On the Origins of Budget Reconciliation

Reconciling reconciliation: trying to understand the process whilst attempting to evaluate its potential impacts. Congress is working to advance a budget reconciliation process that may require cutting at least $230 billion from the Farm Bill baseline. The complicated undertaking will likely consume the legislative calendar for the foreseeable future (see e.g., Penn Wharton Budget Model, February 27, 2025; Carney et al., February 26, 2025; McCarthy, Kashinsky and Carney, February 26, 2025; Bogage and Sotomayor, February 25, 2025; Sanger-Katz and Parlapiaon, February 25, 2025; Scholtes and Tully-McManus, February 25, 2025; Sprunt, February 25, 2025; Bipartisan Policy Center, August 28, 2024; farmdoc daily, November 21, 2024). Many of the biggest questions raised by reconciliation have few answers and would extend beyond the scope of this article anyway. Maybe history offers handholds in the turbulent times, helping develop an understanding of the path that led to them. To that end, this article reviews the origin story of the budget reconciliation process.

Background

As one of his last acts as President before resigning, Richard Nixon signed the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 into law on July 12, 1974 (P.L. 93-344). Buried in Title III of the legislation, as part of the Congressional budget process, Congress created a process for budget reconciliation. It was initially designed to be part of the second annual budget resolution (completed by September 25th each year), reconciling the outcomes during the fiscal year to the initial budget resolution (May 15th deadline each year) and goals for spending and revenue. Congress also included a provision in Section 301(b)(2) that the first concurrent resolution may contain “additional matters” including “any other procedure which is considered appropriate to carry out the purposes of this Act” (P.L. 93-344). The managers of the conference clarified, however, that this section was to apply “only to the specific procedures for the enactment of budget authority and spending authority legislation for the coming fiscal year and not to the jurisdiction of committees, the authorization of budget authority, or to permanent changes in congressional procedure” (S. Rept. 93-924, at 58; H. Rept. 93-1101, at 58).

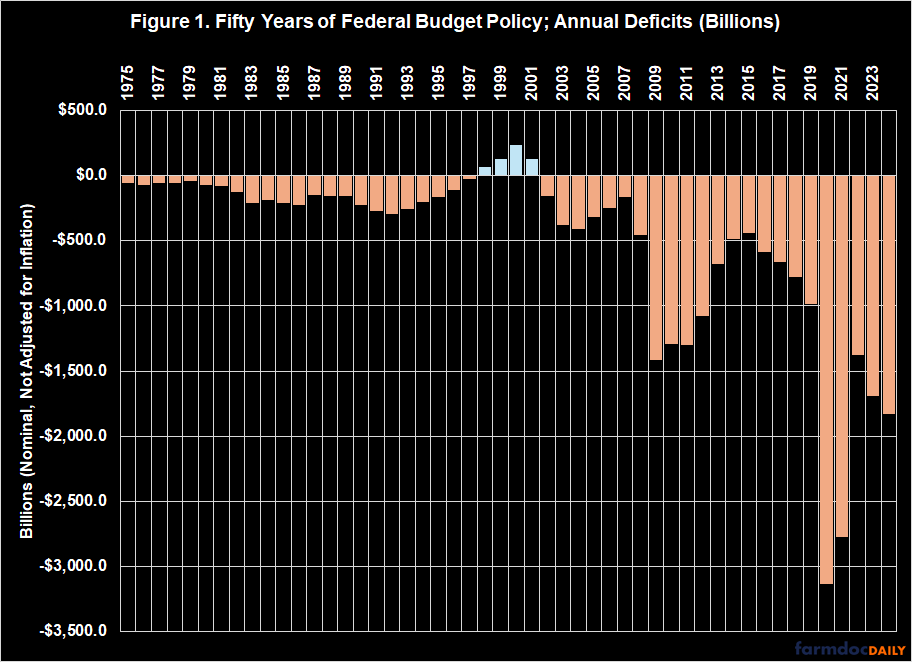

Figure 1 provides an opening perspective on federal budget policy. Budget policy has developed over the course of fifty years, but largely in a single direction focused on reducing federal spending and programs. Figure 1 illustrates the annual deficits or surpluses (revenues minus spending or outlays) from 1975 to 2024 as reported by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO, January 2025).

