The House Debt Ceiling Bill and the 2023 Farm Bill Reauthorization Debate

It could be that the first votes on any potential farm bill reauthorization in 2023 were taken on Wednesday, April 26, 2023, when the House of Representatives voted on legislation seeking to reduce federal spending and raise the debt limit (Carney, April 26, 2023; Romm, Sotomayor, and Caldwell, April 26, 2023; Edmondson and Hulse, April 26, 2023). Introduced by Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), the Limit, Save, and Grow Act of 2023 proposes changes in existing laws to reduce spending over ten years in return for raising the debt ceiling for one year (H.R. 2811). The political focus on reducing federal expenditures has substantial implications for the farm bill reauthorization process, among them the risks to all mandatory spending policies in the bill and reauthorization, itself. This article reviews the House debt limit bill and seeks to contribute some perspectives on farm policy.

Reviewing the Debt Ceiling Bill and SNAP

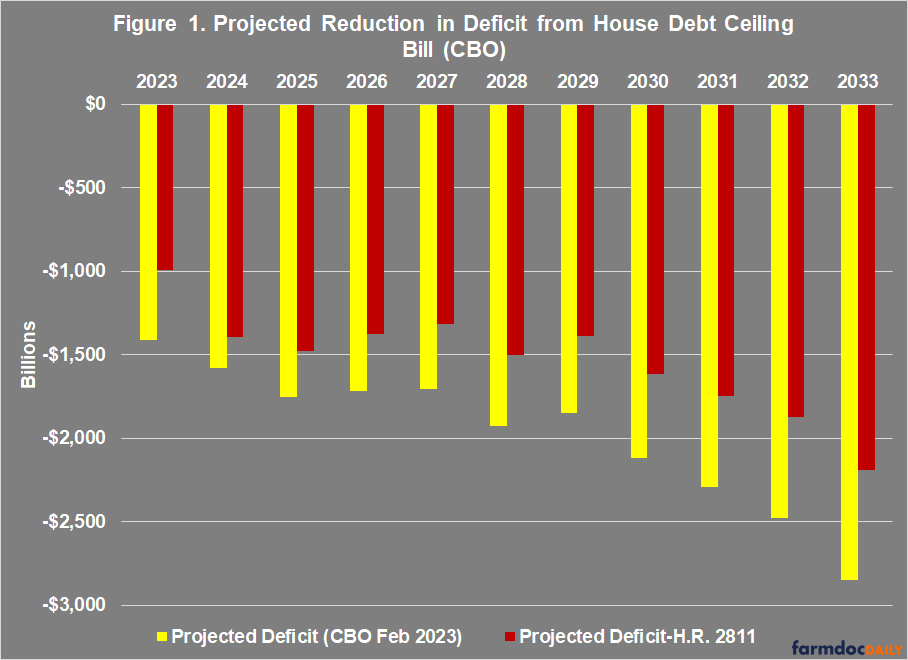

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the House bill would reduce the deficits for fiscal years (FY) 2023 through 2033 by $4.8 trillion; in February, CBO projected the total deficit from FY2023-2033 at $21.7 trillion (CBO, April 25, 2023; February 2023). Figure 1 illustrates the projected deficits from February and the changes in the deficit projected to result from the House bill. Note, however, negotiations over the bill’s provisions resulted in changes to the final bill agreed-to by the House. CBO estimated that rescinding some program spending would save an additional $9.6 billion, while restoring the tax credits applicable to renewable fuels would cost $38.6 billion; moving the date for SNAP work requirements a year earlier was not estimated to change the initial score (CBO, April 26, 2023). CBO’s projected deficit reductions in Figure 1 are lower than illustrated by roughly $29 billion in total over the entire period. Overall, if the House bill were enacted the total deficit would be approximately 79% of current projections. H.R. 2811 as it is currently written will not become law, however; the Senate is not expected to take it up and President Biden has said he would veto if it did pass Congress. One way to look at H.R.2811, therefore, is as the opening position of House Republicans in a more comprehensive negotiation.

