The Incredible Shrinking of the Conservation Stewardship Program

History does not repeat but it certainly recycles, a process which can produce strange echoes across many years. Last week, the House of Representatives voted to remove the Speaker, leaving the chamber leaderless and unable to function (Mahtesian, October 11, 2023; Sotomayor et al., October 3, 2023). The procedural step was a vote on a Motion to Vacate the Speaker’s chair and it was the first time such a move had succeeded in House history. It was not the first time it had been used to deal with an intraparty fight in the chamber, however. In 1910, House Speaker Joseph G. Cannon (R-IL) faced a rebellion from within his caucus over his heavy-handed running of the chamber. He defeated a Motion to Vacate and, while the partisan repercussions rippled through the 1912 elections, the episode did little to diminish Cannon’s legacy; to this day, one of the House office buildings is named after him (see e.g., Brockell, October 3, 2023; Baker, 1973).

Public frustration with Congress echoes across 113 years; consider, for example, Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of the Forest Service and one of the founders of the conservation movement. In 1910, he vented frustration that, “[b]ecause the special interests are in politics, we as a Nation have lost confidence in Congress.” He was specifically concerned about special interest opposition to conservation and wrote, “[o]fficial opposition to the conservation movement, whatever damage it has done or still threatens to the public interest, has vastly strengthened the grasp of conservation upon the minds and consciences of our people” (Pinchot, 1910, at 132-34; Brown, 1999). Here again the echoes of history can be heard: farm bill reauthorization remains in serious doubt because of the turmoil and chaos in the House, but also faces challenges over conservation assistance to farmers (Abbott, October 11, 2023; Clayton, October 11, 2023; Johnson, October 12, 2023). As context, this article highlights some of the consequences of changes in policy design for conservation by reviewing the Conservation Stewardship Program.

Background

In a previous article, the impacts on spending projections for the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) were noted but not discussed (farmdoc daily, September 28, 2023). This article discusses further the changes in policy design and some of the consequences. As review, the 2008 Farm Bill created the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) out of the wreckage of the Conservation Security Program (P.L. 110-246). The earlier version had been enacted in the 2002 Farm Bill (P.L. 107-171). CSP was designed to be a green payments program similar to the annual direct payments program in Title I. A farmer qualified because they had implemented sufficient conservation on their farm; if qualified, the farmer enrolled in a five-year contract that made annual payments in return for improving or increasing conservation on the farm. After problems with implementation and funding plagued the 2002 version, Congress revised the program in 2008.

From a program cost and spending perspective, the key provision in the 2008 CSP was one that required USDA to enroll an additional 12.769 million acres each fiscal year, coupled with requiring the program to be managed to achieve a national average rate of $18 per acre. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) scored an increase of $4 billion from fiscal year 2008 to fiscal year 2017 for the entire conservation title (CBO, May 13, 2008). Notably, Congress reduced the acreage cap for the Conservation Reserve Program (from 39.2 million to 32 million), which would have reduced spending, and modestly increased funding for the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). Thus, a large portion of the additional spending in the title would have been for CSP.

