Can China Reduce Soybean Import Demand? Evaluating Soybean Meal Reduction Efforts

Note: This article was written by University of Illinois Agricultural and Consumer Economics Ph.D. student Jilang Qing and edited by Joe Janzen. It is one of several excellent articles written by graduate students in Prof. Janzen’s ACE 527 class in advanced agricultural price analysis this fall.

China relies heavily on soybean imports to meet domestic livestock feed demand. China imports around 100 million tons of soybeans each year, more than 90% of which come from the US and Brazil. For the US, China typically accounts for more than half of US soybean exports, equivalent to roughly one-quarter of total US production in recent years. For Brazil, the dependency is even more pronounced: about 70–80% of Brazil’s soybean exports are destined for China. Changes in China’s demand therefore have substantial impacts on global soybean prices.

Because global soybean production and use are concentrated in a relatively limited number of countries, China, Brazil, and the US are all relatively exposed to soybean market risks stemming from geopolitical tensions, logistical disruptions, and shifts in trade policy. Governments and industry in each country are actively trying to manage this trade-related risk. Policy discussions in this area often focus on making soybean supply chains more ‘resilient’, often through greater self-sufficiency. Brazil and the US, as exporters, try to boost domestic demand, for example using subsidies and mandates for biofuels.

For importers like China, efforts to increase soybean self-sufficiency include strategies to reduce soybean meal use (Cao and Thukral, 2025) and expand domestic soybean production. We focus this article on soybean meal use. China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) estimated the soymeal inclusion rate, the share of soybean meal in domestic feed, to be around 17% in 2017. Following the implementation of a soybean meal reduction policy described below, the official government-estimated inclusion rate fell to below 13% in 2023. This article reconciles this apparent success in reducing soybean meal demand with other data sources on soybean imports and use.

China’s soybean self-sufficiency trajectory has significant implications for the structure of international soybean trade and the dynamics of global oilseed markets. We find China has made limited progress toward self-sufficiency: soymeal inclusion rates have declined but not as sharply or smoothly as official figures suggest and China’s overall soybean import demand remains high. Consequently, impacts of China’s soybean meal reduction policy on major soybean exporters like the US and Brazil is likely to be small in the near term, though the possibility of longer-run demand adjustments cannot be ruled out.

The Path to China’s Soybean Import Dependence

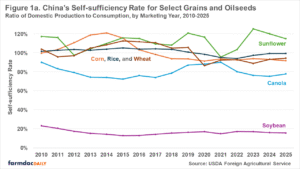

The self-sufficiency rate, or the ratio of domestic production to domestic consumption, describes the degree to which imports and existing inventories are necessary to fulfill commodity demand. Persistent imbalances reflect import dependence. In figure 1a, we describe China’s self-sufficiency since 2010 for select grains and oilseeds according to USDA Foreign Agricultural Service data. It shows China is close to self-sufficient in staple grains such as corn, rice, and wheat. Self-sufficiency in oilseeds is lower and more variable. China is basically self-sufficient in sunflower seed and has a canola self-sufficiency rate around 80%. For both staple grains and some oilseed crops, imports may be required in some years, and those imports may be significant relative to global trade, but China’s production and consumption are of similar magnitude.

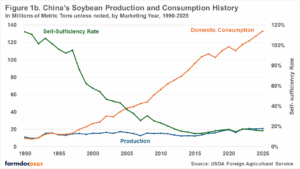

The major exception to China’s relative self-sufficiency in agricultural commodities is soybeans, whose self-sufficiency rate has been just around 20 percent. This level has persisted for a decade or more. China’s import dependence for soybeans originated in the period of rapid economic growth and demographic expansion that began in the early 1990s. At that time, domestic production largely covered domestic use, and the self-sufficiency rate exceeded 100% as shown in Figure 1b. As the Chinese economy boomed, demand for soybeans rose while production did not. Population growth increased overall food requirements, while rising incomes and urbanization triggered a well-documented “nutrition transition” toward greater consumption of animal-source foods (Delgado et al., 1999). This shift sharply raised the need for feed in general, and for soybean meal as the primary protein ingredient in livestock production (Gale, 2015). This created persistent domestic shortfalls, transforming China from a self-sufficient soybean producer into the world’s largest soybean importer.