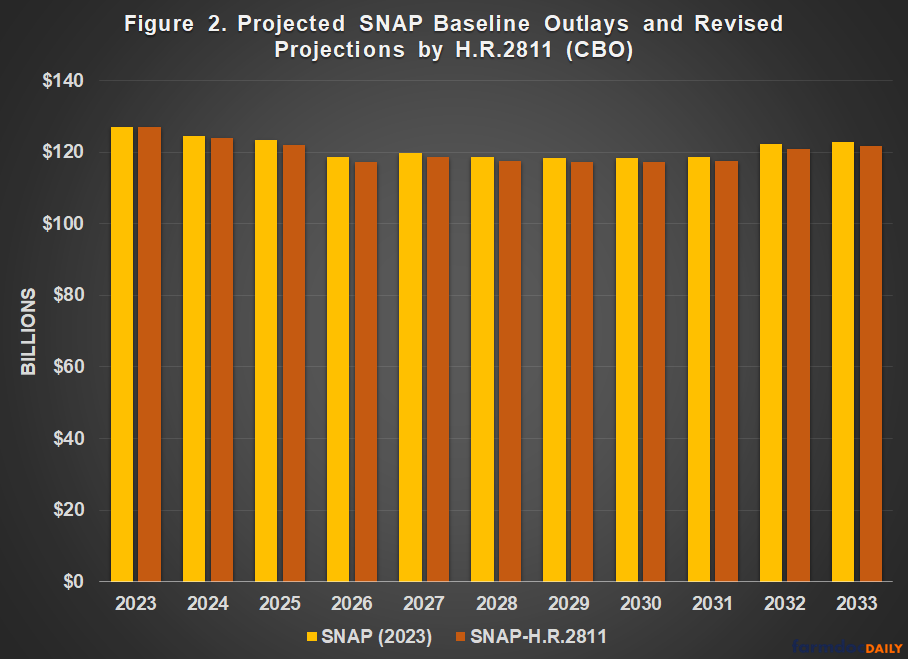

For a potential 2023 farm bill reauthorization, the critical provision in the House debt ceiling bill are those making changes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides assistance to low income households for purchasing food. Specifically, the House bill would revise the existing work requirements for SNAP benefits to able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWD), resulting in fewer people receiving assistance (see e.g., farmdoc daily, April 20, 2023; H.R. 2811). SNAP currently requires ABAWDs under 50 years of age to be employed or in a work training program for at least 80 hours per month, but permits states to waive the requirement for areas without sufficient jobs. This requirement applies for SNAP benefits beyond three months in a 36-month period. The House bill would increase the age provision to 55 years old and limit state exemption authority. CBO projected that the changes to work requirements would reduce spending in the program by $11.4 billion (FY2023-2033) and that 275,000 people would lose benefits each month, while 19,000 people would receive smaller benefits (CBO, April 25, 2023). H.R. 2811). Figure 2 compares the CBO projections for SNAP outlays in the February 2023 Baseline with the CBO projections as revised and reduced by H.R. 2811. In total, SNAP was projected to spend $1.3 trillion from FY2023 to FY2033 while the projected spending with the House bill changes would be 99% of the original baseline. The lack of significant spending reductions can likely be attributed to the relatively minor changes to the policy and current low levels of unemployment (see e.g., farmdoc daily, April 20, 2023).

Some Early Thoughts on Farm Bill Implications

If history is any guide, a political focus on reducing federal spending will substantially implicate and complicate farm bill reauthorization. The previous two farm bill reauthorization debates prove the point. A debt ceiling showdown in the summer of 2011 upended the farm bill reauthorization scheduled for 2012. Reauthorization was not enacted until February 2014, after the Senate had twice passed a bill (2012 and 2013) but the bill had initially been defeated on the House floor in 2013. Reauthorization scheduled for 2018 was not enacted until December of that year, after the House initially defeated the bill on the floor and the mid-term elections flipped control of the House from Republicans to Democrats. Partisan fights over SNAP were at the core of both difficult reauthorizations; House passage of H.R. 2811 signals a third consecutive iteration.