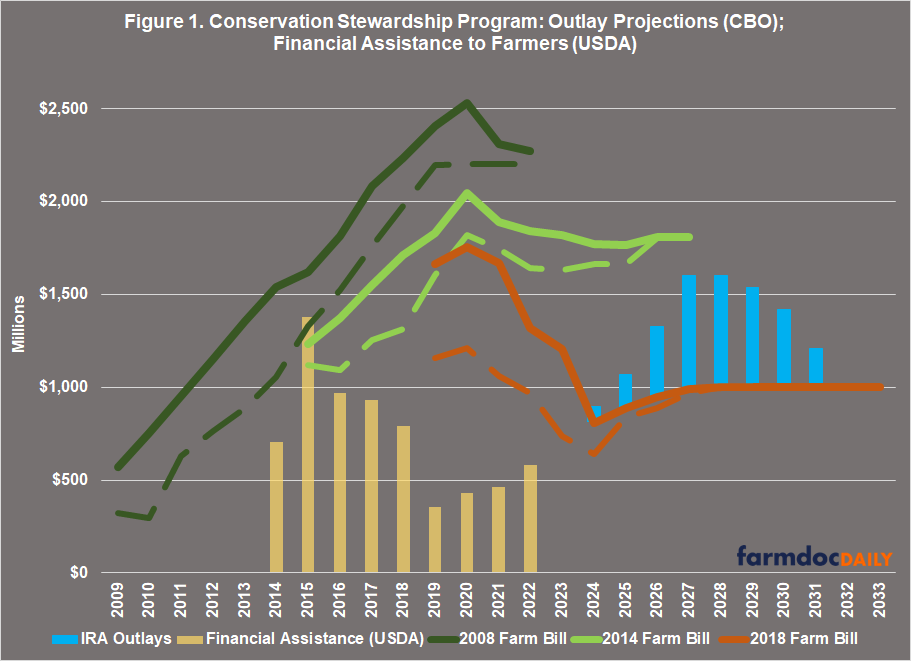

The 2008 Farm Bill proved to be CSP’s high water mark, funding has receded or shrunk since. Figure 1 compares the highest and lowest CBO outlay projections for CSP for the 2008 version (dark green), the 2014 version (light green), and the 2018 version (red). It is a revised version of Figure 1 contained in the earlier article. Added to this comparison, CBO’s May 2023 projections for CSP outlays from the additional funding provided by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 are included as blue bars above the baseline outlay projections. This represents additional funding for CSP above the baseline that is not part of the baseline. Finally, the total financial assistance (light yellow bars) as reported by the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) for FY2014 through FY2022 is also included (NRCS, Financial Assistance Program: Data Download).

Clear from Figure 1, the projections for payments to farmers from CSP have fallen substantially since the 2008 version of the program. As noted previously, the 2014 Farm Bill reduced the additional acres to be enrolled in the program from 12.769 million to 10 million per fiscal year (P.L. 113-79). But it was the 2018 Farm Bill that fundamentally changed CSP. Congress changed it from a program based on the acres enrolled (with annual increases) each fiscal year. After 2018, CSP was limited to a fixed amount of funding for the five-year contracts similar to EQIP (P.L. 115-334). From Figure 1, it appears that this change has not only shrunk spending projections for CSP but has also resulted in significant reductions in the financial assistance reaching farmers. The reduction in funding for CSP by the 2018 Farm Bill was so significant, in fact, that even the additional projected outlays from the Inflation Reduction Act fail to return the program to the 2014 projections.

