Farm Bill 2023: NRCS Backlogs and the Conservation Bardo

A shutdown of the government of the United States of America is upon us. It is an outcome that almost no one seems to want—including all but a very small minority of those elected by the people to govern—and yet the leadership of the House of Representatives cannot muster the political will to avoid it. The federal fiscal year ends at midnight on Saturday, September 30th (Carney and Beavers, September 27, 2023; Everett, September 27, 2023; Bogage and Sotomayor, September 27, 2023; Alfaro et al., September 26, 2023; Everett et al., September 26, 2023). The pointless spectacle of a government shutdown presents a vast array of problems and consequences, as well as costs. It exemplifies a tyranny of the minority, but it is not the only example (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2023). Among the consequences are further delays in, or roadblocks to, reauthorization of a farm bill. If there is a silver lining for the farm bill, it may be that the pause could allow for further reflection on the state of negotiations and a chance to reset or recalibrate. To that end, a recent news release from USDA provided a catalyst for the discussion that follows. Recently, USDA provided an update on the conservation spending provided by Congress in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (USDA, September 19, 2023). Arguably most notable in this release was the substantial demand for conservation assistance and Inflation Reduction Act funding from farmers: for all four programs, demand exceeded the funding available. This is an all-too-common issue for conservation programs and funding, and is explored further in this article.

Background

Begin with an admission: as used here, bardo is a borrowed term used for illustrative purposes. The term comes from Tibetan or Buddhist concepts about a transitional purgatory realm or state, such as between rebirths or between life and death. It is, in other words, a state of limbo where one can become stuck or trapped. Maybe the most prominent example of recent usage was in the 2017 novel Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders. The bardo, then, may best be understood as “[s]omewhere between life and death, it is a transitory place where those who cannot move on to the afterlife dwell” (Hiltrop and Polak, 2022; see also, Saunders, March 4, 2017; Whitehead, February 9, 2017). With no disrespect intended, the concept of the bardo is borrowed here to illustrate a significant problem for conservation policies and programs. The conservation bardo exists for farmers that become stuck in the process: they have applied for conservation assistance; their application has been approved by USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS); but they are unable to receive the conservation assistance because the funds are not available. This is the conservation bardo, which is also known as the NRCS backlog.

The conservation bardo is largely the result of a specific design applicable only to these programs. Congress has placed either a cap or limit on the funding available, or Congress has limited the acres that may be enrolled. The Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) is the primary example of the former: in the statute, Congress has provided up to $2.025 billion each fiscal year (FY) for the program spending (16 U.S.C. §3841). The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) is an example of the latter: in the statute Congress has limited the total acres that can be enrolled to 27 million acres in FY 2023 (16 U.S.C. §3831). The Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) provides an important example of both. In the 2002, 2008, and 2014 Farm Bills the program was based on acres enrolled; the 2014 Farm Bill, for example, required USDA to enroll an additional 10 million acres each fiscal year (P.L. 113-79). Notably, this was a reduction from the requirement for enrollment of an additional 12.769 million acres each FY required by the 2008 Farm Bill (P.L. 110-246). The 2018 Farm Bill changed the program from an acreage-based program to a fixed funding allocation that increased to $1 billion per FY (P.L. 115-334).

