The Reconciliation Farm Bill: Is Conservation a Silver Lining?

Whether they know it or not, those grasping for optimism in dark times often turn to a concept first coined by the poet John Milton in 1634: the silver lining in a dark cloud (Milton, 1634; Keahey, March 22, 2021; etymonline.com, “silver lining”; Merriam-Webster, “silver lining”). As discussed at length, the Reconciliation Farm Bill made a series of problematic and concerning changes to farm support policy; all changes, however, were to farm subsidy and crop insurance policy designs (farmdoc daily, July 31, 2025; August 14, 2025; August 21, 2025; August 28, 2025; September 4, 2025). The Reconciliation Farm Bill also revised the funding for some of the conservation programs and this article approaches Milton’s “sable cloud” once more, this time in search of a possible silver lining.

Background

Section 10601 of the Reconciliation Farm Bill increased the budget authority for four of the major conservation programs: Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP); Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP); Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP); and the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) (P.L. 119-21). Unlike other farm assistance, the conservation funding increase was not paid for by cutting food assistance in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Instead, those funding increases were offset by eliminating the additional appropriated funds for those programs enacted in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (P.L. 117-169; farmdoc daily, November 7, 2024; October 10, 2024; Policy Design Lab, Issue Brief).

Discussion

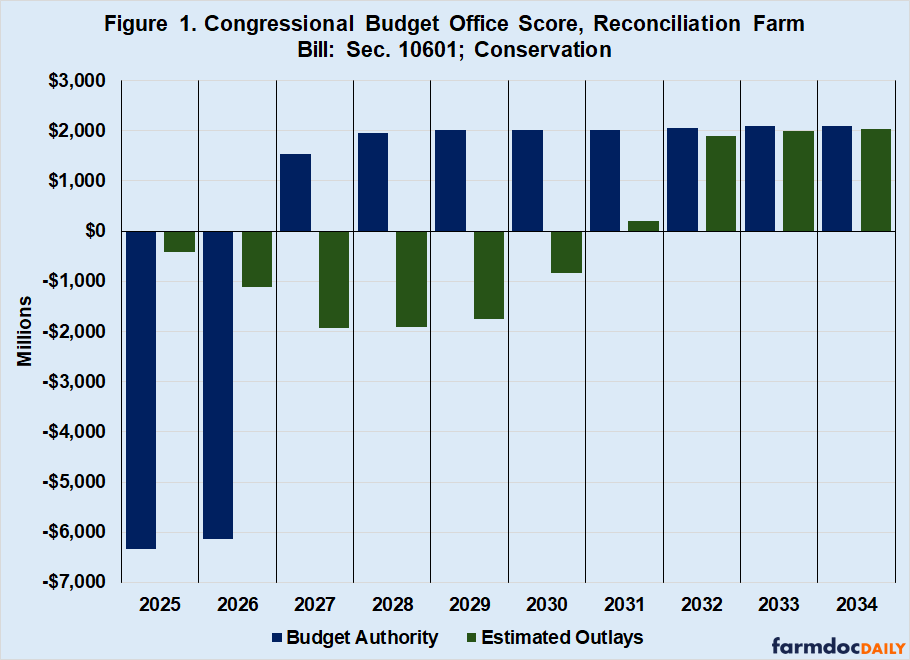

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) scored the Reconciliation Farm Bill’s changes to conservation policy as saving $1.8 billion over the ten years of the score (CBO, July 21, 2025). This is a bit of mathematical illusion due to the method of CBO scoring for conservation and the difference between budget authority (BA)—the amount Congress authorized—and outlays, the projected amount of that BA that CBO thinks will be spent based on historic spending rates. The January 2025 CBO baseline for these four (EQIP, CSP, ACEP, RCPP) conservation programs was $37.75 billion in BA (FY2026-2035) but slightly less, $37.257 billion, in outlays for those ten fiscal years (CBO, January 2025). The January baseline also projected $15.7 billion in remaining outlays (FY2026 to 2031) of the $18 billion appropriated by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA). Rescinding the IRA appropriation produced a reduction in outlays, which was used to increase the budget authority. Figure 1 illustrates the CBO score for the conservation provisions (Sec. 10601) of the Reconciliation Farm Bill. Note that the CBO score was for the ten fiscal years 2025 to 2034.

