Farm Bill 2023: Questions About the Focus on SNAP Work Requirements

The effort to reauthorize the farm bill in 2023 is entangled with the debt ceiling debate, which includes demands for achieving spending reductions. Reports of the recent proposal by Speaker of the House, Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), indicate that one method being proposed to reduce spending involves work requirements on federal assistance to low-income households and individuals (Edmondson and Tankersley, April 17, 2023; Ferris and White, April 17, 2023; Duehren, April 17, 2023). This aligns with legislation previously introduced to tighten work requirements applicable to able-bodied adults for assistance from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (H.R. 1581; Hill and Downs, March 13, 2023).

Efforts to reduce SNAP program spending can create a critical impediment to reauthorizing a farm bill. Such was the experience for both the 2014 Farm Bill and the 2018 Farm Bill debates, where partisan disagreements over SNAP—including controversial changes to work requirements—caused problems for reauthorization in the House of Representatives. A returned focus on SNAP work requirements raises questions not only for farm bill reauthorization, but also about the policy itself particularly at a time of historic unemployment. This article briefly introduces these questions that may help add perspective about SNAP and provide context for the political debate.

SNAP Is the Primary Poverty Program in the Farm Bill

SNAP is by far the largest program in the Farm Bill. USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) reports that average monthly participation in the program during fiscal year (FY) 2022 was more than 41 million persons, and that the total costs of the program in FY2022 was more than $119 billion. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that SNAP spending will be above $115 billion per year throughout the ten-year baseline (farmdoc daily, February 23, 2023). SNAP spending accounts for more than 80% of the annual spending in a farm bill, which explains much of the political focus.

SNAP is a poverty program, and poverty metrics on a household basis determine eligibility for SNAP benefits. A household’s gross monthly income must be at, or below, 130% of the federal poverty level and the net income must be at 100% of the federal poverty level (7 U.S.C. §2014; CRS, October 4, 2022). Eligibility determinations also include asset tests and any earnings, as well as deductions for certain costs. Through categorical eligibility, households eligible to participate in other federal means-tested programs can also be eligible for SNAP. Finally, SNAP currently contains work requirements for eligibility, but those to a degree may vary by state. The program requires able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs) to meet work requirements (including accepting suitable job offers) or be in a training program and actively seeking employment. One area of controversy involves the ability of states to seek waivers from work requirements in areas with high unemployment rates (or those above 10%) or where there is a lack of jobs.

SNAP Participation Varies across the Country

Figure 1 shows the relative SNAP participation by state, as defined by the monthly average number of SNAP participants as a share of total population. The average monthly number of SNAP participants is reported by USDA (USDA, FNS, SNAP Tables) and the population estimates are drawn from the U.S. Census Bureau population estimates (Census Bureau, State Population Totals and Components of Change; Vintage 2022). In 2022, for example, the states with the highest relative SNAP participation were New Mexico (24.0%), Louisiana (18.0%), West Virginia (17.8%), and Oregon (17.4%); also, 21.5% of the District of Columbia’s total population received SNAP benefits. As context, an estimated 12.4% of the total U.S. population received SNAP benefits in 2022.

Poverty drives many of the differences in participation, as discussed further below, and indicates relative need. However, there are also differences in how states implement this federal safety net program. For instance, Edwards, Heflin, Mueser, Porter, and Weber (2016) compared SNAP caseloads in Oregon and Florida before, during, and after the Great Recession. They showed that while Florida sought to modernize the application process, it also maintained a six-month recertification process that could make participants vulnerable to disqualification. In addition, Florida did not undertake any formal outreach program to increase participation. The research found that eligible Floridians were less likely to be enrolled before the recession, and more likely to lose their benefits before, during, and after the recession. By contrast, Oregon pursued approaches intended to increase SNAP participation, such as outreach efforts, raising the income eligibility, and maintaining a 12-month recertification period. As a result, eligible participants remained in the program longer and income-eligible residents in Oregon were more likely to have been enrolled before the recession and keep their benefits during and after the recession. This analysis showed that these trends occurred independently of population characteristics or economic trends.

