Consumer Concerns about Tariffs and Food Prices

Introduction

Grocery prices play a large role in the public’s perceptions of inflation (e.g., Chua and Tsiaplias, 2024; Anesti, et al., 2024; D’Acunto, et al., 2021). At both grocery stores and gas pumps, consumers see price changes in real-time on a frequent basis, and these changes help inform their expectations about prices and inflation more broadly. While food inflation has continued to be top of mind for consumers over the last few years, tariffs have recently brought additional concern (e.g. Genovese, 2025; Hernandez, 2025; Leasca, 2025; Kaye, 2025; Creswell, 2025). This week, tariffs on goods imported from Mexico, Canada, and China went into effect, prompting concerns about price increases for consumers, slowed economic growth, and retaliatory tariffs (Palmer, 2025; Miller, et al., 2025; Lowder, et al., 2025).

In this post, we review results from the Gardner Food and Agricultural Policy Survey (GFAPS), which is conducted quarterly to evaluate public perceptions of important issues in food and agriculture. Here, we discuss public expectations for the impact of tariffs on food prices from the most recent wave (Wave 12, conducted in February 2025) and changes in tracked measures of public expectations about inflation.

In summary, we find that the majority of respondents across political parties expect tariffs to raise their food prices and are worried about the impact on their grocery bills. Additionally, we find that those who are worried about tariffs are also less optimistic about short-term inflation. Finally, we discuss tracked measures of inflation expectations, highlighting large partisan shifts in the last two waves.

Methods

The GFAPS is conducted quarterly using a national, online sample. Each quarter, approximately 1,000 U.S. adult consumers are recruited to match the population in terms of gender, age, region, and household income.

