International Benchmarks for Soybean Production

Examining the competitiveness of soybean production in different regions of the world is often difficult due to lack of comparable data and agreement regarding what needs to be measured. To be useful, international data needs to be expressed in common production units and converted to a common currency. Also, production and cost measures need to be consistently defined across production regions or farms.

This paper examines the competitiveness of soybean production for important international soybean regions using 2016 to 2020 data from the agri benchmark network. An earlier paper examined international benchmarks for the 2015 to 2019 period (Langemeier, 2021). The agri benchmark network collects data on beef, cash crops, dairy, pigs and poultry, horticulture, and organic products. There are 11 countries with soybean data for 2020 represented in the cash crop network. The agri benchmark concept of typical farms was developed to understand and compare current farm production systems around the world. Participant countries follow a standard procedure to create typical farms that are representative of national farm output shares, and categorized by production system or combination of enterprises and structural features. Costs and revenues are converted to U.S. dollars so that comparisons can be readily made. Data from six typical farms with soybean enterprise data from Argentina, Brazil, Russia, Ukraine, and United States were used in this paper. It is important to note that soybean enterprise data is collected from other countries. These five countries were selected to simplify the illustration and discussion.

The farm and country abbreviations used in this paper are listed in Table 1. While the farms may produce a variety of crops, this paper only considers soybean production. Typical farms used in the agri benchmark network are defined using country initials and hectares on the farm. To fully understand the relative importance of the soybean enterprise on each typical farm, it is useful to note all of the crops produced. The typical farm in Argentina produced corn, soybeans, sunflowers, and winter wheat in 2020. Soybeans were produced on approximately 68 percent of the typical farm’s acreage during the five-year period. The typical farm in Brazil produced corn and soybeans in 2020. Soybeans were the first crop planted on all of the typical farm’s acreage during the five-year period. The farm in Russia produced alfalfa, chickpeas, corn, corn silage, fodder grass, soybeans, summer barley, sugar beets, sunflowers, winter rye, and winter wheat in 2020. Soybeans were produced on approximately 18 percent of the typical farm’s acreage during the five-year period. Crops produced on the farm in the Ukraine in 2020 included corn, soybeans, sunflowers, winter rapeseed, and winter wheat. Soybeans were produced on approximately 13 percent of the typical farm’s acreage during the five-year period. There are four U.S. farms with soybeans in the network. The two farms used to illustrate soybean production in this paper are the Iowa typical farm (US700) and the west central Indiana typical farm (US1215). Both of these farms utilize a corn/soybean rotation.

Soybean Yields

Soybean Yields

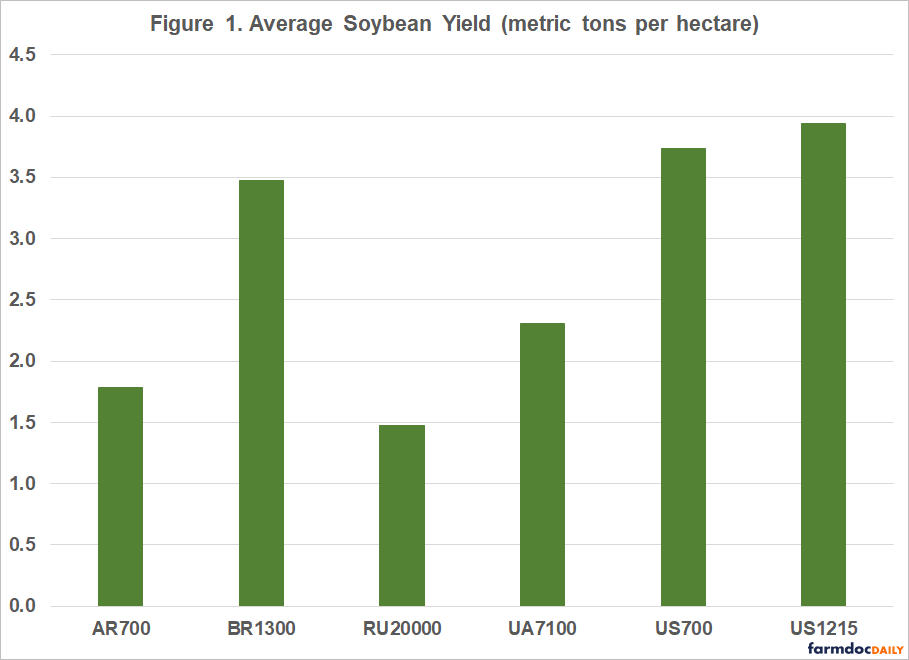

Although yield is only a partial gauge of performance, it reflects the available production technology across farms. Average soybean yield for the farms in 2016 to 2020 was 2.79 metric tons per hectare (41.4 bushels per acre). Average farm yields ranged from approximately 1.48 metric tons per hectare for the typical farm in Russia (21.9 bushels per acre) to 3.94 metric tons per hectare for the typical farm in west central Indiana (58.6 bushels per acre). Figure 1 illustrates average soybean yield for each typical farm. Both of the U.S. farms had average soybean yields above 3.70 metric tons per hectare (55.0 bushels per acre).

