A Brief Review of the Consequential Seventies

On August 10, 1973, President Richard M. Nixon signed the Agriculture and Consumer Protection Act of 1973 into law, representing the definitive end to the era of parity policy. Within five growing seasons, however, farmers were driving tractors on the National Mall in protest. Within ten growing seasons, President Ronald Reagan’s USDA unilaterally recreated a Payment-in-Kind (PIK) program to pay farmers to reduce planted acres as the agricultural economy was mired in the worst economic crisis since being rescued by the New Deal. This article reviews pivotal events, policy and related decisions during the consequential decade of the 1970s. Given the current situation and turmoil in the world commodity markets, the review might provide lessons of value, or at least food for thought.

Background

While the Agriculture and Consumer Protection Act of 1973 (P.L. 93-86; the 1973 Farm Bill) marked an important milestone in farm policy history and development, the few years preceding it were particularly notable. With the Agricultural Act of 1970, Congress formally ended acreage controls and replaced the allotment system with set-aside acres, a new policy advocated by the Nixon Administration. Under acreage allotments, the farmer was limited on the acreage planted to a supported commodity but acres taken out of one crop could be planted to other crops, causing problematic acreage shifts. Under set-aside policy, if the Secretary required them, the farmer had to put the acres into conserving uses rather than other crops in order to be eligible for payments under the target price policy (Coppess, 2018). In 1971, Congress expanded lending authority for the Farm Credit System—loosening limitations for the Federal land banks in particular—by enacting the Farm Credit Act of 1971 and implementing the recommendations of the Federal Farm Credit Board’s Commission on Agricultural Credit (Brake, 1974). Running behind these policy changes, President Nixon devalued the U.S. dollar and ended the ability to convert U.S. dollars to gold from 1971 to 1973, altering significantly the export market situation for American farm products (Orden, 2000; Schuh, 1976).

The 1973 Farm Bill is a milestone because it introduced the target price and deficiency payment policy, representing an important shift from price support policy to income support via direct payments, and tightened payment limits ($20,000); it was also notable because it included food stamps for the first time (Coppess, 2018). The magnitude of this shift after four decades of parity policy was highlighted by the fact that the Congressional subtitles included the phrase “Production Incentives” in the new programs of the supported commodities (P.L. 93-86). Fatefully for farmers of wheat, cotton and feed grains, the policy shift represented in this phrasing combined an effective end to acreage restrictions with payments tied to market prices. Figure 1 provides an overview of planted acres for the major commodities using USDA-NASS Quick Stats; the 10-year average of planted acres for each of the major commodities are compared across three decades, the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. On average, farmers planted nearly 264 million acres to these commodities in the Fifties, reduced planting by an average of over 32 million acres in the Sixties and then increased by an average of roughly 27 million acres in the Seventies. More specifically, farmers increased acres planted to the major commodities substantially: 227 million total acres in 1970, compared to 289 million total acres in 1980; an increase of more than 62 million acres planted. Wheat acres experienced the largest swing of more than 32 million acres, from just under 49 million acres in 1970 to almost 81 million acres in 1980.

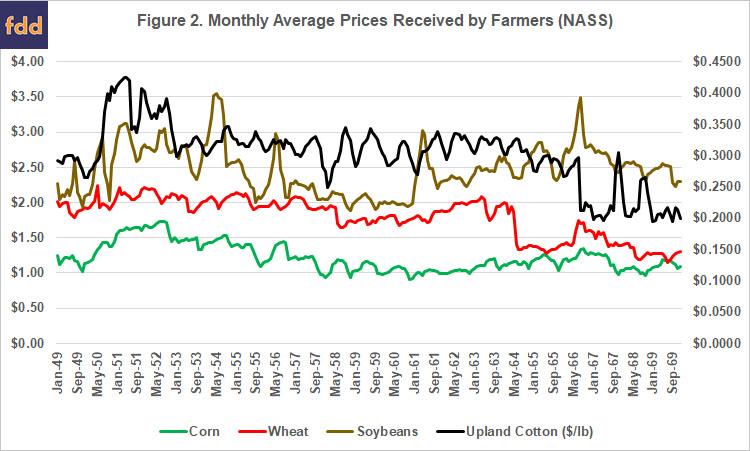

One phenomena of the parity system was the impact on prices; instead of increasing prices, the system appears to have traded off higher prices in return for less volatility. This tradeoff is part of the paradox of the parity system (farmdoc daily, May 16, 2019). To highlight this tradeoff, compare Figure 2 with Figure 3 below. Figure 2 illustrates monthly average prices received by farmers for the major commodities during the post-war parity period, 1949 to 1969.