The results of 50 years of budget policy do not look much like success. Since 1974, there have been only four years, 1997 to 2001, in which the government experienced a surplus. Each fiscal year of deficits adds to the total federal debt.

Discussion

In writing what became the 1974 Act, both the House and Senate included provisions for a reconciliation process, including an intent that reconciliation apply to entitlement program spending as well as appropriations. Senator Sam Ervin (D-NC) was chairman of the Senate Committee on Government Operations that authored the 1974 Act. In December 1974, he wrote in the preface of a legislative history of that the Act compiled by his staff that the bill was “the single most important piece of legislation enacted” during his 20 years in the Senate (U.S. Senate, 1974). Scholars of Congress have reached a similar conclusion that the 1974 Act “was the most significant congressional reform of the 1970s, which was itself the most reform-minded decade in more than half a century” (Fenno, 1991).

Put simply, reconciliation today is not reconciliation as it was designed. The reconciliation instructions in the current Congressional budget resolutions are for the first (and likely only) budget resolution, rather than the second budget resolution as a method for reconciling fiscal matters towards the end of the fiscal year. This fundamental change happened in three steps, and was the product of a failure of the process as designed.

The first reconciliation instruction was by the Senate in 1977 and was included in the second budget resolution for FY1978 (S. Rept. 95-399; U.S. House, Serial No. CP-9, October 1984). The instruction, notably, was to the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry to reduce outlays by $4.1 billion. The instruction was removed in debate on the Senate floor, however.

In 1979, the Senate attempted to include a reconciliation instruction in the second budget resolution, this time to six Senate and seven House authorizing committees to reduce outlays by nearly $2 billion. The House did not include reconciliation instructions in its second budget resolution and resisted them in the conference negotiations with the Senate. Without agreement in conference, the House removed the reconciliation language during consideration of the conference product. Republicans in the House fought against the effort to drop reconciliation, but it passed the House by a vote of 205 to 190 (38 not voting) in early November, sending that revised conference report to the Senate for reconsideration (Congressional Record, November 8, 1979, at 31494).

House Budget Committee chairman Robert Giaimo (D-CT) argued that a special effort was being led by Representative Leon Panetta (D-CA) to produce legislative reforms that would reduce spending by $3 billion. That effort, he argued, was making progress and reconciliation instructions would derail it. Reconciliation was also being attempted too late in the year and would be too cumbersome at that late date (Id., at 31470). Republicans were unhappy with the move. Representative Delbert Latta (R-OH), the Ranking Member of the House Budget Committee, argued that removing the reconciliation instruction would render the budget process “useless” while freshman Representative Newt Gingrich (R-GA) argued that the move would “destroy the very budget system” (Id., at 31476 and 31491, respectively). Disagreement between the House and Senate continued, requiring Congress to try again in late November. In the revised resolution, reconciliation was reduced to a Sense of Congress that the listed committees should complete their work to reduce spending in their jurisdiction. Both chambers agreed to it, the House by a vote of 206 to 186 (41 not voting) (see, Congressional Record, November 28, 1979, at 33915).

The third step in its early development was the most critical one. The 1979 dispute over reconciliation carried over into the next year. An election year, 1980 opened with the Budget Committees including reconciliation instructions in the first budget resolution for FY1981, rather than the second resolution (H. Con. Res. 307; H. Rept. 96-857; S. Con. Res. 86; S. Rept. 96-654; Schick, 1981). The Senate sought to achieve a balanced budget while also enacting a $10 billion tax cut and instructed ten committees to reduce spending by $12 billion in FY1980 and FY1981, as well as more than $85 billion over the following five fiscal years (S. Rept. 96-654, at 245). Reconciliation included a $2 billion reduction by the Agriculture Committees. The House budget included instructions to eight House committees to reduce spending by over $9 billion in FY1981, including over $500 million from Agriculture (H. Rept. 96-857, at 13-14). The House Budget Committee acknowledged that it was implementing an “extraordinary procedure” but deemed it necessary to “balance the budget” when “there may not be time to act on reconciliation instructions” in an election year (Id.).