China’s Soybean Meal Reduction Policy

In 2017, the share of soybean meal in China’s compound livestock feed reached a peak. Subsequent trade frictions with the United States underscored the risk of reliance on imported soybeans and catalyzed a policy push to reduce soybean meal in feed. By 2021, China launched pilot programs to reduce soybean meal use. In 2023, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs issued the “Three-Year Action Plan to Reduce Soybean Meal in Feed”, defining clear targets for the soymeal inclusion rate, the average share of soybean meal in all feed, of less than 13% by 2025 and 10% by 2030.

Chinese policy defines a pathway to lower soybean meal use in feed through lower-protein, amino-acid-balanced diets: feed that has lower crude-protein levels supplemented with essential amino acids such as lysine, methionine and threonine. This strategy maintains livestock growth while enabling feed mills to use less soybean meal. MARA’s technical guidelines call for reducing crude-protein levels in swine and poultry feed by 0.5–1.5 percentage points, with synthetic amino acids filling the nutritional gap. The feasibility of such amino-acid-balanced diets is well established in the animal nutrition literature (Wu, 2014) though researchers continue to assess the merits of replacing soybean meal in feed rations (Cristobal, et al., 2025).

Building on this core strategy, Chinese policy simultaneously promotes several complementary measures to dilute soybean meal’s role in feed rations. These include expanding the use of non-soy protein meals such as rapeseed, cottonseed, peanut, sunflower, and sesame meals; developing new protein resources from distillers’ grains, brewery by-products, crop residues, and sugar-industry by-products; and improving forage structure by producing more high-protein silage and hay. Though not typically thought of as a protein source, increased corn use in feed can partially offset the protein shortfall created by reductions in soybean meal. Although corn contains far less protein than soybean meal on a per-unit basis, its sheer scale of use makes it a significant source of protein in China’s feed industry.

