Preparing the Future Food and Agricultural Workforce: Trends in Agricultural-Related Degree and Certification Completions from U.S. Post-secondary Institutions

Addressing the agricultural sector’s workforce needs remains a persistent challenge. Slower migration within the U.S. agricultural workforce, combined with declining immigration, has limited the supply of farm laborers (Hertz and Zahniser, 2013; Charlton, Taylor, Vougioukas, and Routledge, 2019). Many agricultural producers have adopted labor-saving technologies to help mitigate the effects of tight labor markets and rising wages (Stup, Ifft, and Maloney, 2019), but effective adoption and implementation often requires farm operators to develop new knowledge, skills, and abilities within their workforce (Erickson, Fausti, Clay, and Clay, 2018; McFadden, Njuki, and Griffin, 2023).

Farm labor challenges receive much attention, but the agricultural sector must fill a broader array of occupations and many of these occupations require a mix of education, training, and experience (White, Rahe, Milhollin, Horner, Russell, Presberry and Kuhns, 2020). Many of these occupations will not require extensive post-secondary education, but the workforce needs of agricultural producers, suppliers, and service providers will continue shifting as they adopt more automated technologies and engage in more knowledge intensive activities. As a result, their workforce must also evolve to maximize the benefits of these technologies and U.S. post-secondary institutions will play a key role in training and educating this agricultural workforce.

This brief represents the first in a series exploring trends in agricultural-related degree and certification completers from U.S. post-secondary institutions. This first brief relies upon program completer data available through the U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics’ (NCES) Integrated Post-secondary Education Data System (IPEDS).[1] It focuses on the scale of completions over time, and by state, and how award completions vary by program area. These data, therefore, show changes in how many potential new workers are entering this workforce, as well as the agricultural-related fields that attract the greatest student interest.

Animal and Business-Related Programs Produce the Most Agricultural-Related Degrees and Certifications

In 2021, U.S. post-secondary institutions awarded approximately 52,500 degrees and certifications in agricultural-related fields between July 1, 2020 and June 30, 2021.[2] Figure 1 shows the number of awards by program area. [3] Almost half of all awards came from three program areas—veterinary/animal health technologies, animal sciences (incl. animal health and nutrition, dairy science, and livestock management, among other fields), and agricultural business and management. Another third of agricultural-related awards came from programs areas such as veterinary medicine, agricultural production operations, general agriculture, applied horticulture, and plant sciences.

Many different types of institutions awarded these degrees and certifications. For instance, the nation’s 123 land-grant institutions[4] were the leading source of agricultural-related degrees and certifications by accounting for 45.8% of all agricultural-related degrees and certifications during this period. Two-year institutions also played an important role, as 30.0% of these awards went to students completing degrees and certifications at two-year institutions.

Agricultural-Related Post-secondary Awards Grew Since 2003, but Not at the Same Pace as Awards Nationally