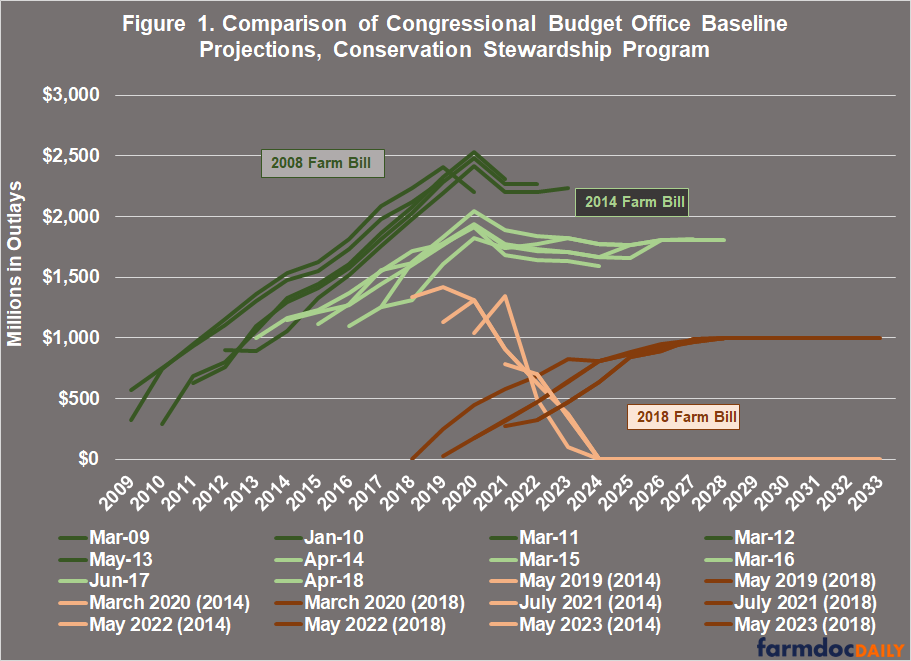

The discussion below will focus on EQIP, but CSP is worth a further quick look. Figure 1 compares each Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline projection for CSP back to the 2009 baseline after the 2008 Farm Bill. The baselines for CSP from the 2008 Farm Bill are in dark green, those for the 2014 Farm Bill are in light green, and those for the 2018 Farm Bill are split between the 2014 version of CSP which fades out (light pink) and the 2018 version of CSP (dark pink). From Figure 1, the shift in spending expectations for CSP when it was based on acres to spending expectations for CSP at a fixed amount of funding are substantial.

It is also notable (but not illustrated in Figure 1) that the 2018 version of CSP not only has much lower projections than both acreage versions of the program, but the CBO data consistently projects outlays below the budget authority provided by Congress in the statute. For example, in the May 2023 baseline, CBO reports actual outlays of $324 million on budget authority of $800 million (40.5% of available funds) and the projections for outlays do not equal the total amounts made available by Congress until FY2028. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provided additional funding for CSP, as well as for EQIP, but as USDA reported the demand continues to outpace available funds by a significant amount. This raises substantial questions about the impact of fixed funding amounts on the operation of these programs, as discussed below for EQIP, but this initial look at CSP more than begs for further analysis for that program as well.

Discussion

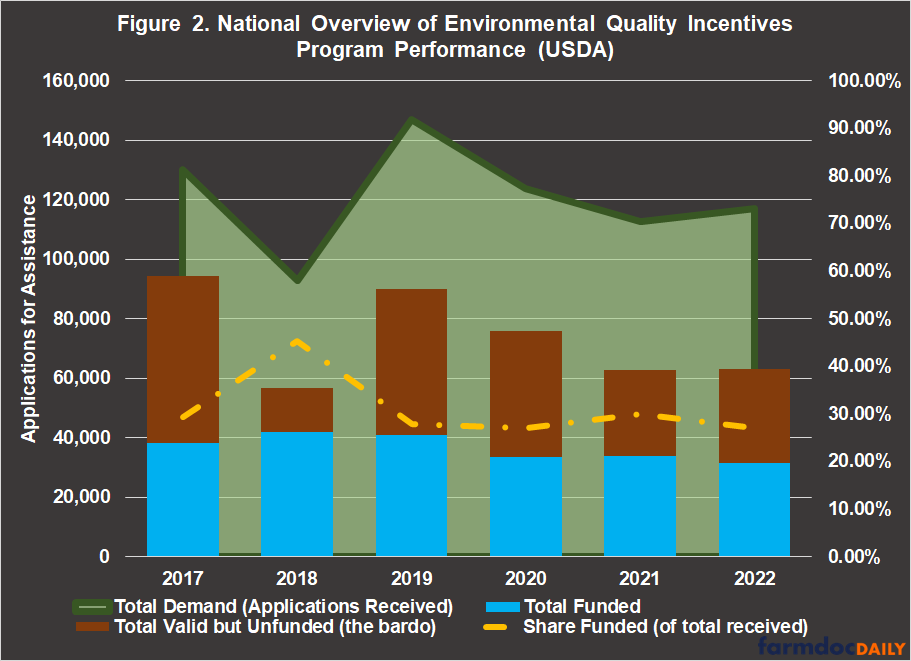

What does the conservation bardo look like for farmers who apply to EQIP? Figure 2 provides a national overview for all states. Figure 2 has been compiled from the data reported to Congress by USDA’s Office of Budget and Program Analysis (OBPA) in the annual explanatory notes for the Congressional justifications to the President’s budget (USDA-OBPA, Congressional Justifications: Explanatory Notes). Overall, NRCS received an average of 120,606 applications each year reviewed here (2017 to 2022). Of those applications received, NRCS averaged 36,620 that were funded each year (31%) and 37,110 that were valid but unfunded each year. This also leaves about 46,876 applications per year that were received but neither funded nor considered valid (average 2017-2022). This latter group of applications are presumed invalid or otherwise not acceptable and are not considered further in this discussion.