Changes in Chinese Soybean Imports and Soybean Meal Feed Inclusion

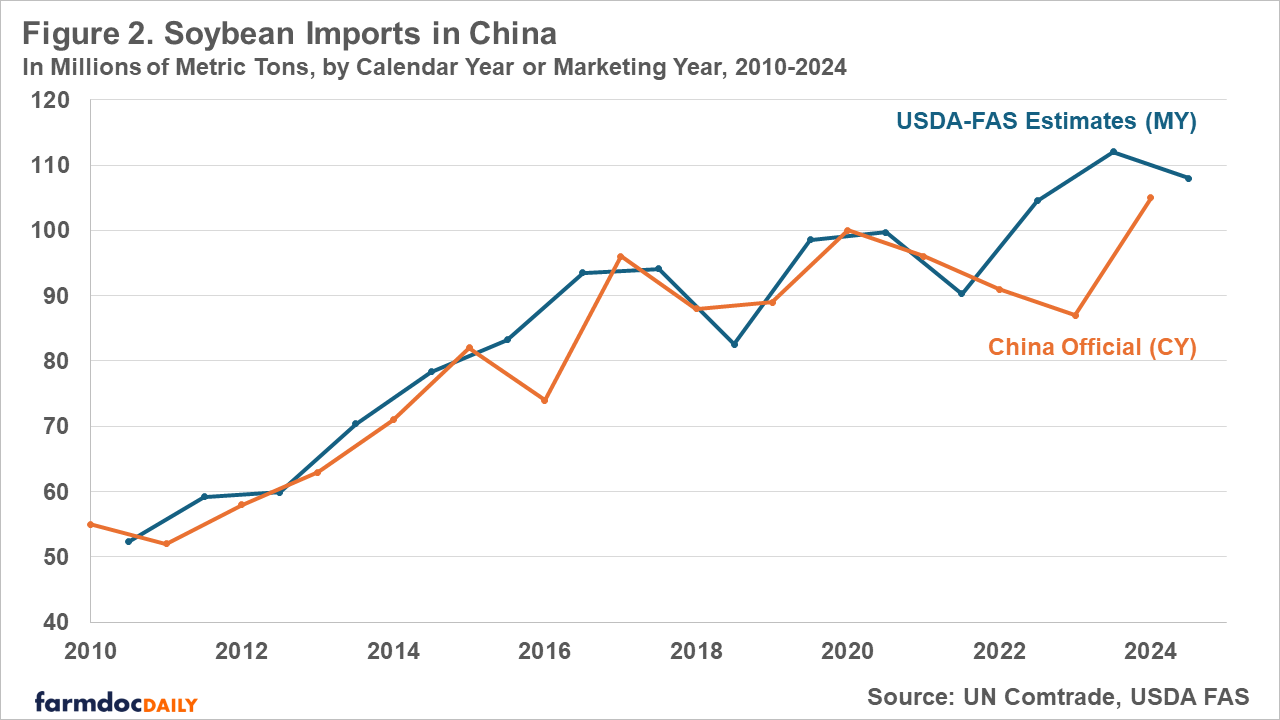

China’s soybean meal self-sufficiency policy targets the feed inclusion rate for soybean meal, but the overall goal is soybean self-sufficiency or reduced import dependence. Official data suggest reductions in soybean meal usage have already occurred. To assess whether the policy is having its intended effect, we first consider the soybean import data during this period. Figure 2 shows the trends in Chinese soybean imports since 2010 according to both official Chinese government statistics and USDA FAS data. Both sources indicate soybean imports have recently hit historic highs, surpassing 100 million tons in the most recent data according to both sources. However, USDA estimates are higher than Chinese statistics in the most recent years. This shows China continues to depend on foreign soybeans, despite recent soybean meal reduction efforts.