SNAP Participation Has Diverged from Unemployment Trends, Particularly since the Great Recession

As noted above, the debates about SNAP have initially focused on work requirements. However, SNAP is not an unemployment program, it is assistance to low-income households to purchase food. As a result, poverty determines eligibility, not employment. While employment status and poverty are obviously connected, it is also possible for employed people to still not earn enough income to be above poverty levels.

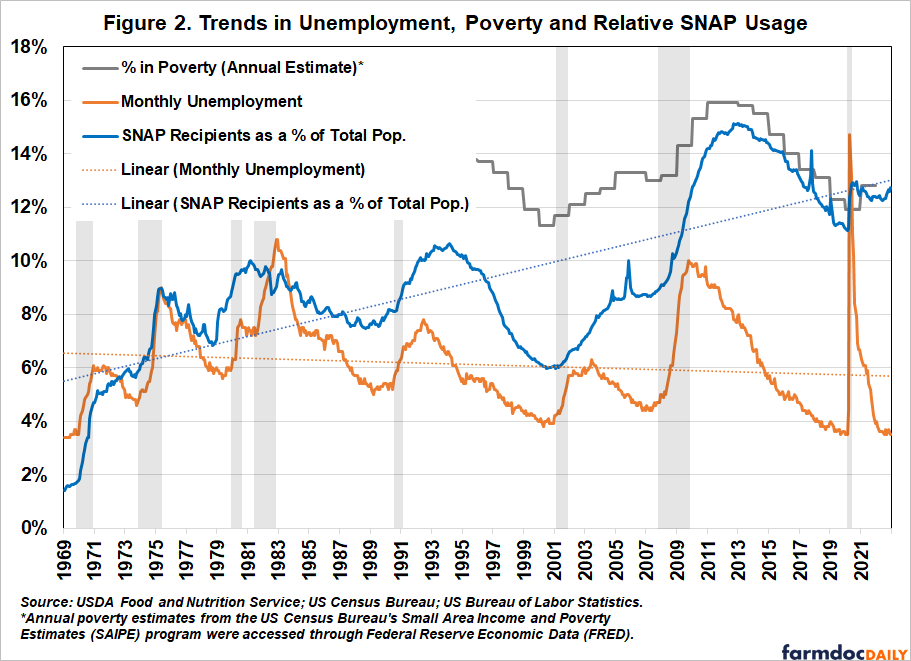

To these points, Figure 2 compares unemployment, SNAP participation, and poverty. As in Figure 1, SNAP participation is illustrated as the monthly average participants reported by USDA as a percentage of the population. Annual poverty estimates are from the Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) by the U.S. Census Bureau and published regularly since 1995, monthly unemployment data are produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and both data series were accessed through the St. Louis Federal Reserve’s Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) database.

Since the economic crisis and recession in 2008, SNAP participation and unemployment have diverged more so than in prior years (with the brief exception in the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic). During this period the share of the population using SNAP benefits has tracked consistently with the percent of people in poverty. This again highlights that SNAP participation is linked to poverty, not employment. Figure 2 also highlights that SNAP participation remains high at the same time unemployment is at historic lows. This raises questions about the effectiveness of changes to SNAP work requirements. Adding to these questions, USDA has reported that in FY2020 more than one quarter of SNAP households had earnings from work, and that four out of five SNAP households included a child, elderly or disabled person; USDA also reported that 81% of SNAP households had gross monthly income that was less than or equal to the poverty line (USDA, FNS, November 29, 2022).