Discussion

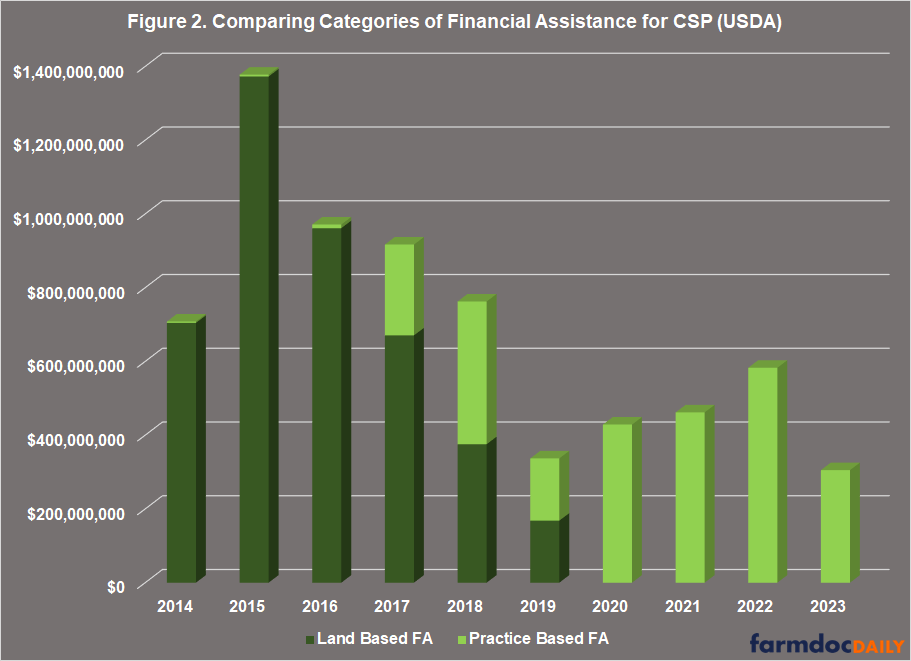

The primary reality for CSP is the financial assistance paid to those farmers adopting conservation and implementing stewardship on their farms. Figure 2 presents the total financial assistance to farmers as reported by NRCS but split into two categories representing the changes in CSP: (1) land based annual payments (dark green) for cropland, nonindustrial private forestland, pastureland, pastured cropland, and rangeland, which most closely represents the payments as designed in the 2014 Farm Bill; and (2) practice based (light green) using the NRCS practice codes used in EQIP, which most closely represents the 2018 redesign of the program that authorizes a fixed amount of funding. Admittedly, this categorical split does not align exactly with the policy designs in the two farm bills, but it is a close approximation. Figure 2 builds upon the data reported earlier through the Policy Design Lab project and the total columns equal those in Figure 1 (farmdoc daily, April 13, 2023; https://policydesignlab.ncsa.illinois.edu/eqip). Note also that the FY2023 data is likely incomplete.

Figure 2 further indicates that the shift from land-based financial assistance to practice-based after the 2018 Farm Bill has had drastic impacts on the conservation payments to farmers. In total, CSP paid out $2.6 billion more in financial assistance prior to the 2018 Farm Bill change, from FY2014 to FY2018. CSP has also paid out $1.65 billion more in total land-based financial assistance than in practice-based financial assistance. Note that NRCS reports land-based financial assistance for FY2014 through FY2019 and practice-based financial assistance for FY2014 through FY2023.

