Swampbuster Stands, Part 1: Reviewing the Iowa Lawsuit Challenging Conservation Compliance

For forty years, conservation compliance has operated to discourage farmers from converting wetlands or native sod to cropland, as well as from farming on highly erodible fields without a conservation plan to address erosion. On April 16, 2024, CTM Holdings, LLC, (CTM) filed a lawsuit against USDA over the application of conservation compliance, specifically, wetlands compliance (known as Swampbuster) to its farm. On May 29, 2025, the United States District Court for the Northern District of Iowa ruled against CTM and in favor of USDA and conservation compliance. This article initiates a series discussing the case and the court’s ruling, as well as the potential implications for agricultural and conservation policy. In summary, the court found that CTM did not have a cause of action for its claims or standing to bring the lawsuit. The court also went further and reiterated that Swampbuster is a valid exercise of Congress’s spending power.

Background on Swampbuster

In the landmark Food Security Act of 1985, Congress created conservation compliance to address the substantial soil erosion and other conservation challenges that arose during the acreage expansion and farm consolidation of the 1970s. The policy response built over multiple years and Congresses. One of the catalysts for conservation compliance was a report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) titled “Protect Tomorrow’s Food Supply, Soil Conservation Needs Priority Attention” (GAO CED-77-30). Congress first responded with the enactment of the 1977 Soil and Water Resources Conservation Act (RCA) (P.L. 95-192), which required USDA to study erosion and conservation problems and report back to Congress with possible policy responses. In 1979, Representative Jim Jeffords (R-VT) introduced the first compliance legislation that would have prevented farmers from receiving farm support payments unless they had implemented conservation plans (96 H.R. 3681). In 1981, Senator William Armstrong (R-CO) made it bipartisan and bicameral introducing legislation to prohibit price supports if the crops were produced on ground that had not been farmed in the ten preceding years; applicable only to lands west of the 100th meridian, he argued that it was not a wise use of federal funds to encourage production on such land (97 S.1825).

Congress resisted efforts to add conservation compliance to the 1981 Farm Bill or attach it to appropriations bills in 1982 and 1983. The Senate Agriculture Committee reported Senator Armstrong’s conservation compliance bill in 1983 and the House passed a version in 1984, but the bill died in conference (98 S.663). In the 1985 Farm Bill effort, Congress finally enacted conservation compliance. Congress strengthened conservation during debate, including the addition of Swampbuster. Notably, Congress conditioned farm payments on conservation compliance at a time when farmers were struggling during the depths of the Eighties farm crisis; that the provisions faced little opposition, indicated the political strength of the issue when it was enacted (Coppess, 2024).

Since enactment, compliance has been understood by courts as intended by Congress to discourage production on fields where it raises substantial natural resource concerns, including “to combat the disappearance of wetlands though their conversion into crop lands” (B & D Land & Livestock Co. v. Schafer; 16 U.S.C. § 3821). Swampbuster operates by conditioning farm benefits on conserving wetlands or establishing new wetlands in place of ones converted to crop land. Since its inception 40 years ago, multiple agribusinesses and organizations have challenged the constitutionality of the Swampbuster provision to no avail (See e.g., U.S. v. Dierckman; Horn Farms, Inc. v. Johanns).

Background on the Facts of the Lawsuit

The following background information discussed herein has been summarized from the complaint and other documents produced during discovery in the case. The plaintiff in the case is CTM Holdings, LLC, an Iowa limited liability company. CTM and an affiliated entity (B&C, LLC) own over 1,000 acres of farmland. The two LLC’s lease all land to tenants who farm it on a cash lease basis.

On September 30, 2022, CTM purchased three contiguous parcels that comprise 71.85 acres of farmland in Delaware County, Iowa. Of that total, 39.83 acres were tillable and used for farming. Another 21.62 acres are forest, of which nine were previously determined to be a wetland by USDA. The property also includes 10.4 acres that were enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) under a contract that began May 1, 2010, and expired on September 30, 2024. CTM purchased the land while it was still under the CRP contract.