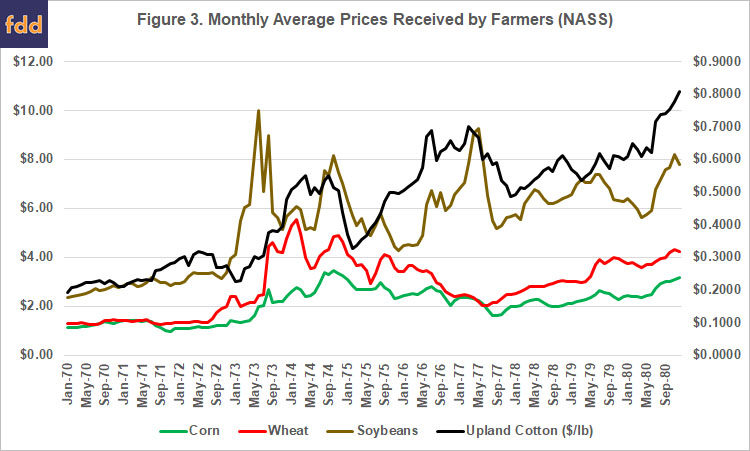

By comparison, Figure 3 illustrates monthly average prices received by farmers from 1970 to 1979. Notable from Figure 3 is the price spike beginning in late 1972 and continuing through 1973 and this will be a focus of the discussion below. The monthly average price received for soybeans reached $10.00 per bushel in June 1973. Wheat prices also spiked, reaching $4.62 per bushel in September 1973 and climbing to a high of $5.52 per bushel in February 1974.

Discussion

The early Seventies price spike is a key piece of the puzzle that was farm policy during the decade and, arguably, the impending economic crisis in the Eighties. While inflation was increasingly an issue in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the price spike in Figure 3 can largely be attributed to a controversial deal with the Soviet Union in 1972 and a decision by President Nixon to temporarily embargo soybean exports in 1973. These, in turn, triggered policy changes and an effort to encourage production; farmers responded to the encouragement but borrowed heavily to achieve it.

(1)The Russian Grain Transactions

Due to drought conditions through winter and spring 1971-1972, farmers in the Soviet Union were estimated to have lost about 25 million acres of winter wheat and were faced with poor conditions for the spring wheat crop. Estimates at the time were that the Soviet Union might end up short more than 700 million bushels of grain production. The Nixon Administration, seeking to improve relations with the Soviet Union, sensed an opportunity and USDA led an effort to orchestrate an unprecedented deal in the summer of 1972. Using Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) authority, USDA agreed to lend up to $750 million to the Soviet Union over three years to help it purchase grain from U.S. grain exporting companies. A Congressional investigation of the deal found that in a series of transactions during July and August of 1972, the Soviet Union purchased approximately 434 million bushels of wheat, 255 million bushels of feed grains and 37 million bushels of soybeans. It was considered the largest sale of grain in U.S. history (S. Rept. No. 93-1033, 1974). Both private and government-owned stocks of grains were effectively emptied; prices soared as planted acreage was slow to respond, further fueling inflation.

Aside from the short-term boost in exports and prices, the deals exposed significant problems. For one, USDA was continuing to operate a special export subsidy program for wheat that was tied to market prices, trigging payments as prices increased. Congressional investigations raised concerns that the grain companies had been able to make unusually large profits, including through manipulating the export subsidy program; over a few months in the wake of the sales to the Soviet Union, the subsidy was estimated to have cost taxpayers $300 million at the time, or approximately $1.8 billion in 2019 dollars (BLS Inflation Calculator). The Russian grain deal also uncovered potential conflicts of interest when a USDA appointee left during the negotiations to take a high-level job with one of the largest grain companies involved in sales to Russia.