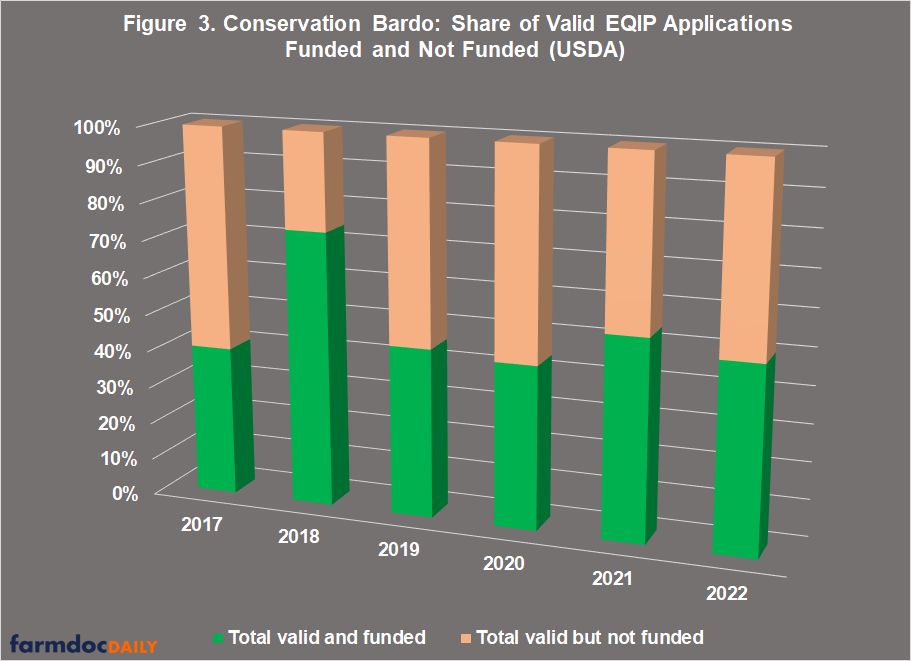

Combining the applications funded and those valid but not funded provides a total set of applications and farmers that applied for EQIP funding to implement conservation on their farms and were approved. On average, NRCS received 73,730 valid applications from 2017 to 2022 and funded an average 36,620 each year from 2017 to 2022 (51%). From this, the 37,110 applications (average 2017 to 2022) that were considered valid but not funded are those in the conservation bardo. On average, 49% of the valid applications end up in this category each year. Figure 3 compares the share of valid EQIP applications that were funded and not funded in each year.

Figure 4 brings the USDA data together in an interactive map of the EQIP conservation bardo. The map displays each State’s average percent of unfunded valid EQIP applications from 2017 to 2022. Hovering over a state presents the annual estimated amount for the unfunded but valid EQIP applications and the total unfunded valid applications for each year.

The data in Figure 4 can also be compared to the total amount in EQIP funding in each state as reported earlier (see, https://policydesignlab.ncsa.illinois.edu/eqip; or farmdoc daily, April 13, 2023). This provides further perspective but is limited in important ways. The data presented in this discussion is limited because USDA has not reported the valid unfunded applications or estimated amounts by conservation practice or category of practices. Such data would provide a more complete picture of the farmers in the EQIP conservation bardo, as well as the conservation practices for which those farmers applied for assistance but did not receive the assistance. It would be particularly informative to know the differences in unfunded valid applications for livestock practices and crop practices in each state.

Concluding Thoughts

The fundamental problem for conservation policy is funding. Congress caps the funds available (i.e., EQIP is limited to $2.025 billion per fiscal year; CSP, $1 billion per fiscal year) or the acres permitted for enrollment (i.e., CRP is capped at 27 million acres). These caps or limits are not based on demand for the program, or the need for assistance, by farmers. In fact, there could be on average twice as many farmers seeking EQIP funding than Congress has made available. These are arbitrary, political decisions by Congress in the Farm Bill. If that point doesn’t register, try a thought experiment: imagine the outcry, the uproar, and even the outrage if half of all farmers enrolled in ARC and PLC were denied payments because Congress limited the funding; better yet, imagine the reaction if half of all farmers who paid for crop insurance were denied indemnities for losses because the funding was limited.