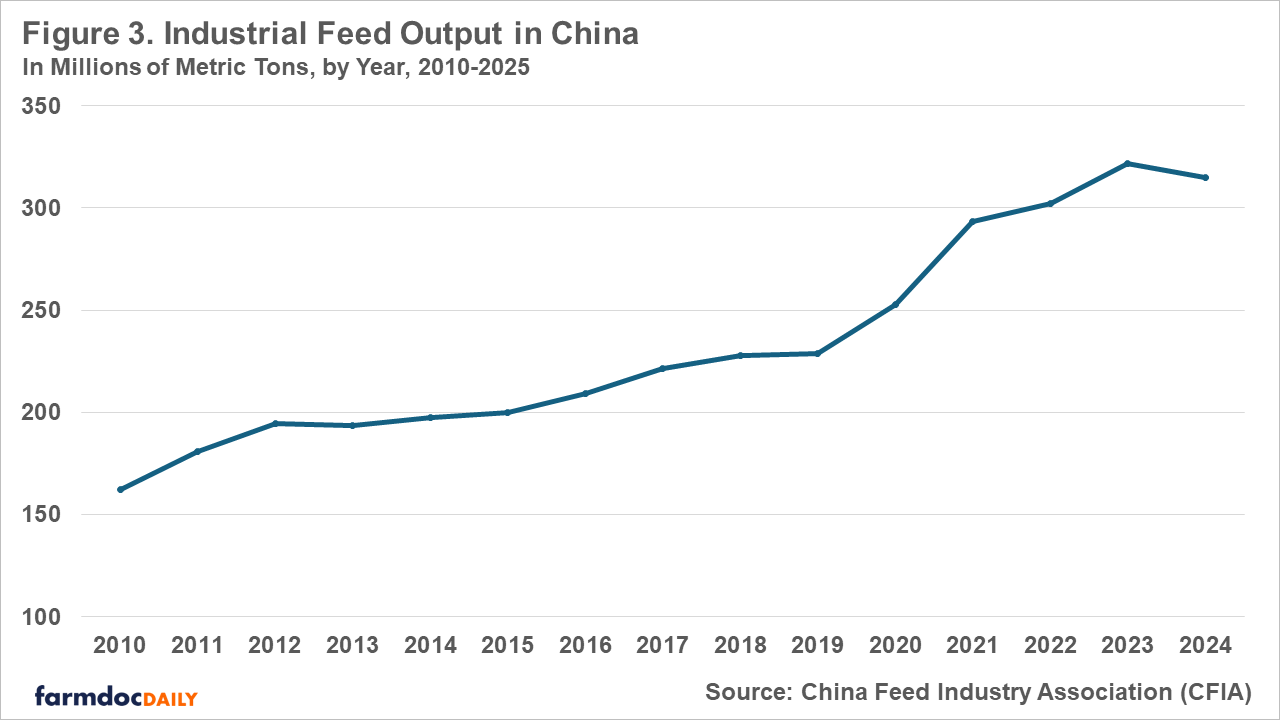

Import data alone cannot fully show that the soymeal inclusion policy has had no effect. Recall that the policy targets the feed inclusion rate, which may be falling even if China continues to be dependent on soybean imports because total feed production has continued to grow, resulting in a higher absolute volume of soybean meal use.

To assess the effect, we look at specific changes in feed output and soybean meal inclusion rates estimated from multiple data sources. Figure 3 reports China’s industrial feed production from 2010 to 2024 according to data from the China Feed Industry Association (CFIA). The figures reported here refer to industrial feed output, which includes compound feed, concentrated feed, and premix feed. There is an overall rise in feed output in this period with the quantity of feed output doubling from 162 million metric tons in 2010 to 322 million metric tons in 2023.