Figure 1 also illustrates the trade-off for these four conservation programs in the Reconciliation Farm Bill. In short, the increased but temporary funding available from the IRA was traded for permanent increases in budget authority that will spend more money over the longer term (but less in the near term). Through FY2034, CBO projects a net decrease in outlays of $1.8 billion but an increase in BA of $3.3 billion.

Expanding the BA window helps further demonstrate the tradeoff. Over 20 fiscal years (FY20265 to FY2045), the BA for these conservation programs increases by $38.8 billion from $75.5 billion to $114.3 billion. Figure 2 illustrates this more optimistic perspective of the conservation funding as revised by the Reconciliation Farm Bill. It combines the January 2025 baseline with the Reconciliation Farm Bill changes and projects them out through FY2045. Figure 2 also highlights the trade-off involved. The IRA outlays (blue dashed line) are much higher than the projected outlays from the Reconciliation Farm Bill, but only through FY2030. IRA funds were only available through FY2031, spending reverted to the baseline thereafter.

Over the longer time horizon, the Reconciliation Farm Bill is expected to provide more assistance to farmers for investing in conservation as compared to the IRA. The programs (and BA) are only authorized through FY2031, however. For those funds to actually help farmers after FY2031, Congress will have to reauthorize the budget authority without reductions. This tradeoff will only work for farmers seeking conservation assistance, therefore, if Congress does not eliminate or otherwise reduce the funding available and USDA is able to timely obligate the funds to farmers.

The conservation funding is only part of the picture, unfortunately. Figure 3 returns to the “sable cloud,” or more pessimistic, perspective. The increased BA for conservation is compared to the combined baseline for ARC/PLC and crop insurance, as well as the combined score from the Reconciliation Farm Bill. Baseline funding for these three programs exceeded that available to the four conservation programs. The more than $60 billion in additional funds projected for ARC, PLC and crop insurance dwarfs the increased BA for conservation programs. To the extent that those additional funds—especially the changes to crop insurance that encourage production of high-risk crops in high-risk areas—are contrary to conservation goals and the safeguarding of vital natural resources, the cloud darkens.

For conservation, however, there may be a much bigger concern. Inexplicably, Congress did not see fit to reauthorize the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) in the Reconciliation Farm Bill. The House did not include CRP in its version and the Byrd rule was not much of a barrier in the Senate (farmdoc daily, June 18, 2025). The authorization expires on September 30, 2025. The consequences of a failure to reauthorize this program may take time. USDA would not be able to hold any new signups, and new contracts would not be authorized. Existing contracts are expected to continue for the duration but when those contracts expire the acres enrolled will be available for a return to row crop production. To the extent those acres are poorly suited to farming, they raise significant risk for erosion and other natural resources, while any conservation benefits they provided will be lost along with the future rental payments. Figure 4 tracks the CRP contracts scheduled to expire between now and FY2031, as well as projects the lost rental benefits based on the data reported by the Farm Service Agency at USDA (USDA-FSA, “Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) Statistics”).

Created by Congress in the landmark Food Security Act of 1985, during the depths of the twin crises—economic and soil erosion—of the 1980s, CRP traces its roots to the Soil Bank in 1956 and the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act of 1936 during the Dust Bowl (Coppess, 2024). The nearly 26 million acres currently enrolled in CRP represent more than an acreage reserve. At roughly 8% of the total cropland used to produce crops (Winters-Michaud, December 30, 2024), CRP provides an agricultural monument to remind society of the consequences when farming exceeds nature’s limits and tolerance. We discard the program, and the lessons carried in the program’s acres, at our collective peril.

Concluding Thoughts

In the Reconciliation Farm Bill, Congress increased the budget authority for four conservation programs, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, Conservation Stewardship Program, Agricultural Conservation Easement Program, and Regional Conservation Partnership Program. Congress paid for these increases by rescinding the remaining funds appropriated by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 for those programs. This represents a tradeoff for conservation policy and those farmers seeking assistance to protect the natural resources under their control. A temporary but larger increase in conservation investments was traded for smaller increases in the short-term that will grow over time to a larger and potentially permanent increase in funding. That tradeoff will take many years to pay off and depends on future Congresses continuing the funding at the authorized levels and USDA’s ability to deliver those funds to the farmers seeking them.