Congress treats conservation differently and the consequences are born out on the ground. For example, research has found that a farmer could spend from 6 hours to 15 hours on the conservation application process (Espinosa Diaz et al., 2023; McCann and Claassen, 2016; McCann and Claassen, 2014). To invest that time on paperwork and not receive the funding, even though it was valid, would be frustrating (at the least). The conservation bardo also costs agency resources, as well as agency employee time; for conservation, moreover, it could also cost the time of technical service providers. Finally, unfunded valid applications for assisting the adoption of conservation practices likely results in those farmers not implementing or adopting the conservation practices on their farms and in their fields. The consequences of the conservation bardo extend to lost opportunities at reducing soil erosion, the degradation of water quality, and other natural resource concerns.

This treatment of conservation investments by Congress possesses a long history and begs many questions; among them, why public funds for policies that have a more direct benefit to the public funding them (i.e., conservation) are limited when public funds for policies that generally only directly benefit the farmers receiving them (i.e., Title I farm payments) are not. A more focused point for the current farm bill negotiations involves the search for offsets to cover the projected costs of increasing farm program payments (see e.g., farmdoc daily, September 14, 2023). While much attention is paid to the demand for higher price triggers, it would seem only reasonable to give more consideration to the farmers in the conservation bardo and to questions about which should be the priority. It is possible that raising reference prices will benefit some farmers at some point in the future, but it is certain that cutting conservation funding to cover the CBO projections will put more farmers in the conservation bardo and reduce investments in practices that could benefit everyone. Doing so would seem not only deficient in justification but also rather far removed from the realm of reason.

References

Alfaro, Mariana, Leigh Ann Caldwell, Marianna Sotomayor, and Jacob Bogage. “Senate moves forward on short-term deal to avert government shutdown.” The Washington Post. September 26, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/09/26/senate-announces-short-term-deal-avert-government-shutdown-future-house-unclear/.

Bogage, Jacob and Marianna Sotomayor. “Shutdown odds grow as House GOP leaders reject Senate’s spending bill.” The Washington Post. September 27, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/09/27/government-shutdown-house-rejects-senate-spending-bill/.

Carney, Jordain and Olivia Beavers. “McCarthy still lacks votes for GOP stopgap, increasing odds of a shutdown.” Politico.com. September 27, 2023. https://www.politico.com/live-updates/2023/09/27/congress/mccarthys-spending-strategy-falls-flat-00118384.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023: Trying to Reason with 1,000 CBO Scores." farmdoc daily (13):167, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 14, 2023.

Coppess, J. and A. Knepp. "A View of the Farm Bill Through Policy Design, Part 1: EQIP." farmdoc daily (13):69, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 13, 2023.

Espinosa Diaz, Salomon, Francesco Riccioli, Francesco Di Iacovo, and Roberta Moruzzo. “Transaction Costs in Agri-Environment-Climate Measures: A Review of the Literature.” Sustainability 15, no. 9 (2023): 7454.

Everett, Burgess. “The Senate’s stopgap funding bill is less than 24 hours old. Some Republican senators already want changes.” Politico.com. September 27, 2023. https://www.politico.com/live-updates/2023/09/27/congress/gop-senators-spending-shutdown-cr-00118392.

Everett, Burgess, Sarah Ferris, Caitlin Emma, and Ursula Perano. “Senate moves shutdown-prevention plan that’s ‘not gonna happen’ in House.” Politico.com. September 26, 2023. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/09/26/senate-shutdown-prevention-plan-00118277.

Hiltrop, Marleen, and Sara Polak. “George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo: semiotic explorations of Abraham Lincoln in American cultural memory.” Rethinking History 26, no. 4 (2022): 551-568. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13642529.2022.2135818

Levitsky, Steven and Daniel Ziblatt. Tyranny of the Minority: Why American Democracy Reached the Breaking Point (New York: Crown Publishing Group, 2023).

McCann, Laura, and Roger Claassen. "Farmer transaction costs of participating in federal conservation programs: Magnitudes and determinants." Land Economics 92, no. 2 (2016): 256-272.

McCann, Laura MJ, and Roger Claassen. Are Farmer Transaction Costs a Barrier to Conservation Program Participation? No. 329-2016-12984. 2014. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/170390/files/TC%20McCann%20Claassen%20AAEA%20sent.pdf.

Saunders, George. “What Writers Really Do When They Write.” The Guardian, March 4, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/04/what-writers-really-do-when-they-write.

Whitehead, Colson. “Colson Whitehead on George Saunders’ Novel About Lincoln and Lost Souls.” The New York Times, February 9, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/09/books/review/lincoln-in-the-bardo-george-saunders.html.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.