The House budget’s reconciliation instruction was met with opposition on the House floor, led by Representative Morris Udall (D-AZ). In March, Udall and 15 other committee chairs sent a letter to Speaker of the House O’Neil opposing inclusion of reconciliation instructions in the first resolution because, in part, it undercut the committee system and would damage the legislative process (Congressional Record, May 7, 1980, at 10153). The House rejected Udall’s amendment to strike the reconciliation instructions by a vote of 127 to 289 (16 not voting) on May 7, 1980 (Id., at 10183). Udall argued that inclusion of the instruction violated the “solemn decision” made by Congress in the 1974 Act and called it an “attack on the committee system” that transferred power to the Budget Committee (Id., at 10152-53). House Budget chairman Giaimo and Representative Panetta pushed back, calling it essential for the budget and for reducing spending; Ranking Member of the Budget Committee Latta pointed to the failure in November 1979 as proof that moving reconciliation to the first resolution was the only way to force Congress to cut spending (Id., at 10154-59). Overwhelmed by concerns about inflation in a difficult election year, Congress eventually agreed to reconciliation and produced the first omnibus reconciliation bill in September, but the conference agreement on reconciliation legislation was not completed until December, signed into law by a lame duck President Jimmy Carter on December 5, 1980 (P.L. 96-499; U.S. House, Serial No. CP-9, October 1984; Schick, 1981). Of note, it included cuts to the School Lunch and Child Nutrition Programs.

Concluding Thoughts

The minutia and mundane of procedure obscure the power to initiate vast, far-reaching change, a catalyst often the result of failure. Moving reconciliation to the first budget resolution in 1980 became the precedent for the massive 1981 reconciliation effort. The latter was much larger and included instructions to cut spending, including from entitlement programs, in multiple years beyond the budget year. That effort pushed through President Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts and budget priorities, led by his Director of the Office of Management and Budget, David Stockman (Schick, 1981; Miller and Range, 1983; Otton, 1983). As one scholar noted, “[h]ad the Democrats not inaugurated reconciliation by shifting it to the first resolution, it would not have been available for Stockman in 1981” (Gilmour, 1990; at 111-12).

Reconciliation in 1981 became the precedent for future reconciliation efforts including the current efforts in the 119th Congress. The warnings sounded in 1980 carry a modicum of prescience into the present, although they remain somewhat muffled by the obvious self-interest of the committee chairs who fought against the change. Reconciliation has changed Congressional budgeting and, through it, the legislative process; it has not, however, changed the trajectory of federal deficits and debt. Reconciliation is the ultimate negative-sum effort, pitting interests against each other and amplifying partisanship in a contest to inflict damage on certain priorities (Wildavsky 1988, Davis, October 15, 2017). The omnibus and expedited nature of the procedure favors “powerful clients with weak claims” contrary to Stockman’s stated formulation of the ideal (Stockman, quoted in Greider, 1981). Clients or constituents that are weak because they are numerous and disorganized, are weakened further by a process narrowed to considering only spending reductions—small benefits to large constituencies spend much more in the aggregate budget figures than do large benefits to small constituencies. The consequences are felt far and wide. The pending reconciliation of the current Congress is expected to prove the rule yet again.

References

Bipartisan Policy Center. “Budget Reconciliation, Simplified.” August 28, 2024. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/explainer/budget-reconciliation-simplified/.

Bogage, Jacob and Marianna Sotomayor. “House narrowly passes GOP’s ‘big, beautiful bill’ for Trump’s agenda.” The Washington Post. February 25, 2025. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2025/02/25/johnson-reconciliation-trump/.

Carney, Jordain, Katherine Tully-McManus and Benjamin Guggenheim. “Senate Republicans say House budget won’t fly with them.” Politico.com. February 26, 2025. https://www.politico.com/news/2025/02/26/senate-republicans-reject-house-budget-00206244.