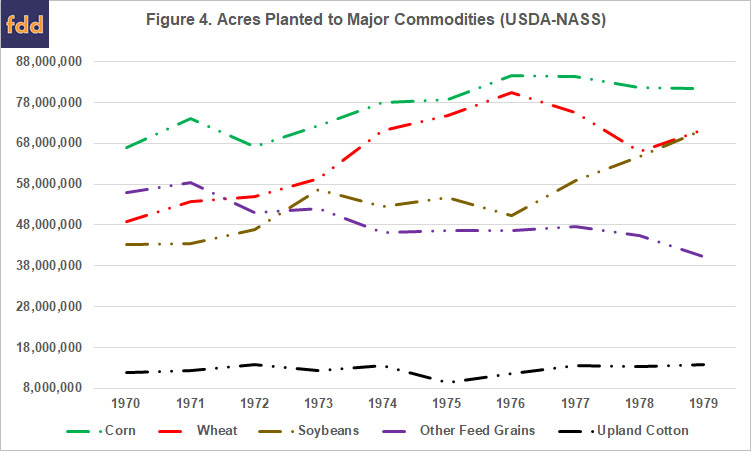

For another, existing farm policy and USDA decisions under the 1970 Farm Bill did not align with the Russian deals. The 1972 Russian purchases represented roughly 28% of the total wheat crop that year. Within a single month, USDA wheat export projections ballooned from 650 million bushels to 1.1 billion bushels; the inability to adjust crop production realities helped add fuel to food price inflation and cost increases (Destler, 1978). An official from the Government Accounting Office told Congressional investigators that he estimated that the total cost to the consumer was $1 billion but USDA Secretary Earl Butz disputed that estimate (S.Rept. 93-1033, 1974). Longer term, the grain transactions, price spikes and inflation concerns fueled the changes in the 1973 Farm Bill and the push to encourage U.S. farmers to plant more acres; 55 million acres were planted to wheat in 1972 and jumped to over 71 million acres in 1974. Figure 4 illustrates the acres planted to corn, wheat, soybeans and the other feed grains (barley, oats, rye and sorghum) as reported by USDA NASS.

(2)The Soybean Embargo

Looking back on 1973 from the vantage point of 1994, former Secretary of Agriculture Edward R. Madigan wrote that it was “hard to believe that the Peruvian anchovy harvest and the Watergate affair could impact on international trade negotiations occurring twenty years later, but those events did have a major effect on trade relations between the United States and the European Community” in the 1980s and into the early 1990s (Madigan 1994). An El Nino event off the coast of Peru harmed the anchovy harvest—an important source of protein for animal feed—contributing to a soybean price spike at a time when the Nixon Administration was trying to control inflation, while battling Congressional investigations (Coppess 2018; Akihiko 2017; Madigan 1994). President Nixon implemented an embargo on soybean (and cottonseed) exports in June 1973. The embargo was short-lived but had far-reaching impacts; the Administration ended the embargo and reinstated contracts by October 1, 1973, when it became clear that the soybean crop was larger than expected.

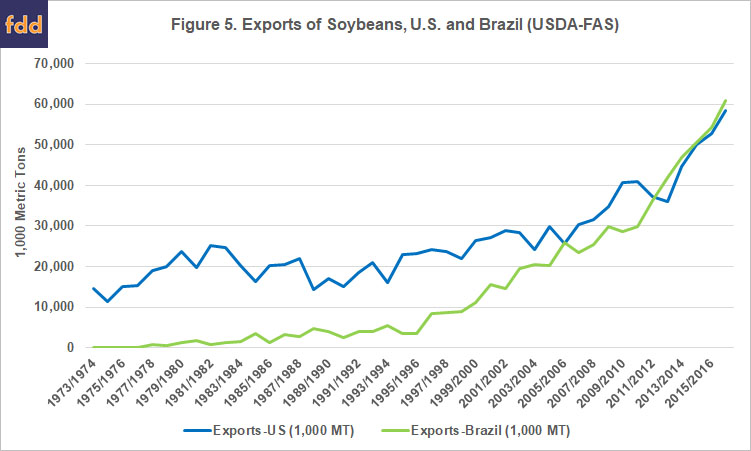

At the time of the temporary embargo, U.S. farmers produced approximately 70% of the total world supply of soybeans. Japan was the largest importer of U.S. farm products, relying on imports for 97% of its soybean needs and U.S. farmers for 90%; the Administration added insult to injury by cancelling soybean contracts and acting without prior consultation with Japan (Akihiko 2017; Marlin-Bennett et al., 1992; Destler, 1976). The embargo raised questions about the U.S. as a reliable supplier of staple commodities. In particular, Japan responded to its over-reliance on the U.S. by introducing the concept of food security and initiating policies to address it. Maybe the most far-reaching of these actions began in 1974 when the Japan International Cooperation Agency was formed and began a large-scale investment in the development of the Cerrado region in Brazil for soybean production; underway from 1979 to 2011 it helped push Brazil into a leading export role in the world soybean market (Akihiko 2017). Also in response, the European Community—another major customer of U.S. soybean exports—began dishing out large subsidies to increase production of oilseed crops in Europe (Madigan 1994). Further illustrating the long-run impacts, Figure 5 charts the exports of soybeans from the U.S. and Brazil in the years following the 1973 embargo based on USDA Foreign Agricultural Service data.