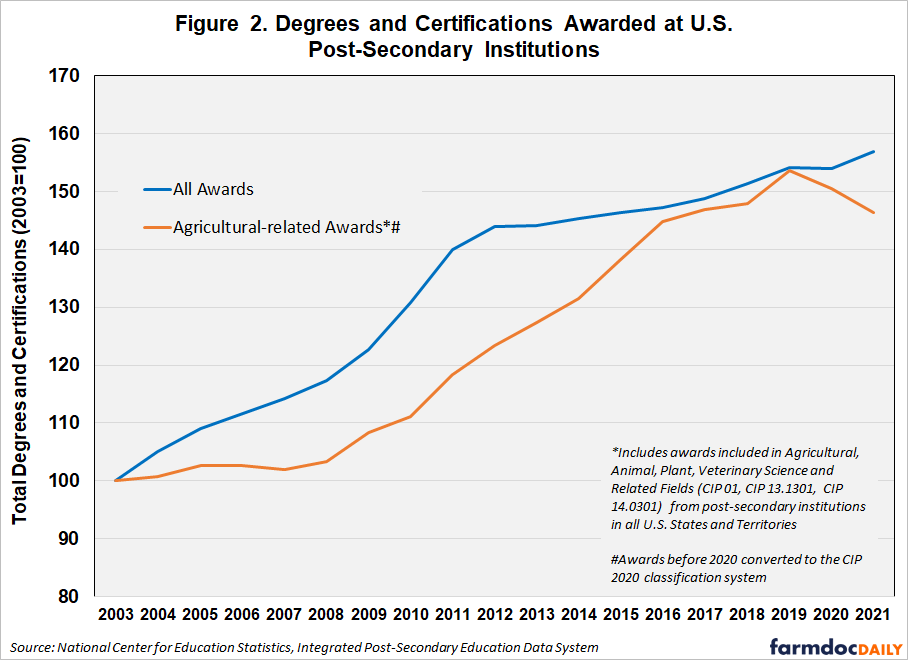

Figure 2 is an index showing the growth in agricultural degrees and awards since 2003.[5] Agricultural-related degrees and certifications have grown 46 percent since 2003, but for most of the past two decades this growth occurred at a slower pace than post-secondary awards overall (which grew 57% during the same period). The relatively larger millennial generation pursuing post-secondary education was an important contributor to this growth, but some program areas also attracted more students than others.

The program area that experienced the largest growth during this period was veterinary/animal health technologies/technicians (+5,573 awards 2003-21). Many graduates from veterinary technician programs find work in practices focused on house pets, but many veterinary practices outside of more dense urban areas are mixed-animal practices that address the needs of both pets and large animals. Other program areas that experienced significant growth during this period included animal sciences (+3,477) and agricultural production operations (+1,871); the latter includes program areas such as crop production, animal livestock husbandry and production, aquaculture, viticulture, etc.

Since 2019, U.S. post-secondary institutions awarded fewer agricultural-related degrees and certifications than in previous years. The programs areas experiencing the greatest declines since 2019 include applied horticulture and horticultural business services (-1,217 awards 2019-2021), agricultural business and management (-812), and veterinary/animal health technologies/technicians (-627). The pandemic likely influenced some these declines; however, they are probably more influenced by the new demographic reality resulting from Generation Z being smaller than the millennial generation. As a result, there are now fewer traditionally aged (i.e., 18-25) post-secondary students (Hetrick, Grieser, Sentz, Coffey, and Burrow, 2021).

Large States Produce the Most Agricultural-Related Awards, but These Awards Represent a Greater Relative Share of the Total in Smaller, Agricultural States

As might be expected, the nation’s largest states accounted for the most degrees and certifications. In 2021, almost 1 out of 4 agricultural-related post-secondary awards came from three states—California (5,930), Texas (4,838) and Florida (2,061). Larger states may produce significant numbers of completers, but Figure 3 shows that agricultural-related awards represent a greater relative share (as measured by location quotients) of total awards in states like Wyoming, South Dakota, Iowa, Nebraska, and North Dakota.[6] Relative to other states, these states have less diverse economies, and the agricultural sector plays an especially important role. Among larger states, Texas, North Carolina, and Illinois had relatively greater concentrations of agricultural degrees and certifications.

Post-secondary Institutions Prepare Graduates for Many Jobs That Are Unique to Agriculture

Not all the students completing agricultural-related degrees and certifications will find work in agriculture, just as agricultural employers will hire workers with degrees and certifications from different fields. The latter is especially true for occupations sought by employers throughout the economy (e.g., accountants, truck drivers, salespeople, manual laborers, etc.). However, many of the graduates completing degrees and certifications in the fields described above will fill occupations that are more unique to food and agriculture (e.g., agricultural equipment operators, large animal veterinarians, food scientists, etc.).

The distinction between these two types of occupations—those in-demand throughout the economy and those unique to food and agriculture—is an important one and filling these different types of occupations requires different strategies. Finding workers for more broadly sought occupations can pose real challenges for agricultural employers. For instance, recruiting information technology workers to work in agricultural enterprises and agricultural communities is a notable and recognized—but not fully understood—challenge facing the agricultural sector and can potentially hinder the advancement and usage of digital agriculture (Drewry, Shutske, Trechter, and Luck, 2022). In these instances, agricultural employers must effectively highlight the quality opportunities available in their industry and offer competitive compensation and benefits relative to other industries. By contrast, filling occupations that are more unique to food and agriculture requires longer-term career pathway strategies. This necessitates engaging students early through career exploration opportunities and then connecting them to specialized training and education to prepare them for these more specialized occupations (White, et al., 2020).

Albeit just a snapshot, the information presented above can help inform efforts intended to address the agricultural sector’s workforce needs. For instance, these data show where student interest lies in terms of program areas and how that interest has changed over time. These data also highlight the need to connect to both traditional educational partners like land grant institutions, but also to other important post-secondary institutions like community and technical colleges.

The next brief in this series will examine the characteristics (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity) of the students completing agricultural-related degrees and certifications and how those demographic characteristics vary by program area.

Notes

[1]These data are based on information provided by the nation’s public and private post-secondary institutions. These institutions submit an array of institutional data (e.g., enrollments, completers, student demographics) to the U.S. Department of Education and those data are subsequently organized and published in IPEDS.