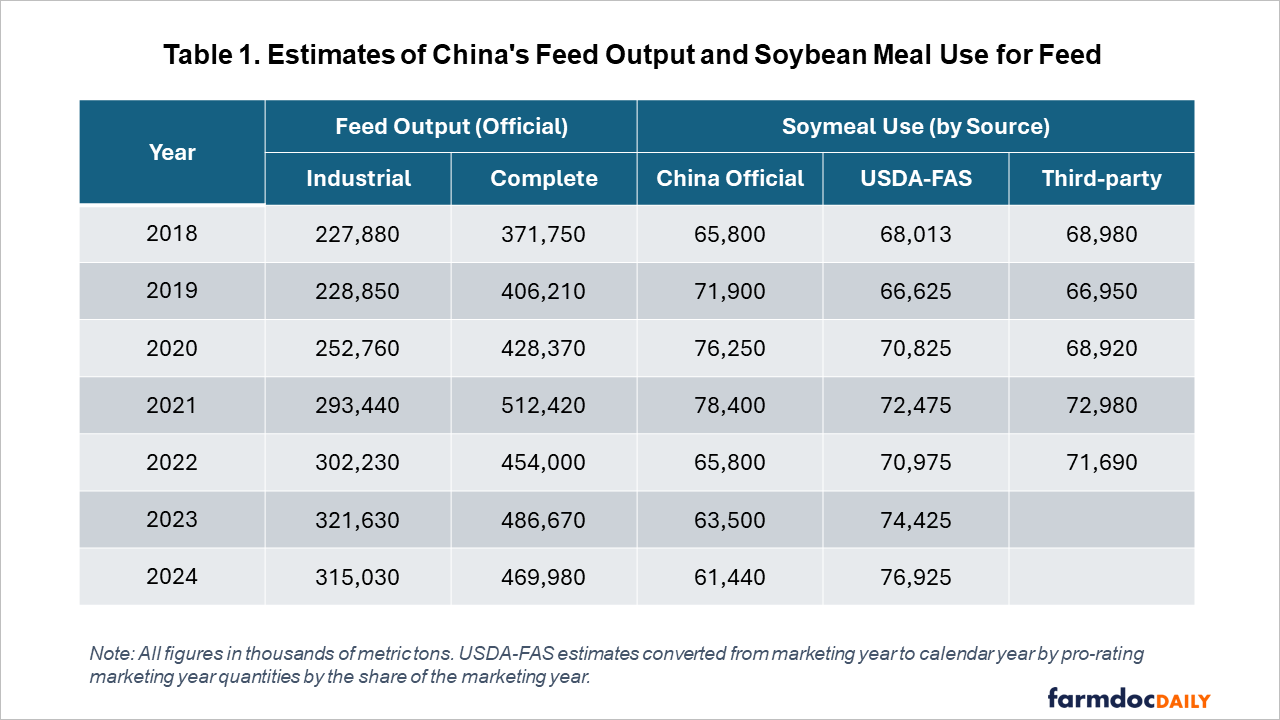

In China’s official calculations of the soymeal inclusion rate, industrial feed output is converted into “full-price” or complete feed, which—aside from moisture, can theoretically meet all an animal’s nutritional requirements and is fed directly to livestock. Compound feed is nutritionally complete and can be fed directly, so it is equivalent to full price feed on a one-to-one basis. Table 1 reports China’s industrial feed output and the corresponding volume of complete feed from CFIA, along with soybean meal use for feed from three different sources: China’s official statistics, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service estimates, and data from Huitong, a third-party industry information provider. These different sources provide a more comprehensive understanding of changes in China’s soybean meal use for feed.