(3)The Farm Credit and Debt Situation

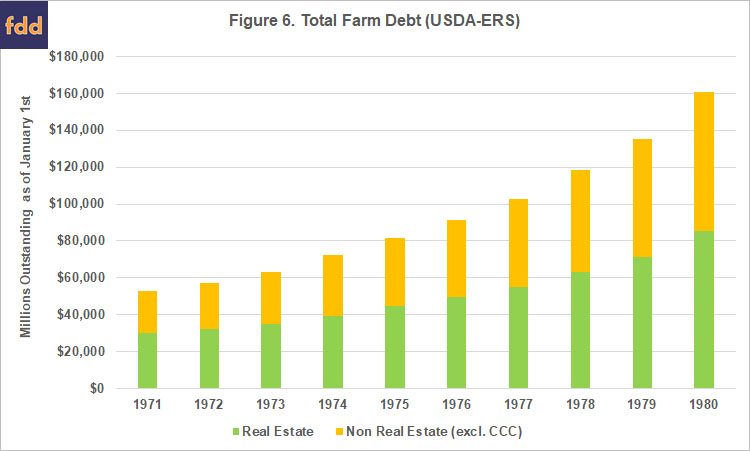

The 1971 Farm Credit Act (P.L. 92-181) added an important piece to the Seventies situation. Among its provisions, Congress made a notable revision to the lending rules for the Federal land banks based upon recommendations from a commission created by the Federal Farm Credit Board. Prior to 1971, Federal land banks were prohibited from making loans that exceeded 65% of the normal value of the agricultural land. With the changes in the 1971 Act, this lending authority was expanded such that Federal land banks were prohibited from making loans that exceeded 85% of the appraised value of the farm real estate value (H. Rept. 92-679, 1971). The full impact of this revision is difficult to untangle from the subsequent events and policy changes discussed above, but it preceded encouragement to farmers to plant more acres and consolidate land holdings. Farmers responded by planting more acres and consolidating, notably taking on much larger debt loads. One estimate was that total farm debt increased from $52.8 billion in 1970 to $178.7 billion in 1980, while the Farm Credit System—including the Federal land banks—drifted into problem territory (Andersen, 2010; Harl, 1990; Sunbury, 1990). Figure 6 illustrates total farm debt from 1971 to 1980 as reported by USDA’s Economic Research Service (Agricultural Finance Outlook and Situation Report, 1984).

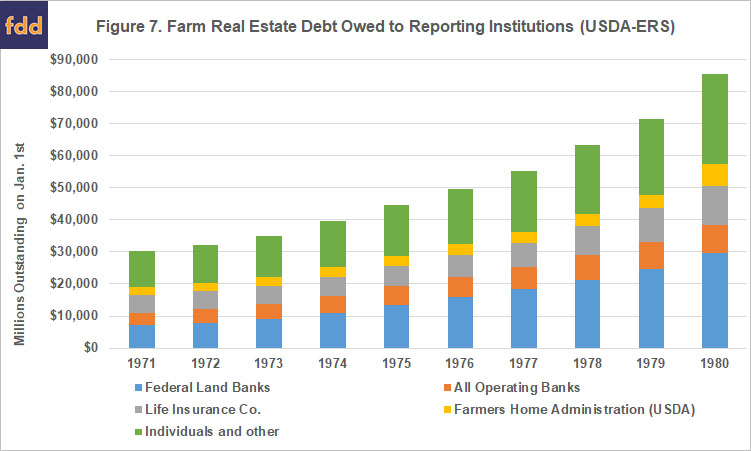

As real estate lending to farmers (green bars) grew during this timeframe, the total real estate loans from institutions also increased its share from 62.5% in 1971 to 67% in 1980, according to USDA ERS. Among institutional lenders, the share for the Federal land banks grew each year from 38% to 52% from 1971 to 1980. Figure 7 illustrates the data provided by ERS for each of the sources of real estate lending to farmers.