Input Cost Shares

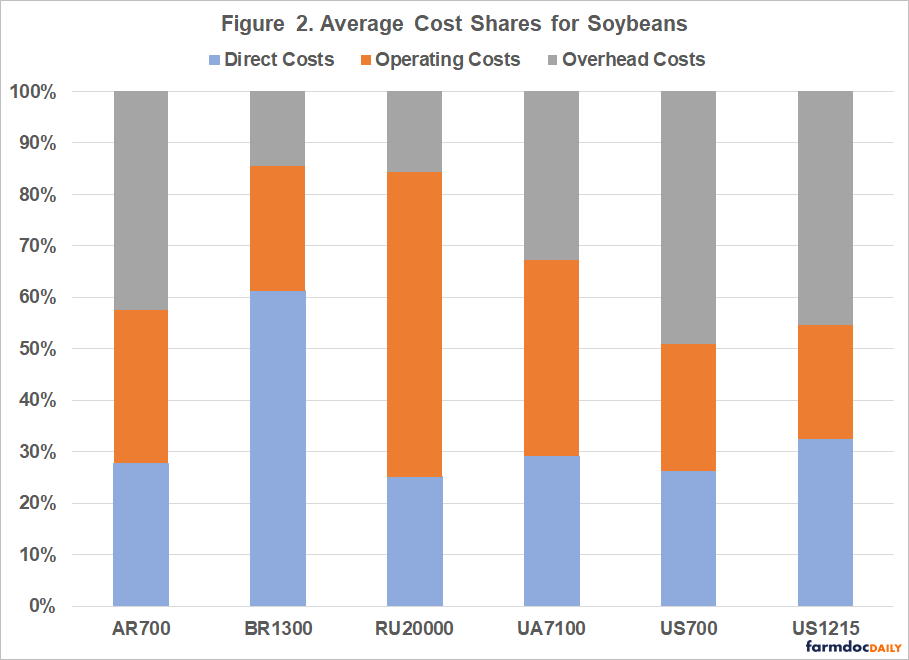

Due to differences in technology adoption, input prices, fertility levels, efficiency of farm operators, trade policy restrictions, exchange rate effects, and labor and capital market constraints, input use varies across soybean farms. Figure 2 presents the average input cost shares for each farm. Cost shares were broken down into three major categories: direct costs, operating costs, and overhead costs. Direct costs included seed, fertilizer, crop protection, crop insurance, and interest on these cost items. Operating cost included labor, machinery depreciation and interest, fuel, and repairs. Overhead cost included land, building depreciation and interest, property taxes, general insurance, and miscellaneous cost.

The average input cost shares were 33.6 percent for direct cost, 33.1 percent for operating cost, and 33.3 percent for overhead cost. The typical farm in Brazil had an above average cost share for direct cost. Operating costs as a proportion of total costs were relatively higher in Russia and the Ukraine. Overhead costs as a proportion of total costs were relatively higher in Argentina and the United States. The relatively large cost share for overhead cost in the U.S. reflects our relatively high land cost.