[2]It should be noted that these data count awards (degrees and certifications) not people, so in some instances one person may receive multiple awards. The totals listed here include completers from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, as well as U.S. territories (e.g., Guam, U.S. Virgin Islands). The number of agricultural-related awards from U.S. territories was often small, but Puerto Rico is an exception. In 2021 Puerto Rico institutions awarded 981 agricultural-related degrees and certifications—a figure comparable to states like Michigan, Minnesota or Arizona.

[3] Completer data are organized by Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) codes. CIP codes organize completions by field of study. Similar to other data classification systems (e.g., NAICS), CIP codes are available at varying levels of aggregation. The 2-digit CIP code refers to a broad career field (e.g., 01-Agriculture/Animal/Plant/Veterinary Science and Related Sciences), the 4-digit CIP code refers to programs within a career field (e.g., 01.09-Animal Sciences), and the 6-digit CIP code refers to instructional awards (degrees and/or certificates) relating to a specific occupation or job title (e.g., 01.0905-Dairy Science). This analysis includes all the awards included within CIP 01, as well as agricultural education (CIP 13.1301) and agricultural engineering (CIP 14.03).

[4] This includes 1862 land grants, 1890 land grants (HBCUs), and 1994 land grants (tribal colleges and universities).

[5] It is important to note that the CIP classification system is periodically updated, often every decade. A significant change was made between the 2010 and 2020 CIP Codes, as programs related to veterinary studies (incl. veterinary sciences and veterinary/animal health technicians and technologies) were moved out of Health Professions and Related Programs (CIP 51) and into Agricultural/Animal/Plant/Veterinary Science and Related Fields (CIP 01). The program data presented here is based on the 2020 CIP codes, and crosswalks between the 2000 to 2010 CIP codes and 2010 to 2020 CIP codes were used to ensure a consistent time series. 2003 is the earliest year included because the 2000 CIP Codes were first implemented in the 2002 to 2003 data collection period.

[6] The relative concentration of these awards was measured by using location quotients (LQ). In this instance, these LQs measure ag-related awards as a share of total awards in a state, relative to ag-related awards as a share of total awards in the nation. An LQ of 1.0 means that the state has the same relative share of ag-related awards as the national overall. An LQ of 0.5 means that the percentage of ag-related awards in that state is half as great as the national share; an LQ of 2.0 means that the percentage of ag-related awards in that state is twice as large as the national share.

References

Charlton, D., Taylor, E.J., Vougioukas, S., and Rutledge, Z. “Innovations for a Shrinking Agricultural Workforce” Choices 34, no. 2 (Q2 2019): 1-8, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26785766.

Drewry, J., Shutske, J., Trechter, D., and Luck, B. “Assessment of Digital Technology Adoption and Access Barriers Among Agricultural Service Providers and Agricultural Extension Professionals’ Journal of the ASABE 65, no. 5 (2022): 1049-1059. https://doi.org/10.13031/ja.15018

Erickson, B., Fausti, S., Clay, D. and Clay, S. “Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities in the Precision Agriculture Workforce: An Industry Survey,” Natural Sciences Education 47, no. 1 (December 2018). https://doi.org/10.4195/nse2018.04.0010.

Hertz, T. and Zahniser, S. “Is There A Farm Labor Shortage?,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 95, no. 2 (January 2013): 476–81, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aas090.

Hetrick, R., Grieser, H., Sentz, R., Coffey, C. and Burrow, G. The Demographic Drought: The Approaching Labor Shortage. Prepared by Lightcast, April 2021. https://lightcast.io/resources/research/demographic-drought

McFadden, J., Njuki, E., and Griffin, T. Precision Agriculture in the Digital Era: Recent Adoption on U.S. Farms, EIB-248, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, February 2023. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/105894/eib-248.pdf

Stup, R., Ifft, J., and Maloney, T. The State of the Agricultural Workforce in New York, Prepared by Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management at Cornell University, March 2019. https://dyson.cornell.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2019/03/Cornell-Dyson-eb1901.pdf

White, M., Rahe, M., Milhollin, R., Horner, J., Russell, R., Presberry, R., and Kuhns, M. Workforce Needs Assessment of Missouri’s Food, Agriculture and Forestry Industries. Prepared by University of Missouri Extension, July 2020. https://extension.missouri.edu/media/wysiwyg/Extensiondata/Int/BusinessAndCommunity/Docs/WorkforceNeedsAssessment.pdf

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.