Coppess, J. "Reauthorization or Reconciliation: Thoughts on the Farm Bill’s Prospects." farmdoc daily (14):213, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, November 21, 2024. https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2024/11/reauthorization-or-reconciliation-thoughts-on-the-farm-bills-prospects.html.

Davis, Jeff. “The Rule that Broke the Senate.” Politico.com. October 15, 2017. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/10/15/how-budget-reconciliation-broke-congress-215706/.

Fenno, Richard F., Jr. The Emergence of a Senate Leader: Pete Domenici and the Reagan Budget (Washington DC: CQ Press, 1991).

Gilmour, John B. Reconcilable Differences?: Congress, the Budget Process, and the Deficit. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1t1nb1cw/.

McCarthy, Mia, Lisa Kashinsky, and Jordain Carney. “Capitol agenda: What's next for Johnson's budget resolution.” Politico.com. February 26, 2025. https://www.politico.com/live-updates/2025/02/26/congress/johnson-budget-senate-changes-00206158.

Miller, James A., and James D. Range. “Reconciling an Irreconcilable Budget: The New Politics of the Budget Process.” Harv. J. on Legis. 20 (1983): 4.

Penn Wharton Budget Model. “The FY2025 House Budget reconciliation and Trump Administration Tax Proposals: Budgetary, Economic, and Distributional Effects.” University of Pennsylvania. February 27, 2025. https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2025/2/27/fy2025-house-budget-reconciliation-and-trump-tax-proposals-effects.

Otte, George. “Braking the Federal Budget: The Emergence of Reconciliation in Budget Policy.” In Pub. L. Forum, vol. 3, p. 155. 1983.

Sanger-Katz, Margot and Alicia Parlapiano. “What Can House Republicans Cut Instead of Medicaid? Not Much.” The New York Times. February 25, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/25/upshot/republicans-medicaid-house-budget.html.

Schick, Allen. Reconciliation and the Congressional Budget Process. (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, Study in Political and Social Processes 1981). https://www.jstor.org/stable/418698.

Scholtes, Jennifer and Katherine Tully-McManus. “Republican leaders seek ‘united’ GOP funding strategy as shutdown looms.” Politico.com. February 25, 2025. https://www.politico.com/live-updates/2025/02/25/congress/republican-leaders-seek-united-gop-funding-strategy-as-shutdown-looms-00206154.

Sprunt, Barbara. “Reconciliation is the key to unlocking Trump's agenda. Here's how it works.” NPR.com. February 25, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/02/25/g-s1-50474/reconciliation-trump-republicans-congress.

U.S. House of Representatives. Committee of Conference. “Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974.” H. Rept. 93-1101 (93rd Congress, 2d Session; June 11, 1974).

U.S. House of Representatives. Committee on the Budget. “First Concurrent Resolution on the Budget—Fiscal Year 1981.” H. Rept. 96-857, H. Con. Res. 307 (96th Congress, 2d Session; March 26, 1980).

U.S. House of Representatives. Committee on the Budget. “A Review of the Reconciliation Process.” Serial No. CP-9 (98th Congress, 2d Session; October 1984).

U.S. Senate. Committee of Conference. “Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974.” S. Rept. 93-924 (93rd Congress, 2d Session; June 12, 1974).

U.S. Senate. Committee on Government Operations. “Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974: Legislative History.” (93rd Congress, 2d Session; December 1974).

U.S. Senate. Committee on the Budget. “Second Concurrent Resolution on the Budget, FY1978.” S. Rept. 95-399 to accompany S. Con. Res. 43 (95th Congress, 1st Session; August 1977).

U.S. Senate. Committee on the Budget. “First Concurrent Resolution on the Budget FY1981.” S. Rept. 96-654 to accompany S. Con. Res. 86 (96th Congress, 2d Session; April 9, 1980).

Wildavsky, Aaron. The New Politics of the Budgetary Process (Glenview: Scott, Foresman, 1988).

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.