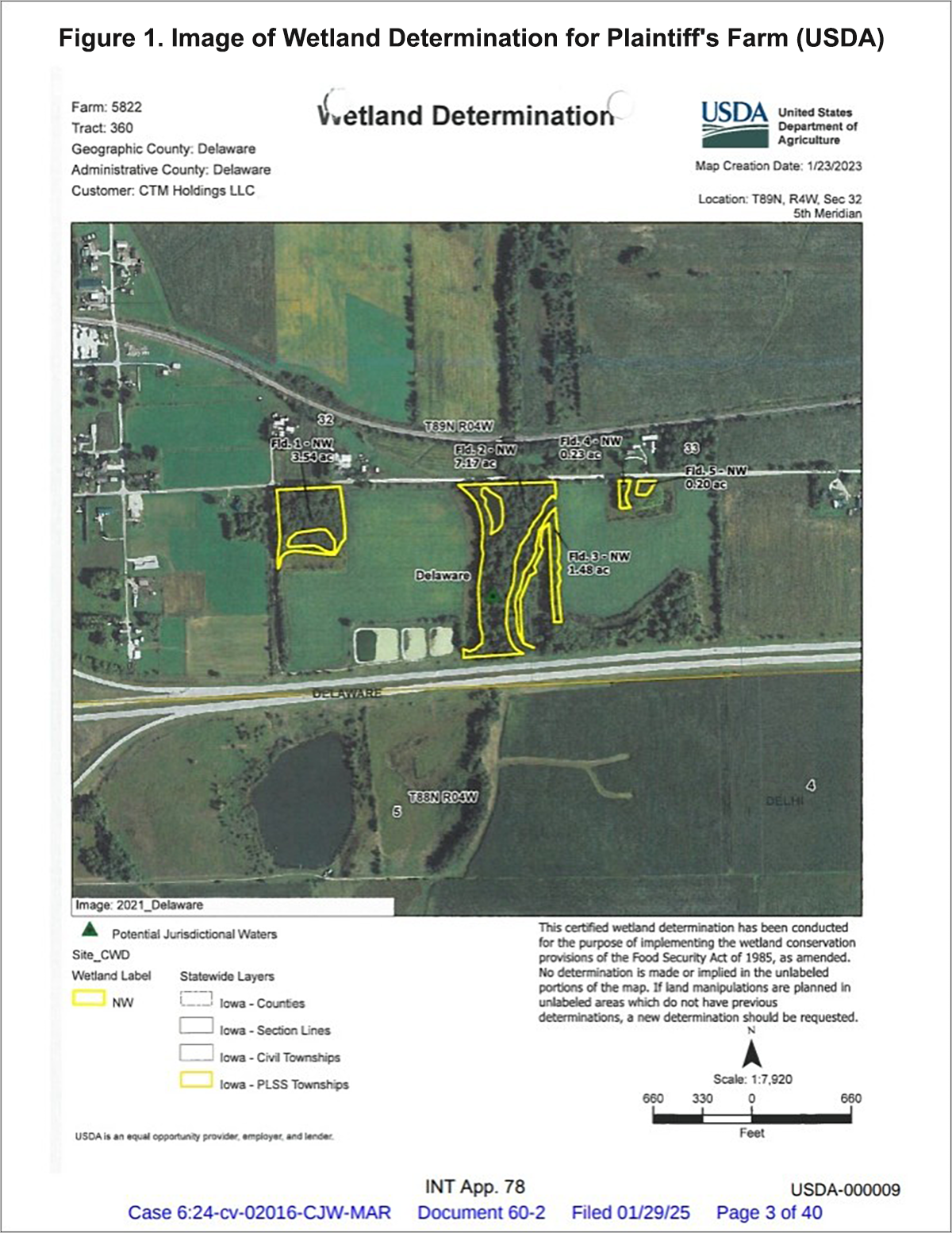

The lawsuit involves the nine acres within the 21.62 acres of forest that were determined to be wetlands by USDA. Figure 1 is the map of the farm included in the wetlands determination dated January 23, 2023. That determination was the result of a request by CTM. The initial wetlands determination was dated April 16, 2010, with another map and determination dated March 18, 2009. Communications between plaintiff and USDA prior to purchase of the land indicate that the plaintiff was aware of the wetlands determination prior to purchase of the property.

The wetlands determination had been made for more than a dozen years prior to CTM’s purchase of the property. Thus, CTM purchased the property with knowledge of that fact. After purchase, CTM notified USDA of its plans to remove the trees and stumps from the forested area to prepare it for farming. CTM also indicated a plan to remove the trees but not the stumps from the wetlands acres, to avoid violating the wetlands restrictions. In response, USDA informed CTM of the need for a wetland determination on the approximately 12 acres that had not previously been determined a wetland. CTM filled out the USDA form (AD-1026) and USDA surveyed the twelve acres, determining that they were not a wetland.

The problem for CTM was that the more recent determination did not change the previous wetlands determination on the nine acres, which CTM wanted to move forward with the conversion to crop land. USDA informed CTM that the time to appeal the 2010 wetland determination had expired but there where still options moving forward: the denial of the appeal itself could be appealed, and additionally, CTM could seek a review of the initial determination. The letter from USDA provided information on who to contact and how to begin that review process. Rather than continue to work within the USDA process, however, CTM filed a lawsuit.