Research has also found little evidence that SNAP work requirements achieve their intended goal of promoting employment and self-sufficiency. Such requirements often work to screen out adults and reduce overall caseloads, but have no effect on employment (Gray, Leive, Prager, Pukelis, and Zaki 2021). In fact, work requirements may further undermine the economic well-being of disadvantaged ABAWDs because they reduce the overall welfare benefits that they receive (Han, 2022). This in turn can lead to additional hardships by leading to poor nutrition and health outcomes (Ku, Brantley, and Pillai, 2019). If the goal is improving self-sufficiency, research has found that it is more effective to invest in programs that help ABAWDs overcome barriers to employment such as reliable transportation, lack of credentials, or a criminal record (Rowe, Brown, and Estes, 2017).

Concluding Thoughts

Going into a potential 2023 farm bill debate, the focus on SNAP and work requirements raises questions. Unemployment is currently at historic low levels, but SNAP participation remains at relatively elevated levels; similarly, poverty remains at relatively elevated levels. Trends for SNAP and unemployment have also diverged notably since the Great Recession in 2008. This divergence between employment and SNAP/poverty, itself, raises questions about the current state of the economy. At the very least, SNAP participation does not appear to impact employment nor serve as a disincentive to work.

This raises questions about the effectiveness of work requirements or similar policies, and scholarly research further magnifies these questions about work requirements. For a farm bill debate, the questions might be more pointed. Given low unemployment and elevated poverty, these questions include whether tightening work requirements can be expected to reduce SNAP spending. Given that the last two farm bill debates were nearly derailed by partisan disagreements over SNAP and work requirements, the questions also include whether a third round of this fight is worth the risk.

References

Aussenberg, Randy Alison and Gene Falk. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): A Primer on Eligibility and Benefits.” Congressional Research Service, CRS Report R42505, updated October 4, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/download/R/R42505/R42505.pdf/.

Coppess, J. "A View of the 2023 Farm Bill from the CBO Baseline." farmdoc daily (13):33, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, February 23, 2023.

Duehren, Andrew. “Kevin McCarthy Says House GOP Plans to Vote on Debt Limit, Spending Cuts.” The Wall Street Journal, April 17, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/mccarthy-says-house-gop-plans-to-vote-on-debt-limit-spending-cuts-cc39c0d8.

Edmondson, Catie and Jim Tankersley. “McCarthy Proposals One-Year Debt Ceiling Increase Tied to Spending Cuts.” The New York Times, April 17, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/17/us/politics/mccarthy-debt-ceiling-increase.html.

Edwards, M. Heflin, C., Mueser, P., Porter, S., and Weber, B. (2016) “The Great Recession and SNAP Caseloads: A Tale of Two States.” Journal of Poverty. 20(3): 261-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2015.1094770

Ferris, Sarah and Ben White. “McCarthy seeks to reassure Wall Street on stalled debt talks.” Politico.com, April 17, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/04/17/kevin-mccarthy-wall-street-debt-limit-00092324.

Gray, C., Leive, A., Prager, E., Pukelis, K. and Zaki, M. (2023) “Employed in a SNAP? The Impact of Work Requirements on Program Participation and Labor Supply.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 15(1): 306-341. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20200561

Han, Jeehoon. (2022) “The impact of SNAP work requirements on labor supply.” Labour Economics. 74:102089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2021.102089

Hill, Meredith Lee and Garrett Downs. “Republicans launch opening salvo against food aid.” Politico.com, March 13, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/03/13/republicans-snap-benefits-cuts-00086638.

Ku, L., Brantley, E., and Pillai, D. (2019) “The Effects of SNAP Work Requirements in Reducing Participation and Benefits From 2013 to 2017” American Journal of Public Health. 109(20): 1446-1451. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305232

Rowe, G., Brown, E., and Estes, B. (2017) “SNAP Employment and Training (E&T) Characteristics Study: Final Report.” Prepared by Mathematica Policy Research for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Policy Support,

Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2020,

by Kathryn Cronquist and Brett Eiffes. Project Officer, Kameron Burt. Alexandria, VA, 2022, available online, https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/characteristics-snap-households-fy-2020-and-early-months-covid-19-pandemic-characteristics.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.