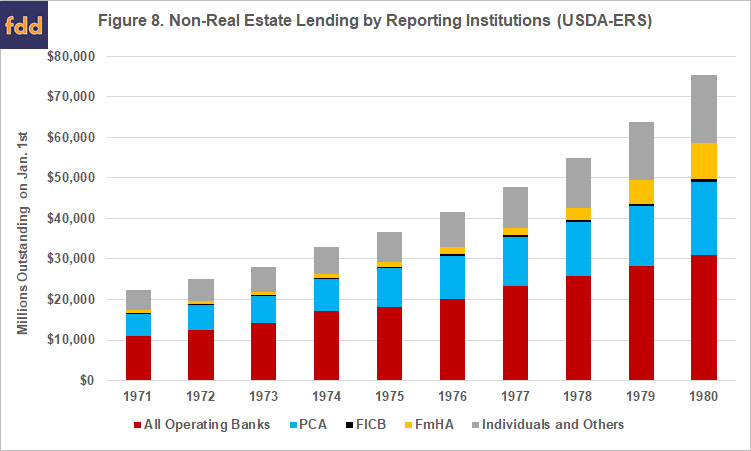

Completing the farm debt picture in the 1970s, Figure 8 illustrates the non-real estate lending by reporting institutions from 1971 to 1980. The reporting institutions include all operating private commercial banks, the Production Credit Associations (PCA) and Federal Intermediate Credit Banks (FICB), as well as USDA’s Farmers Home Administration (FmHA) and loans by individuals or others. Loans from the Commodity Credit Corporation are excluded from the data in Figure 8.

One likely indicator of the increasing financial problems for farmers as the Seventies came to an end could be that the share of non-real estate debt held by banks peaked at 52% in 1974, falling to just over 41% in 1980. At the same time, the lending by FmHA went from a low of under 3% in 1974 to nearly 12% in 1980; lending by individuals and others held relatively steady in the low 20% range, as did the lending share for PCA’s.

Concluding Thoughts

History can be a difficult teacher; whatever clarity may be found in hindsight, the lessons for the present (or future) remain obscure, enigmatic. Part of the challenge is unravelling the vast complexity residing in a confluence of events. The Seventies present a strong example for further study, mixing unpredictable weather events with misguided trade decisions during political turmoil, along with major changes in policy. The decade was bookended with the Russian grain transactions in 1972 and an embargo on grain exports to Russian in 1979. From 1973, when Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz declared that farmers had reached a promised land of strong prices driven by export demand, to 1978 and 1979 when some of those farmers drove tractors on the National Mall in protest, export enthusiasm fueled policy changes which, in turn, fueled expanded production and furthered consolidation. Prices, yields and revenues had all increased but so had costs, debt and financial insecurity; the table was set for the problems that would consume much of the following decade. When the Federal Reserve raised interest rates in 1979 to combat inflation, heavily-indebted farmers were thrown into economic crisis.

References

Akihiko, H. 2017. “Formation of Japan’s food security policy: Relations with food situation and evolution of agricultural policies.” Norinchukin Research Institute Co., Ltd., available online: https://www.nochuri.co.jp/english/pdf/rpt_20180731-1.pdf

Julie Andersen, “Bailouts and Credit Cycles: Fannie, Freddie, and the Farm Credit System,” Wisconsin Law Rev. 1 (2010).

John R. Brake, “A Perspective on Federal Involvement in Agricultural Credit Programs,” 19 S.D. L. Rev. 567, 576 (1974).

Coppess, J. 2018. The Fault Lines of Farm Policy: A Legislative and Political History of the Farm Bill (University of Nebraska Press). Available online: https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/university-of-nebraska-press/9781496205124/.

Coppess, J. "Considering Policy Reversion: The Parity Paradox." farmdoc daily (9):90, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 16, 2019,

Destker, I.M. 1978. “United States Food Policy 1972-1976: Reconciling Domestic and International Objectives.” International Organization, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 617-653.

Dinse, J. and W.P. Browne. 1985. "The Emergence of the American Agriculture Movement, 1977-1979," Great Plains Quarterly. 1832, pp. 221-235.

Madigan, E.R. 1994. “Adverse Consequences of Trade Embargoes,” 27 Creighton L. Rev. 941 (1994).

Orden, D. 2000. “Exchange rate effects on agricultural trade and trade relations.” No. 749-2016-51349, https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/16803/files/ag000006.pdf

Schuh, G.E. 1976. “The New Macroeconomics of Agriculture.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 58, No. 5; pp. 802-811.

Ben Sunbury, The Fall of the Farm Credit Empire (Iowa State U. Press, Ames, IA 1990)

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. 1984. “Agricultural Finance: Outlook and Situation Report,” Economic Research Service, AFO-25, available online: https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/w0892992w/sb397b15x/mc87ps13f/AIS-12-28-1984.pdf

U.S. House of Representatives, “Farm Credit Act of 1971,” Conference Report, H. Rept. No. 92-679 (92nd Congress, 1st Session, November 19, 1971).

U.S. Senate, “Russian Grain Transactions,” Report of the Committee on Government Operations, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, S. Rept. No. 93-1033 (93rd Congress, 2d Session, July 29, 1974).

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.