Ultimately, the court found that CTM lacked standing to sue USDA under Section 702 of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) (5 U.S.C. §702) and under the case or controversy requirement in the U.S. Constitution (U.S. Const., Art.III §2, cl.1). To have standing to sue under Section 702 APA, the agency action at issue must be a “final agency action.” Here, it was not. Additionally, to meet the case or controversy requirement in Article III of the Constitution, a plaintiff must show that they suffered an injury in fact, that the defendant’s conduct caused that injury, and that a favorable court decision would redress the injury. Moreover, the plaintiff’s injury “must be concrete and particularized, and actual or imminent, not conjectural or hypothetical” (Lujan v. Defs. Of Wildlife). Here, the court concluded that CTM did not meet this constitutional requirement.

The facts of the case make it clear that USDA’s letter to CTM explaining how to get a review of the wetlands determination did not constitute a final agency action. In short, CTM took a wrong turn after receiving that letter when it stopped working with USDA and turned to the courts. The court explained that turning to the courts before a final agency action left open a “speculative chain of possibilities” (CTM Holdings (quoting Clapper v. Amnesty Int’l USA)). In one possibility, CTM could have requested a review of the 2010 wetlands determination for the nine acres. In another, CTM could have converted the acres determined to be wetlands and left it up to USDA to determine whether the actions had more than “a minimal effect on the wetland functions” (7 C.F.R. §12.5(b)(1)(v)). In this possibility, if USDA did determine the converted acres had more than a minimal effect, regulations would require USDA to give CTM an opportunity to mitigate the loss of wetlands (7 C.F.R. §12.5(b)(4)).

The existence of each of these possibilities, importantly, means that CTM might not have suffered any sort of actual injury—i.e. it might not have lost any benefits. Because CTM ultimately might not have suffered an injury, courts are incapable of rendering judgment on the merits of the case due to a lack of standing. Without a final agency action, any decision would “require guesswork as to how independent decisionmakers will exercise their judgement” (quoting Clapper, 586 U.S. at 413). In other words, because CTM’s injury was speculative, rather than actual or imminent, the court found that it lacked standing to sue (CTM Holdings, LLC v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric.).

Conclusion

Conservation compliance, including the Swampbuster provisions at issue in the lawsuit discussed in this article, were the policy response to substantial problems on the ground and for farm fields. Those problems can be traced to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s and a return of wind erosion problems during droughts of the 1950s. More directly, conservation compliance traces to the reckless policy decisions in the early 1970s, including the Agriculture and Consumer Protection Act of 1973 (P.L.93-86). In that Farm Bill, Congress explicitly encouraged farmers to expand their farms and put more acres into production—the legislative directive backing up the infamous exhortations of former Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz to “plant fence row to fence row” and “get big or get out” of farming (Rosenberg and Stucki, 2017; Chen, 1995). In response, American farmers brought nearly 57 million acres into production by 1981 leading to another soil erosion crisis and eventually the eighties farm economic crisis. The visceral consequences of illogical farm policy seeded conservation compliance and should remain as important context to any challenges to it.

This article discussed a recent challenge to conservation compliance out of Iowa. In summary, the plaintiff lost on a motion for summary judgment because the court found that the plaintiff did not have standing to sue USDA. That decision was based on the failure of the plaintiff to have suffered any actual injuries because USDA had not taken any final agency action against the plaintiff. The plaintiff’s complaint did not end there, however, and raised interesting and important constitutional questions about Swampbuster. These questions appear to be based on the penalties of violating conservation compliance, namely that the violator would be deemed ineligible for all federal farm assistance. Future articles in this series will review these constitutional issues.

References

B & D Land & Livestock Co. v. Schafer, 584 F. Supp 2d 1182, 1190 (N.D. Iowa 2008)

Chen, Jim. “Get Green or Get Out: Decoupling Environmental from Economic Objectives in Agricultural Regulation.” Okla. L. Rev. 48 (1995): 333.

Clapper v. Amnesty Int'l USA, 568 U.S. 398, 412 (2013).

Coppess, Jonathan. Between Soil and Society: Legislative History and Political Development of Farm Bill Conservation Policy (University of Nebraska Press, 2024). https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/nebraska/9781496225146/between-soil-and-society/.

CTM Holdings, LLC v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric., No. 24-CV-2016-CJW-MAR, 2025 WL 1532146 (N.D. Iowa May 29, 2025).

Horn Farms, Inc. v. Johanns, 397 F.3d 472, 477 (7th Cir. 2005).

Lujan v. Defs. Of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 560 (1992).

Rosenberg, Nathan A., and Bryce Wilson Stucki. “The Butz Stops Gere: Why the Food Movement Needs to Rethink Agricultural History.” J. Food L. & Pol'y 13 (2017): 12.

U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office. “Protect Tomorrow’s Food Supply, Soil Conservation Needs Priority Attention.” Report CED-77-30. February 14, 1977. https://www.gao.gov/products/ced-77-30.

U.S. v. Dierckman, 201 F.3d 915, 923 (7th Cir. 2000).

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.