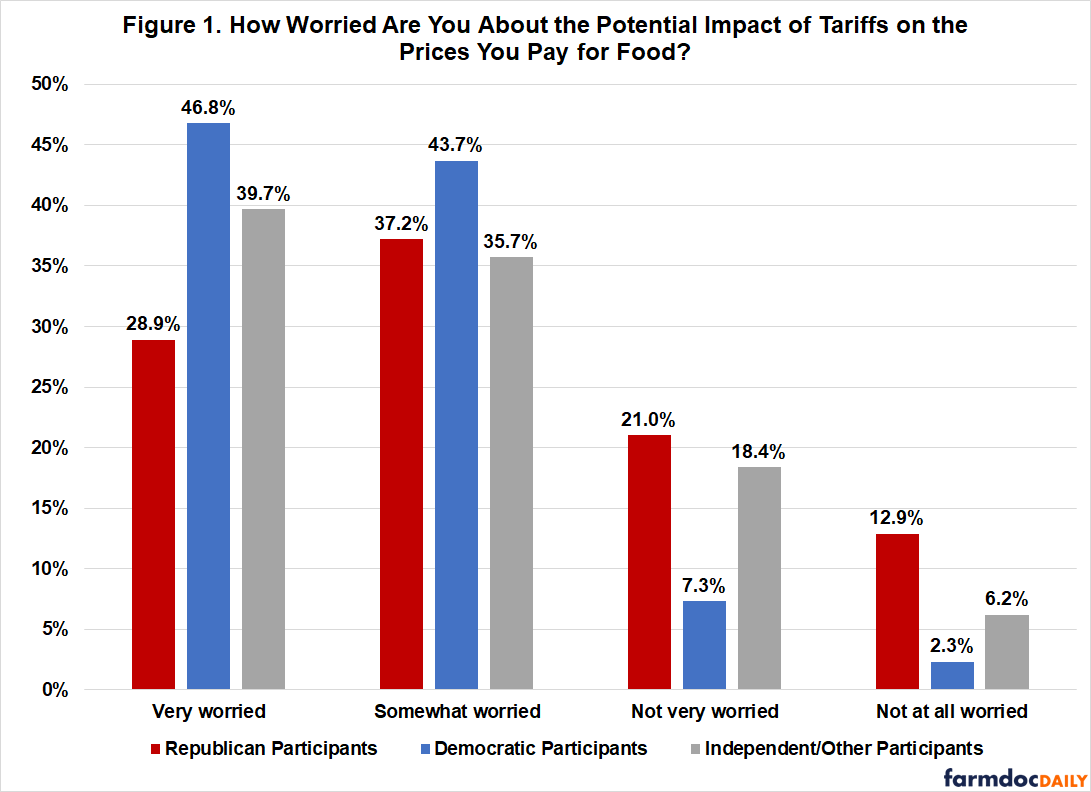

In this post we discuss results from the most recent wave (Wave 12) conducted in February 2025, which unpacks public perceptions of tariffs’ potential impacts on food prices. First, participants were asked, “If the U.S. implements tariffs on imported (non-U.S.) products, what do you expect the impact of these tariffs to be on the prices you pay for food?” We discuss the proportion who expected the tariffs to increase, have no effect, or decrease the prices they pay for food. Similarly, participants were asked, “How worried are you about the potential impact of tariffs on the prices you pay for food?” Participants could respond with one of four answers: very worried, somewhat worried, not very worried, or not at all worried. Finally, participants were asked if they had responded to potential tariffs through a variety of behavior changes. Specifically, participants were asked whether they had purchased larger amounts of items than they initially planned, purchased items earlier than they initially planned, and whether they had put off purchasing items they had originally planned to buy. We explore these results across participants’ stated political parties: Republican (n=395; 38.65%), Democratic (n=355; 34.74%), or Independent/Other (n=272; 26.61%).

Finally, we also review perceptions of inflation, which the GFAPS has tracked each quarter since November 2022 (Wave 3). Participants are asked, “In three months from now (May 2025), do you expect inflation to get worse, better, or stay about the same?” Each wave, the date is updated. Participants can respond with: much better, somewhat better, about the same, somewhat worse, or much worse. For analysis below, we evaluate the proportion of participants who responded somewhat worse or much worse in each wave.

Results

Public concerns about tariffs’ potential impacts on food prices

Results from the most recent wave of the GFAPS, conducted in February 2025, show that the public is quite concerned about the impact of potential tariffs on their grocery bills.

First, we asked about how participants would expect tariffs to impact their food prices. We find that the majority of participants across political parties indicated they expected food prices to increase. This was highest for Democratic participants (85.4% said they expected food prices to increase) but was also high for both Republican participants (74.6%) and Independent/Other participants (74.6%).

Second, we asked participants about how worried they were about the impact of tariffs on the prices they paid for food. We find that the majority of participants across political parties are either very worried or somewhat worried (see Figure 1). Higher levels of worry about the potential impacts of tariffs on the prices they pay for foods were more common for Democratic and Independent/Other participants than Republican participants, with 46.8% of Democratic participants, 39.7% of Independent/Other participants, and 28.9% of Republican participants indicating that they were very worried. Few indicated they were not at all worried, with 12.9% of Republican participants, 6.2% of Independent/Other participants, and just 2.3% of Democratic participants answering this way.

When asked about how they have been responding to potential tariffs, 38.6% of individuals indicated they had put off a purchase and 34.2% said they had purchased more of something than they had initially planned. For those who indicated they had responded to the potential tariffs by increasing the amounts of the items they purchased, we asked about what types of products they had stockpiled. The most common response was food or beverage (83.7% of those who stockpiled) or gasoline (50.6%). Both stockpiling and putting off purchases can have major implications for stakeholders in the food system.

Connections between tariffs and inflation?

Tariffs have the potential to increase the prices consumers pay for items, pushing up inflation. Table 1 shows the relationship between participants’ expectations for inflation in the next three months and their level of worry about the impact of potential tariffs on the prices they pay for food, using results from the most recent wave of the GFAPS.

We find that consumers seem to be making the connection between tariffs and their expectations for inflation. The interaction between these two measures results highlights that those who are concerned about tariffs’ impacts on their food prices are also less optimistic about inflation in the coming months, whereas those who are not worried about tariffs’ impacts are also more optimistic about inflation. Specifically, our results show that for participants who are either somewhat or very worried about tariffs (n=788), 42.5% expect inflation to worsen in the next three months, 26.5% expect it to stay approximately the same, and 31.0% expect it to improve. For participants who are not worried about tariffs (n=235), only 9.8% expect inflation to worsen in the next three months, 37.9% expect it to stay approximately the same, and 52.3% expect it to improve.