This recent history raises questions, and the troubled 2014 Farm Bill reauthorization effort provides an obvious analogue. The opening move in that effort turned out to be when House Republicans used the debt ceiling in 2011 to force negotiations over deficits and debt; the eleventh-hour compromise produced a joint super committee to achieve reductions that failed by November of that year, resulting in annual sequestration (Driessen and Labonte, December 29, 2015). When the House defeated the farm bill on the floor in June 2013, the catalyst for defeat were controversial changes to SNAP that CBO estimated would reduce spending by $39 billion from FY2014 to FY2023 and push an average of 2.8 million people out of the program, while also reducing benefits for 850,000 households; the SNAP baseline at the time was $764 billion and average monthly participation was projected to decline from 48 million (FY 2014) to 34 million (FY 2023) without the proposed changes (CBO, September 16, 2013); Lawrence, October 2015; Rosenbaum, Dean and Greenstein, September 17, 2013). The final enacted legislation was projected to reduce SNAP spending by $8 billion over FY2014 to 2023 (CBO, January 28, 2014). USDA reports that SNAP costs fell from $74 billion in FY2014 to $60 billion in FY2019 before spiking in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic (USDA, FNS, SNAP Tables: National Level Annual Summary).

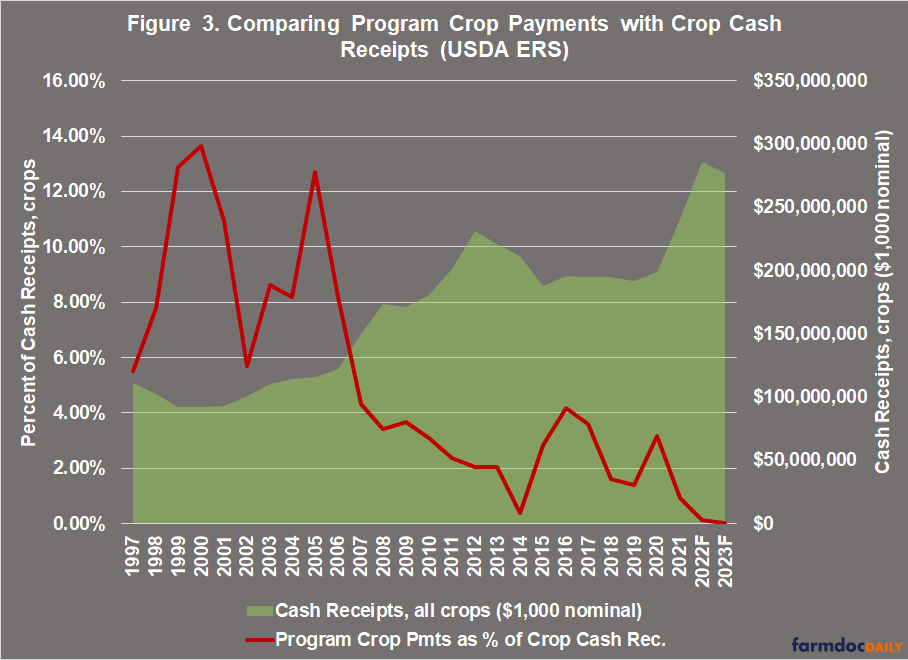

While SNAP is the largest program with mandatory spending in a farm bill, it is not the only one. One question that arises from what appears to be a third time around on this matter, is the impact on other mandatory programs. To begin with, Farm Bills also reauthorize direct program payments to farmers with base acres in Title I. Figure 3 compares total federal crop program payments[1] as a percent of total cash receipts for those program crops (green area) as reported by USDA’s Economic Research Service income and wealth statistics database, on a nominal basis, not adjusted for inflation (USDA, ERS, Farm Income and Wealth Statistics). To provide a more complete perspective, this calculation begins in 1997 after enactment of the landmark Federal Agricultural Improvement and Reform Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-127).

The national average by this measure since 1997 is 9.34% for crop program payments. Looking closer at the most recent era of farm programs, the map in Figure 4 presents the total crop program payments (ARC, PLC, LDP, and MLG) as a percent of crop cash receipts for those program crops by state since the 2014 Farm Bill (2015-2021 average). The national average of this measure is 4.3% for those years.

