Another Curious Case for the Supreme Court; A Test for Textualism

The Supreme Court recently granted certiorari in a case reviewing the Clean Air Act and its application to the regulation of greenhouse gas emissions in the effort to address climate change (West Virginia v. EPA, No. 20-1530; ). The following is a review of the statutory interpretation question before the Court.

Background

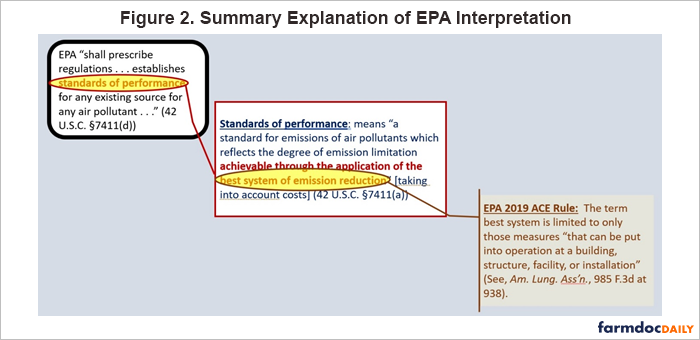

The question posed to the Supreme Court involves the authority of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the Clean Air Act (CAA) to regulate stationary sources of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In particular, the case involves an interpretation of Section 7411(d), which provides a form of catch-all authority—for air pollution not regulated under other provisions—to prescribe regulations that establish “standards of performance for any existing source for any air pollutant” (42 U.S.C. §7411(d)(1)). Congress defined standards of performance as “standard for emissions of air pollutants which reflects the degree of emission limitation achievable through the application of the best system of emission reduction” and takes into account the cost of the system (42 U.S.C. §7411(a)(1)). Figure 1 summarizes the statutory provisions.

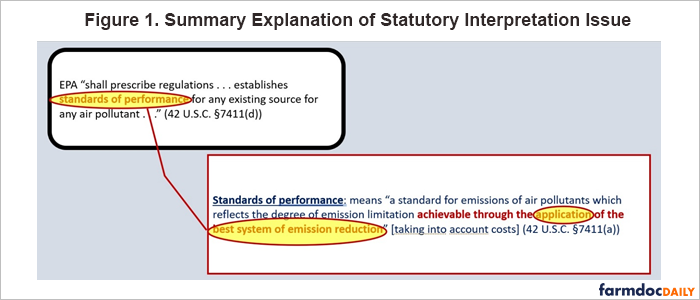

West Virginia, other states and the power-generation industry are seeking Supreme Court review of a decision by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals (Am. Lung Ass’n. v. EPA, 985 F.3d 914 (DC Cir. 2021)). In brief, the appellate court decision reviewed the Trump Administration EPA’s 2019 decision to rescind an earlier regulation (known as the Clean Power Plan) and replace it with the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) Rule. One key issue before the Court is the 2019 EPA interpretation of the statutory definition for standards of performance. EPA limited regulation to only what can be “put into operation at a building, structure, facility, or installation” but not to include any off-site or other measures (Id., at 938). EPA based its interpretation on the meaning of the words “best system of emission reduction” as applicable only to the site of the emissions. Figure 2 adds the EPA interpretation.

Discussion

Textualism is a judicially created method for interpreting statutes that is largely credited to the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. Briefly, textualism works from the premise that only the actual words of legislative text were voted on by Congress and enacted into law. Moreover, all words are to be interpreted or understood in their ordinary, everyday meaning (unless technical) and they should be given the meaning the words had at the time the text was enacted. Textualists tend to oppose the use of other legislative materials, records or history, such as committee reports, for interpretation (Scalia and Garner, 2012; Barrett 2017; Nourse 2019). Textualism offers the appearance of common-sense simplicity. Its actual application to the varieties, vagaries and complexities of statutes can be far more challenging. Far too often, courts become stuck in a battle of dictionary definitions over one or a few individual words within a large, complex statute (see e.g., Bostock v. Clayton County, 140 S. Ct. 1731 (2020); Yates v. U.S., 574 U.S. 528 (2015); Rapanos v. U.S., 547 U.S. 715 (2006); MCI Telecomms. Corp. v. AT&T Co., 512 U.S. 218 (1994)). The case of the ACE rule offers a good example, as well as an interesting test for textualism.

In the decision being reviewed by the Supreme Court, the DC Circuit looked to the ordinary meaning of the words “system” or “best” in the definition and found that EPA’s interpretation was not reasonable, nor supported by the statutory text (Am. Lung Ass’n., 985 F.3d at 946 (citing Sandifer v. U.S. Steel Corp., 571 U.S. 220, 227 (2014)). The court concluded that EPA ignored the actual words of the text, and their meaning, in its “own newfound version” and that it failed to “offer any sound justification for importing language from a different provision” for its interpretation of a “best system” (Id., at 947). Additionally, the appellate court admonished EPA for attempting to rewrite the statute by replacing the “preposition ‘for’ that actually appears in the text” with the “prepositions ‘at’ and ‘to’” for that text in the ACE rule (Id., at 950).