Table 1. The Proportion of Participants Who Are Worried or Not Worried About the Impact of Tariffs Who Expect Inflation to Get Better, Stay the Same, or Get Worse in the Next Three Months

| Participants’ level of worry about potential tariffs’ impacts on the prices they pay for food | ||

| Expectation for inflation in the next three months | Worried (n=788) |

Not Worried (n=235) |

| Better | 31.0% | 52.3% |

| Same | 26.5% | 37.9% |

| Worse | 42.5% | 9.8% |

Our findings show that consumers are concerned about the impact of tariffs on food prices. These results echo other work, which has found that the public expects tariffs to raise prices for goods they buy more broadly (e.g., Good, 2025; Balagtas and Bryant, 2025; Zhang and Igielnik, 2025) and that tariffs brought increased inflationary concerns to many along the supply chain (e.g., Mutikani, 2025; Tyson, 2025; Coibion, et al., 2025).

Public concerns about inflation and food prices

Results from 10 waves of GFAPS – from November 2022 to February 2025 – highlight that participants’ expectations about inflation have exhibited large shifts. Figure 2 shows the proportion of Republican participants (red line), Democratic participants (blue line), and Independent/Other participants (gray line) who indicated they expected inflation to worsen in the next three months across waves. Thus, for example, results from this wave (Wave 12, February 2025) reflect participants’ expectations about inflation in May 2025. Expectations about inflation shifted in wave 11 (November 2024, conducted in the days after the election) and wave 12 (February 2025, conducted weeks after inauguration), seeming to coincide with the change in administration.

We find that Republicans became much more optimistic following the election, with a 29-percentage point drop from Wave 10 (August 2024), when 43.2% of Republican participants indicating they expected inflation to worsen versus Wave 11 (November 2024) when just 14.0% thought inflation would worsen in the next three months. Republican participants have remained more optimistic in the most recent wave (February 2025), with only 14.9% indicating they expect inflation to worsen.

Democrats became somewhat more pessimistic following the election, increasing 5.9 percentage points from 26.2% who expected inflation to worsen in Wave 10 to 32.1% who expected inflation to worsen in Wave 11. However, Democrats became much more pessimistic in the latest wave, with 51.8% of Democrats now indicating they expect inflation to worsen in the next three months.

As for Independents/Other participants, this group became more optimistic following the election, with a 12.2 percentage point jump from 38.9% who expected inflation to worsen in Wave 10 to just 26.7% who expected inflation to worsen when asked in Wave 11. However, Independent/Other participants became more pessimistic in the most recent wave, returning to near the group’s average with 42.3% of participants expecting inflation to worsen in the next three months.

Partisan perspectives surrounding inflation and economic well-being have been well documented across multiple administration changes – with those whose candidate loses feeling more pessimistic and those whose candidate wins feeling more optimistic – and previous work has highlighted that this gap has grown (e.g., Hsu, 2024).

Conclusions

Grocery stores and gas pumps play an important role in informing consumers’ economic expectations and perceptions of inflation. The impacts are felt in real time, directly, and frequently. While inflationary concerns have been persistent in recent years, this week’s tariffs on key trading partners (Canada, Mexico, and China) have prompted addition concern about prices.

Results from the Gardner Food and Agricultural Policy Survey find that the majority of consumers – across parties – expect tariffs to increase the prices they pay for food. This was highest for Democratic participants (85.4% said they expected food prices to increase) but was also very high for both Republican participants (74.6%) and Independent/Other participants (74.6%).

Similarly, our results show that consumers are bracing for the impact. Just over 77% of participants responded that they are either somewhat or very worried about tariffs, and those who are worried about tariffs’ impacts on food prices are also pessimistic about short-term inflation, expecting inflation to worsen in the next few months.

Finally, we review tracked measures of short-term inflation expectations, highlighting substantial partisan changes across time. Our results show that Republican participants became more optimistic following the election and stayed optimistic in the most recent wave (conducted in February 2025), Democrat participants became somewhat more pessimistic in November and much more pessimistic in the most recent wave, and Independent/Other participants became more optimistic in November but dropped back to pre-election expectations in the most recent wave.