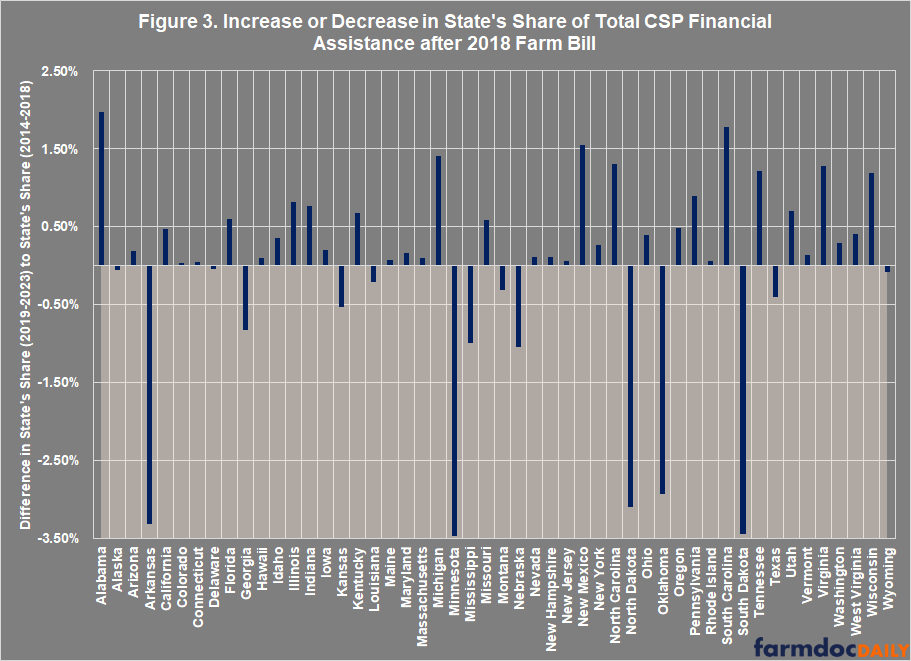

Figure 3 illustrates the changes in each State’s share of CSP financial assistance by subtracting the State’s share of total financial assistance under the 2018 Farm Bill (FY2019-FY2023) from the State’s share under the 2014 Farm Bill (FY2014-FY2018). The change to CSP in the 2018 Farm Bill not only appears to have decreased financial assistance to farmers but also appears to have had very different impacts among the States. For example, the share of total financial assistance that was paid to farmers in Arkansas decreased by -3.32%, falling from 7.98% of the total from FY2014 to FY2018 to 4.66% of the total from FY2019 to FY2023. The other states with large decreases between the two were Minnesota (-3.47%), North Dakota (-3.09%), Oklahoma (-2.93%), and South Dakota (-3.45%). By comparison, Alabama increased its share of the national total going from 0.66% in FY2014-FY2018 to 2.63% in the later years (difference of 1.97%), as did South Carolina (1.78%). Illinois improved from 3.79% of the national total for FY2014-FY2018 to 4.79% for FY2019-FY2023 (0.82%).

Figure 4 provides an interactive map comparing the state performances for the different versions of CSP. It presents the ratio of total financial assistance received by farmers in the State from FY2014 to FY2018 (the 2014 Farm Bill) to that received from FY2019 to FY2023 (the 2018 Farm Bill). Hovering over each State will also provide the ratio between land-based financial assistance to practice-based financial assistance, as well as the State’s share of each category. For example, Minnesota’s ratio is 4.1 for the total financial assistance from FY2014 to FY2018 ($364.5 million) compared to the total financial assistance from FY2019 to FY2023 ($89 million). Minnesota also fared better under land-based assistance compared to practice-based with a ratio of 2.6; farmers received $326 million total for the former compared to $127.5 million for the latter.

Looking further at Minnesota’s performance with CSP financial assistance, the State received a larger share of the total from FY2014 to FY2018 (7.69%) than from FY2019 to FY2023 (4.22%). Additionally, Minnesota’s share of total financial assistance for land-based practices (7.67%) was greater than its share of practice-based assistance (4.9%). Illinois improved in the overall ratio from the 2014 version (FY2014-FY2018) to the 2018 version (FY2019-FY2023) with a ratio of 1.9, and its land-based to practice-based ratio was 1.7; similarly, Illinois farmers received 3.97% of the national funding for FY2014-FY2018 and 4.79% of the national funding for FY2019-FY2023, but fell from 4.32% of the national funding for land-based assistance to 4.07% for practice-based.

Concluding Thoughts

The words of the statute put policies in action and changes in those statutory terms can alter the impacts of policies. The Conservation Stewardship Program provides a useful case study because Congress has made significant changes to the program in each previous farm bill since it was first enacted in 2002. Congress has not substantively changed the policy of providing farmers with annual contract payments for working lands conservation practices and natural resource stewardship on their farms, however. The most drastic changes to the program authorization were in the 2018 Farm Bill. Congress changed the program from land-based (with increasing acreage enrollments) financial assistance to practice-based (with a fixed amount of funding available). The consequences of these changes show up in the bottom line: projections for spending on CSP have fallen substantially and the reported levels of financial assistance have also decreased. Most notably, the impacts of these changes were not distributed equally among the States and may have complicated program operation in multiple ways, all of which raises questions for further exploration.