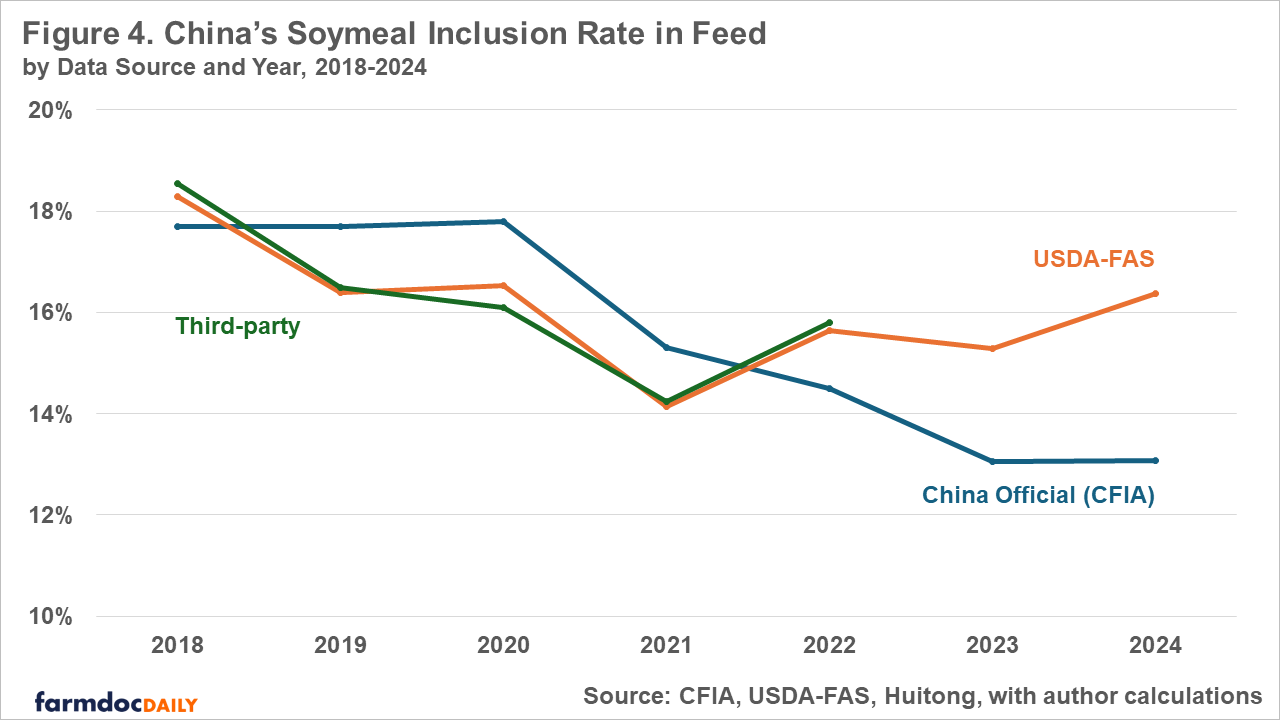

Figure 4 shows the soymeal inclusion rates, the quantity of soybean meal used divided by overall complete feed output computed using different data sources for meal use. Although the overall patterns in inclusion rate changes over time are broadly similar, there are noticeable differences between estimates based on China’s official statistics and USDA estimates. The divergence is most pronounced in 2021-2024: USDA data imply that soybean meal use for feed continued to increase over this period, whereas China’s official series shows a decline in soybean meal consumption. This difference mechanically translates into contrasting trends in the implied inclusion rates: While Chinese estimates show a relatively smooth and continuous decline to around 13%, USDA-based estimates flatten out or even edge up to around 16%. Results using third-party industry data generally corroborate USDA-based estimates, although these data are not available for the most recent years.

Taken together, these results indicate that the official Chinese government data likely overstate the size and smoothness of the reduction in soymeal inclusion rates. A more cautious reading, informed by both USDA and third-party data, is that soymeal inclusion rates in 2024 are modestly lower than in 2018, but the magnitude of the decline is modest and characterized by year-to-year volatility rather than a monotonic downward path.

Limited reductions in soymeal inclusion rates and increased feed production are consistent with data on imports from both China and the USDA which show Chinese soybean imports remain high. The key advantage of USDA commodity supply and demand data is that they are reconciled with global production, consumption and trade data and satisfy the condition that commodity availability must equal usage. USDA data are internally consistent in ways that Chinese government statistics may not be, especially since China does not publish official inventories data.

Discussion

Like many countries, China wants to be self-sufficient for food and agricultural commodities, reducing its exposure to economic shocks from outside its own borders. Reducing soybean meal use is one means for China to become less dependent on imported soybeans. We show existing policies have not yet produced a substantial decrease in soybean meal demand. Chinese soybean imports are large. Soybean meal’s share of China’s feed output has declined modestly and been characterized by fluctuations. These changes are insufficient to offset continued increases in feed output.

Accordingly, the impact from China’s Plan to Reduce Soybean Meal in Feed policy on major soybean exporters is likely to remain limited at this stage. China’s imports of U.S. soybeans fell sharply in recent months, but this decline appears to be driven largely by political rather than economic considerations. On November 7, General Administration of Customs of China (GACC) announced the restoration of soybean export eligibility for three U.S. firms and US export sales of soybeans to China resumed. Both GACC and USDA-FAS projections suggest China will import high levels of soybeans this year (USDA-Foreign Agricultural Service, 2025).

Looking further ahead, however, larger impacts remain possible. China’s soybean meal-reduction measures continue to be enforced and gradually adopted across the feed industry. Supply-side efforts to improve soybean self-sufficiency such as GM soybean cultivation may unlock larger production gains. Most importantly, China’s third consecutive year of population decline and slowing meat consumption growth point to the possibility for a downward shift in Chinese demand for imported soybeans in the longer run.

References

Cao, Ella, and Naveen Thukral. 2025. “China's big feed shift to curb soybean imports, strain small farmers”, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/chinas-big-feed-shift-curb-soybean-imports-strain-small-farmers-2025-06-18/

Cristobal, Minoy, Su A. Lee, Carl M. Parsons and Hans H. Stein. 2025. “Soybean meal remains a valuable pig feed ingredient,” National Hog Farmer, https://www.nationalhogfarmer.com/livestock-management/soybean-meal-remains-a-valuable-pig-feed-ingredient

Delgado, C., Rosegrant, M., Steinfeld, H., Ehui, S., & Courbois, C. (1999). Livestock to 2020: The next food revolution. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO); International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI).

Gale, Fred. 2015. “Development of China’s Feed Industry and Demand for Imported Commodities,” Outlook Report FDS-15K-01, USDA Economic Research Service, https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details?pubid=36930

USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 2025. “China: Oilseeds and Products Report” GAIN Report CH2025-0226 https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Oilseeds+and+Products+Update_Beijing_China+-+People%27s+Republic+of_CH2025-0226.pdf

Wu, G. 2014. Amino acids: Biochemistry and nutrition. CRC Press.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.