Consumers’ expectations for the economy and inflation have important implications for stakeholders all along the food system. With tariffs now a reality, the Gardner Food and Agricultural Policy Survey will continue to track consumer perceptions and views, adding to a running record soon approaching three years.

References

Anesti, N., Esady, V., and Naylor, M. (2024). “Food prices matter most: Sensitive household inflation expectations.” Working paper.

Balagtas, J. and Bryant, E. (2025). Consumer Food Insights – Purdue University. https://ag.purdue.edu/cfdas/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Report_202501.pdf

Chua, C. L. and Tsiaplias, S. (2024). “The influence of supermarket prices on consumer inflation expectations.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 219: pp. 214-233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2024.01.022

Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., and Weber, M. (2025). “The Upcoming Trump Tariffs: What Americans Expect and How They Are Responding.” Working Paper.

Creswell, J. (2025). “Tariffs Add a New Shock to Food Supply Chains.” The New York Times. March 5, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/05/business/tariffs-food-supply-chains.html

D’Acunto, F., Malmendier, U., Ospina, J., and Weber, M. (2021). “Exposure to Grocery Prices and Inflation Expectations.” Journal of Political Economy. 129(5). https://doi.org/10.1086/713192

Genovese, D. (2025). “How Trump's tariffs could affect the price of popular foods.” Fox Business. February 3, 2025. https://www.foxbusiness.com/economy/how-trumps-tariffs-could-affect-price-popular-foods

Good, C. (2025). “Americans are bracing for tariffs. Here’s what businesses need to know.” IPSOS. January 21, 2025. https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/americans-are-bracing-tariffs-heres-what-businesses-need-know

Hernandez, J. (2025). “How Trump's tariffs on steel and aluminum could hit you at the grocery store.” NPR. February 20, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/02/20/nx-s1-5300051/tariffs-steel-aluminum-cans-food-groceries

Hsu, J. (2024). “Partisan Perceptions and Expectations.” Surveys of Consumers – University of Michigan. February 23, 2024. https://data.sca.isr.umich.edu/fetchdoc.php?docid=75088

Kaye, D. (2025). “From Groceries to Cars, Tariffs Could Raise Prices for U.S. Consumers.” The New York Times. March 4, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/article/trump-tariffs-prices-consumers.html

Leasca, S. (2025). “These Foods Will Likely Get More Expensive After Trump's Tariffs Take Effect.” Food & Wine. February 3, 2025. https://www.foodandwine.com/trump-tariffs-food-grocery-prices-8784509

Lowder, D., Shalal, A., and Holland, S. (2025). “Trump locks in Canada, Mexico tariffs to launch on Tuesday; stocks tumble.” Reuters. March 3, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/trump-decide-us-tariff-levels-mexico-canada-tuesday-deadline-approaches-2025-03-03/

Miller, Z., Boak, J., and Gillies, R. (2025). “Trump says 25% tariffs on Mexican and Canadian imports will start Tuesday, with ‘no room’ for delay.” AP News. March 3, 2025. https://apnews.com/article/trump-tariffs-mexico-canada-b19e004dddb579c373b247037e04424b

Mutikani, L. (2025). US consumer inflation expectations soar in January on tariff fears. Reuters. January 10, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/us-consumer-inflation-expectations-soar-january-tariff-fears-2025-01-10/

Palmer, D. (2025). “‘No room left’ for a deal: Trump says Canada, Mexico tariffs take effect Tuesday.” Politico. March 3, 2025. https://www.politico.com/news/2025/03/03/lutnick-trump-canada-mexico-tariffs-00207238

Tyson, J. (2025). “Trump tariffs to stoke inflation in 2025: corporate economists.” CFO Dive. February 10, 2025. https://www.cfodive.com/news/trump-tariffs-stoke-inflation-2025-corporate-economists-trade/739740/

Zhang C. and Igielnik, R. (2025). “How Americans Feel About Tariffs.” The New York Times. March 4, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/03/04/polls/tariffs-trump-poll.html

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.