In many ways, the conservation tradeoff offers a silver lining among the dark clouds of the rest of the Reconciliation Farm Bill. It was also the bare minimum Congress could have done for farmers, the environment, and the communities that are impacted by issues like erosion and water quality degradation. The tradeoff is certainly better than eliminating the funding. But a silver lining does not dissipate the dark clouds. The long-term potential increase in conservation funding is overshadowed by the likely damage contained in the increases to farm subsidy programs and the changes in crop insurance, the latter of which are likely to have vast consequences for natural resources such as soil and water when they incentivize through insurance production in the riskiest of areas. That shadow grows larger and more concerning when expiration of the Conservation Reserve Program is taken into account.

The silver lining also presents a larger message, a reminder of conservation policy’s seemingly unshakeable curse. Forced to try to achieve too much with too little funding and support, conservation outcomes are overly reliant on the heroic efforts of individual farmers and those that seek to help them. Perpetually underfunded for the demand from farmers, let alone the need, conservation policy throws pennies at massive challenges and expects miracles, often leaving the conservation farmer at a competitive disadvantage. Conservation policy also suffers from myriad design problems or flaws, including a failure to account for farm management and risk challenges that come with implementing conservation on a working farm. Combined, the insufficient funding and design problems diminish the silver lining.

A silver lining is little consolation under the shadow of dark clouds, but it can shed light. The Reconciliation Farm Bill’s bare minimum investment in conservation provides yet another reminder of lessons we as a society seem to have little interest in learning. For its entire existence, conservation policy has been treated as an afterthought in the political contests that unfold in Congress. This has had foreseeable consequences for its design and funding. Historically, natural resource issues gain the attention of policymakers only when vast and dire consequences like the Dust Bowl make it too difficult to ignore. One hopes that it won’t take another painful lesson to drive meaningful reform to policy, including sufficient investments in the natural resources upon which all of food and farming depend.

References

Congressional Budget Office. “Estimated Budgetary Effects of Public Law 119-21, to Provide for Reconciliation Pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Relative to CBO’s January 2025 Baseline.” Public Law 119-21 as enacted July 4, 2025. Cost Estimate. July 21, 2025. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61570.

Congressional Budget Office. “Details About Baseline Projections for Selected Programs: USDA Mandatory Farm Programs.” January 2025. https://www.cbo.gov/data/baseline-projections-selected-programs#23.

Coppess, Jonathan. Between Soil and Society: Legislative History and Political Development of Farm Bill Conservation Policy (University of Nebraska Press, 2024). https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/nebraska/9781496225146/between-soil-and-society/.

Coppess, J. "The Reconciliation Farm Bill: Top Five Most Problematic Changes to Farm Policy, #1." farmdoc daily (15):161, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 4, 2025.

Coppess, J. "The Reconciliation Farm Bill: Top Five Most Problematic Changes to Farm Policy, #2." farmdoc daily (15):157, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 28, 2025.

Coppess, J. "The Reconciliation Farm Bill: Top Five Most Problematic Changes to Farm Policy, #3." farmdoc daily (15):152, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 21, 2025.

Coppess, J. "The Reconciliation Farm Bill: Top Five Most Problematic Changes to Farm Policy, #4." farmdoc daily (15):147, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 14, 2025.

Coppess, J. "The Reconciliation Farm Bill: The Top Five Most Problematic Changes to Farm Policy, #5." farmdoc daily (15):139, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 31, 2025.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill in Reconciliation: What the Byrd Rule Exposes but Does Not Resolve." farmdoc daily (15):112, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 18, 2025.

Coppess, J. and Y. Peng. "Taking A Closer Look at the Conservation Tradeoff Issues." farmdoc daily (14):203, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, November 7, 2024.

Coppess, J. and Y. Peng. "Conservation Tradeoff: EQIP in the Inflation Reduction Act and the House Farm Bill." farmdoc daily (14):185, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, October 10, 2024.

Keahey, K. “Capturing the silver lining in infrastructure clouds.” Argonne National Library, Research Highlight. March 22, 2021.https://www.anl.gov/mcs/article/capturing-the-silver-lining-in-infrastructure-clouds.

Milton, J. “Comus: A Mask Presented at Ludlow Castle.” (1634). Available from, The John Milton Reading Room. Dartmouth College. https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/comus/text.shtml.

Winters-Michaud, C.P., Haro, A., Callahan, S. & Bigelow, D. (2024). Major Uses of Land in the United States, 2017. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-275.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.