Former Chairman of the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry Tom Harkin (D-IA) argued that farm policy should reward farmers who were actual stewards of the land and natural resources. As one example, he told the Senate that it was “abundantly clear that conservation on working lands needed to be addressed” and that Congress “needed a conservation program that rewarded those committed stewards of the land, instead of excluding them . . . a program to secure the right of all American farmers and ranchers to access conservation dollars to adopt and maintain conservation practices . . . a monumental step forward toward truly addressing conservation of natural resources on our farms and ranches” (Congressional Record, February 13, 2003, at 4026-28). Chairman Harkin had to fight to get the program included in the 2002 Farm Bill program, only to lose fights with appropriators who cut the program’s spending before USDA began operating it (a story worth further review in its own right). After four authorizations and 20 years of operation, Chairman Harkin’s vision for rewarding farmers who conserve natural resources has been severely curtailed and many continue to be excluded. Congress has repeatedly chosen to shrink the CSP program to an incredible degree and with serious consequences. Consider that CBO had once projected that assistance to farmers for conservation stewardship would peak in fiscal year 2020 at $2.5 billion but NRCS reported only $429 million in FY2020, just 17% of the projection. In fiscal year 2022, the financial assistance ($563 million) was a quarter of the earlier projections ($2.2 billion); from fiscal years 2015 to 2022, moreover, the assistance to farmers has been more than $11 billion less than the promise of CSP as projected in 2009. The incredible shrinking of CSP begs many a question but offers few answers, it may also serve as a warning. If a farm bill reauthorization can make it through the chaos of the current Congress, the questions raised herein might be debated and provide a test of Gifford Pinchot’s 113-year old argument.

References

Abbott, Chuck. “Vilsack encourages congressional creativity to break farm bill impasse.” Fern’s Ag Insider, thefern.org. October 11, 2023. https://thefern.org/ag_insider/vilsack-encourages-congressional-creativity-to-break-farm-bill-impasse/.

Baker, John D. “The Character of the Congressional Revolution of 1910.” The Journal of American History 60, no. 3 (1973): 679-691. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1917684.

Brockell, Gillian. “The last vote to remove a House speaker backfired on the GOP.” The Washington Post. October 3, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/10/03/joseph-cannon-speaker-motion-vacate/.

Brown, Susan Jane M. “The Forest Must Come First: Gifford Pinchot's Conservation Ethic and the Gifford Pinchot National Forest-the Ideal and the Reality.” Fordham Envtl. LJ 11 (1999): 137.

Clayton, Chris. “Farm Bill Extension Likely Needed.” DTNProgressiveFarmer.com. October 11, 2023. https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/news/article/2023/10/11/vilsack-calls-farm-bill-extension.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023: NRCS Backlogs and the Conservation Bardo." farmdoc daily (13):177, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 28, 2023.

Coppess, J. and A. Knepp. "A View of the Farm Bill Through Policy Design, Part 1: EQIP." farmdoc daily (13):69, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 13, 2023.

Johnson, Wendy. “Op-ed: Farmers Want Climate Resilience, but GOP Lawmakers Want to Redirect Billions in Conservation Funds.” CivilEats.com. October 12, 2023. https://civileats.com/2023/10/12/op-ed-farmers-want-climate-resilience-but-gop-lawmakers-want-to-redirect-billions-in-conservation-funds/.

Mahtesian, Charlie. “The House gets a new speaker. Maybe.” Politico.com. October 11, 2023. https://www.politico.com/newsletters/politico-nightly.

Pinchot, Gifford. 1910. “The Fight for Conservation” in The Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850-1920. The Library of Congress, available online: https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/consrv:@field(DOCID+@lit(amrvgvg11div15)). Or: https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amrvhtml/conshome.html.

Sotomayor, Marianna, Leigh Ann Caldwell, Amy B. Wang, Paul Kane, and Mariana Alfaro. “Kevin McCarthy removed as House speaker in unprecedented vote.” The Washington Post. October 3, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/10/03/kevin-mccarthy-house-speaker-vote-motion-to-vacate/.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.