazine of Food, Farm, and Resource Issues. http://www.choicesmagazine.org.

Zulauf, Carl and David Orden. "80 Years of Farm Bills: Evolutionary Reform." Choices: Online Magazine. Included in article theme, "Looking Ahead to the Next Farm Bill." Agricultural and Applied Economics Association. 4th Quarter 2016. Available at http://www.choicesmagazine.org.

Zulauf, C., and G. Schnitkey. "Comparison and Assessment: Payments on Base vs. Planted Acres, 2014-2016 Crops." farmdoc daily (7):23, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. February 8, 2017.

Zulauf, C., G. Schnitkey, J. Coppess, and N. Paulson. "Farm Safety Net Support for Cotton in Perspective." farmdoc daily (7):87, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 11, 2017.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.