In general, the Supreme Court has found that the CAA includes GHG emissions within the broad, expansive definition of air pollutant and EPA has made the requisite finding that such emissions contribute to climate change and endanger public health or welfare (Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. 497 (2007); Am. Elec. Power Co. v. Connecticut, 564 U.S. 410 (2011); Util. Air Regulatory Group v. EPA, 573 U.S. 302 (2014);Michigan v. EPA, 576 U.S. 743, 751 (2015)). Moreover, the “mere fact that an agency interpretation contradicts a prior agency position is not fatal” (Smiley v. Citibank (S.D.), N.A, 517 U.S. 735, 742 (1996)) because “Agencies are free to change their existing policies as long as they provide a reasoned explanation for the change” (Encino Motorcars, LLC v. Navarro, 579 U.S. 211, 222 (2016) (citing Nat’l Cable & Telecomms. Ass’n v. Brand X Internet Servs., 545 U.S. 967, 981-82 (2005)). Agencies have a degree of flexibility or latitude to adapt rules to changing circumstances (See e.g., Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Ass’n v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 463 U.S. 29, 42 (1983)).

What makes the West Virginia case an interesting test for textualism is that the 2019 EPA interpretation was an effort to significantly curtail EPA’s regulatory authority, rather than the more typical interpretative effort to expand its regulatory authority. The judicial work of textualists has more-often-than-not worked to limit any expansion of agency authority to regulate through narrow, limited interpretations of the delegation of authority by Congress (see e.g., Rapanos v. U.S., 547 U.S. 715 (2006)). The question for the Supreme Court in this case is whether textualism works as an ideological or purposive effort in which it only applies to agency interpretations that the Court deems as seeking to expand authority, or is it an agnostic exercise of interpreting words and phrases regardless of whether the result expands or contracts the authorization? For example, the Supreme Court has instructed that Congress does not “alter the fundamental details of a regulatory scheme in vague terms or ancillary provisions—it does not, one might say, hide elephants in mouseholes” (Whitman v. Am. Trucking Ass’ns, 531 U.S. 457, 468 (2001)). In other words, the test for textualism is whether an unreasonable interpretation remains unreasonable when it narrows or curtails authority to regulate, or does it only apply to expansive interpretations.

Ultimately, the point of statutory interpretation is to uphold the intent of Congress. Statutory words should not be read in isolation or as unrelated terms or phrases (see, Gonzales v. Oregon, 546 U.S. 243, 273 (2006)). Courts are not to read words in a vacuum (see, Gundy v. United States, 139 S. Ct. 2116, 2126 (2019). Courts should look to the “principle evil Congress was concerned with when it enacted” the statute (Bostok, 140 S. Ct. at 1744). For the Clean Air Act, the principle evil was the regulation of any air pollutant. That term now includes GHG emissions and Congress understood “that without regulatory flexibility, changing circumstances and scientific developments would soon render the Clean Air Act obsolete” (Massachusetts, 549 U.S., at 532). EPA cannot use an interpretation that reconfigures the statute in a manner that contradicts what Congress intended (Michigan, 576 U.S., at 757). Nor can EPA use an interpretation “to shirk its environmental responsibilities” (Massachusetts, 549 U.S., at 532).

In the CAA, Congress intended a broad scope of authority for EPA that was flexible and adaptable. That intent would presumably apply when it authorized the use of a standard based on what is achievable through the best system of emission reduction. Arguably that standard should be understood as an intent to push the regulated industry to undertake substantial efforts to reduce pollution in order to promote clean air; to drive adaptation and the adoption of increasingly new, improved or more advanced technologies throughout the sector. If so, it would be an unreasonable interpretation for EPA to restrict the broad, expansive scope enacted by Congress (See, U.S. v. Gonzales, 520 U.S. 1, 5 (1997); Ams. for Clean Energy v. EPA, 864 F.3d 691, 712 (D.C. Cir., 2017)). The principle goal of the Clean Air Act was to reduce air pollution that endangers public health and welfare. That goal does not square well with an interpretation by the agency allowing the agency tasked with the work to unduly limit itself. If the text enacted by Congress was expansive, it should be unreasonable for EPA to narrow or limit it through regulation; an unreasonable interpretation is an unreasonable interpretation regardless of the ideological appeal of it (See e.g., MCI Telecomms. Corp. v. AT&T Co., 512 U.S. 218 (1994)).

Concluding Thoughts

Among the difficult and interesting questions for the Supreme Court in its review of the D.C. Circuit Court decision is whether statutory interpretation is to be agnostic as to the ideological outcome. Whether the interpretation limits an agency’s authority or expands it should not matter if major modifications with substantial economic and political significance constitute an unreasonable interpretation because such decisions were not delegated to an agency in cryptic fashion. Neither the Clean Air Act, in general, nor the provision for specifically achieving reductions in the emissions of air pollution through the best system of emission reduction, fit comfortably within a narrow interpretation of the statutory text. It is ultimately a question of power among Congress, the Executive and the Judiciary. Arguably, an agency should not exercise its power in a manner too limited for what Congress intended any more than it should do so to expand beyond what Congress intended. A deeper, more difficult issue is whether the courts should be in the role of determining these questions because they increasingly risk the promotion of regulation and policymaking by litigation. Behind such esoteric questions of law are vast and profound consequences.

[A note of appreciation to the students taking Agricultural Law (ACE 403) this spring semester for reviewing this case and other questions of statutory interpretation. Their questions and discussions were helpful to working through this difficult case.]References

Barrett, Amy Coney. "Congressional Insiders and Outsiders." The University of Chicago Law Review (2017): 2193-2211.

Nourse, Victoria. "Textualism 3.0: Statutory Interpretation After Justice Scalia." Ala. L. Rev. 70 (2018): 667.

Scalia, A. and B.A. Garner. Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts (St. Paul: Thomson/West, 2012).

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.