Revenue and Cost

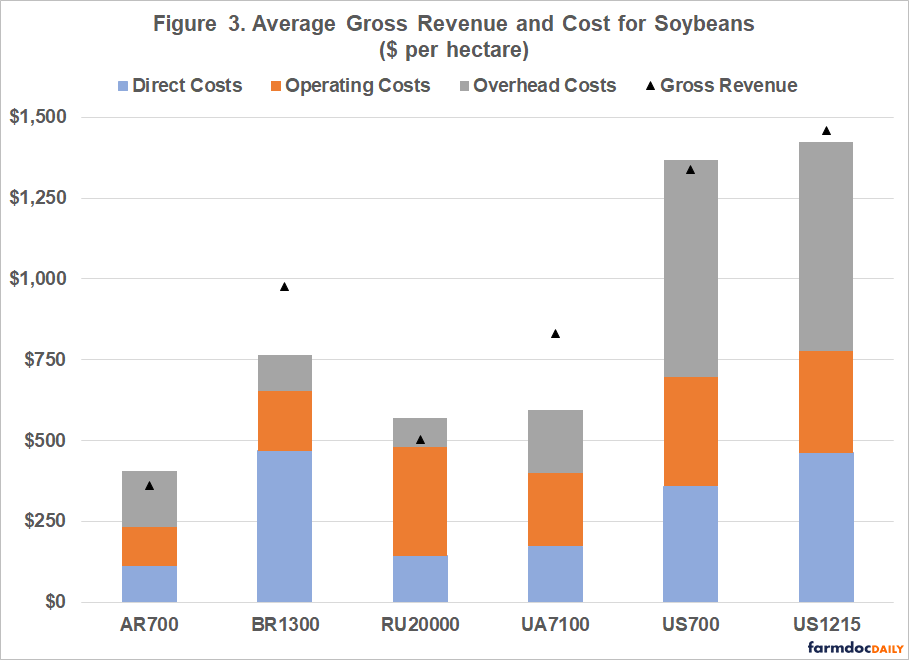

Figure 3 presents average gross revenue and cost for each typical farm. Gross revenue and cost are reported as U.S. dollars per hectare. It is obvious from Figure 3 that gross revenue per hectare is substantially higher for the two U.S. farms. However, cost is also substantially higher for these two farms. The typical farms in Brazil, the Ukraine, and west central Indiana exhibited economic profit during the five-year period. The typical farm in Iowa had a small economic loss during the five-year period. The lowest economic profit during the five-year period for the typical farms was 2019 with an average economic loss of $52 per hectare. The lowest economic profit for each typical farm was as follows: 2016 for the typical farm in Brazil, 2017 for the typical farm in the Ukraine, 2019 for the typical farm in west central Indiana, and 2020 for the typical farms in Argentina, Russia, and Iowa.

All of the typical farms in Table 1 also produced corn during the five-year period. For the typical farms in Brazil, Ukraine, and the United States, average soybean profits were higher than average corn profits during the five-year period. The largest difference in favor of soybeans occurred for the typical farm in Brazil (difference of $258 per hectare). For the U.S. farms, the average difference between soybean and corn profits was $150 per hectare for the west central Indiana farm and $184 per hectare for the Iowa farm. Average corn profits were $254 per hectare higher in Argentina and $59 per hectare higher in Russia.

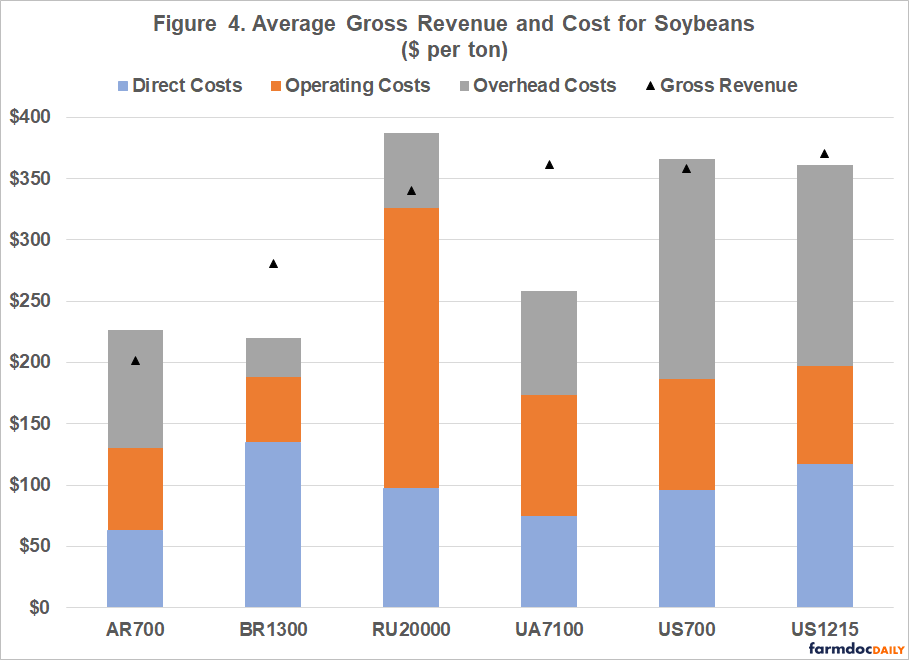

Figure 4 presents average gross revenue and cost for soybeans on a per ton basis. Gross revenue per ton was relatively higher for the two U.S. farms. However, the two U.S. typical farms also had relatively higher costs per ton. Economic profit for the five-year period was positive for the typical farms in Brazil, the Ukraine, and west central Indiana.

Conclusions

This paper examined yield, gross revenue, and cost for farms in the agri benchmark network from Argentina, Brazil, Russia, the Ukraine, and the United States with soybean enterprise data. Yield, gross revenue, and cost were substantially higher for the U.S. farms. The typical farms in Brazil, the Ukraine, and west central Indiana exhibited a positive average economic profit during the 2016 to 2020 period. Soybeans were more profitable than corn during the five-year period for the typical farms in Brazil, the Ukraine, and the United States.

References

agri benchmark. http://www.agribenchmark.org/home.html. Accessed on March 28, 2022.

Langemeier, M. "International Benchmarks for Soybean Production." farmdoc daily (11):102, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 2, 2021.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.