Figures 3 and 4 are intended as perspectives for further exploration and analysis. From this initial snapshot, a slight drop is detectable for crop programs: the national average from 2007 to 2013 was almost 4.8% as compared to 4.3% from 2015 to 2017. Any relationship to, or impacts from, the budget focus and debt ceiling is not immediately apparent. The results noticeably vary by state and region, however, especially for the crop program payments. There remains much for further exploration as this iteration unfolds.

Concluding Thoughts

The budget-driven political playbook may be an effective political strategy that is relatively easy to execute; it has been honed since 1981 (see e.g., Stockman 1986; Greider, December 1981). The policy accomplishments are much more difficult to discern, but this strategy has certainly accomplished little in terms of reducing federal spending, deficits or debt. The most recent House debt limit bill is a rather striking proposal, largely devoid of major substantive policy changes and would modestly reduce annual deficits or the national debt. The changes to SNAP stand as an exemplar, recycling work requirements at a time of historic unemployment achieves little actual savings while likely harming hundreds of thousands of low-income Americans. The point, however, is not policy substance or actual spending reductions; it is negotiating leverage and politics. The effectiveness of this latest iteration of the strategy remains very much in doubt, more so the consequences and impacts of either success or failure. The same can be said for the prospects of reauthorizing a farm bill in 2023. An optimist might see a proposal and an opening negotiating position less extreme than in the past, or that might have been expected; a pessimist might see a relatively transparent attempt at positioning for shifting the blame of pending catastrophe. The deadline for taking action is rapidly approaching.

Note

[1] The programs included are: Production Flexibility Contracts (PFC); Direct Payments (DP); Loan Deficiency Payments (LDP); Marketing Loan Gains (MLG); Counter-Cyclical Program (CCP); Average Crop Revenue Election (ACRE); Cotton Transition Assistance Payments (CTAP); Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC); and Price Loss Coverage (PLC).

References

Carney, Jordain. “House GOP passes its debt bill, upping pressure on Biden.” Politico.com, April 26, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/04/26/house-republicans-vote-debt-ceiling-00094078.

Congressional Budget Office. “H.R. 2642, Agricultural Act of 2014.” Cost Estimate, January 28, 2014, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/45049.

Congressional Budget Office. “Details About Baseline Projections for Selected Programs: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; February 2023.” https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2023-02/51312-2023-02-snap.pdf

Congressional Budget office. “CBO’s Estimate of the Budgetary Effects of H.R. 2811, the Limit, Save, Grow Act of 2023.” Cost Estimate, April 25, 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59102.

Congressional Budget Office. “CBO’s Estimate of the Budgetary Effects of Amendment 22 to H.R. 2811, the Limit, Save, Grow Act of 202[3].” Cost Estimate, April 26, 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59111.

Driessen, Grant A. and Marc Labonte. “The Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended: Budgetary Effects.” Congressional Research Service, CRS Report R42506, updated December 29, 2015, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/download/R/R42506/R42506.pdf/.

Edmondson, Catie and Carle Hulse. “House G.O.P. Passes Debt Limit Bill, Paving the Way for Clash with Biden,” The New York Times, April 26, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/26/us/politics/debt-limit-vote-republicans.html.

Greider, William. “The Education of David Stockman.” The Atlantic, December 1981, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1981/12/the-education-of-david-stockman/305760/.

Lawrence, Jill. “Profiles in negotiation: The 2014 farm and food stamp deal.” Brookings, October 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CEPMLawrenceFarmBill.pdf.

Romm, Tony, Marianna Sotomayor, and Leigh Ann Caldwell. “House passes GOP debt ceiling bill, as U.S. inches towards fiscal crisis.” The Washington Post, April 26, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/04/26/house-gop-debt-limit-debate/.

Rosenbaum, Dottie, Stacy Dean, and Robert Greenstein. “Cuts Contained in SNAP Bill Coming to the House Floor Would Affect Millions of Low-Income Americans.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 17, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/cuts-contained-in-snap-bill-coming-to-the-house-floor-would-affect-millions-of-low-income.

Stockman, David. The Triumph of Politics: How the Reagan Revolution Failed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1986).

Coppess, J. and M. White. "Farm Bill 2023: Questions About the Focus on SNAP Work Requirements." farmdoc daily (13):73, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 20, 2023.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.