Farm Bill 2023: Is There Bad Medicine in Base Acres and Reference Prices?

During debate on the Farm Bill in 1956, Senator Clinton Anderson (D-NM), who had been Secretary of Agriculture in the Truman Administration, argued against continuation of the New Deal era parity farm support policy that combined price supports with acreage controls. Senator Anderson stated that continuing the policy was akin to trying to “help the farmer by giving him another dose of the medicine that has made him sick” (Congressional Record, March 9, 1956, at 4288). Senator Anderson’s admonition echoes through farm policy and remains relevant to this day. At its core, the question seeks to understand whether farm policies are doing more harm to the actual farmer than good. This article explores one aspect of this question, asking whether base acres and reference prices increase or inflate cash rents. Cash rent data has been recently updated by USDA, showing that cash rents continue to increase and that Illinois is the most expensive state in the Corn Belt for cash rent with 9 of the top 10 most expensive counties for cash rent (Payne, August 29, 2023; August 8, 2023). The discussion adds further perspective to previous discussions on farm policy, while also recognizing that further analysis is needed (farmdoc daily, June 29, 2023; July 20, 2023; August 3, 2023; August 10, 2023; August 17, 2023; August 24, 2023).

Background

In summary, the major farm payment programs (Agriculture Risk Coverage, ARC and Price Loss Coverage, PLC) provide direct cash payments to farmers with historic records of planted acres known as base acres. The use of base acres decouples the payments from actual planting and production decisions, allowing farmers to plant crops without regard to potential federal payments. Reference prices are established by Congress and fixed in the statute; they do not change. This is a critical feature for this discussion. The ARC program uses a five-year Olympic moving average of prices and yields, which adjusts slowly with changes in the market. ARC does, however, include the effective reference price as the floor in the five-year Olympic moving average price calculation (in any year in which the marketing year average (MYA) is below the effective reference price, the effective reference price replaces the MYA). By comparison, the statutory reference price has a much more prominent role in PLC payments: payments are triggered in any year in which the MYA is below the effective reference price, which is the higher of the statutory reference price or the five-year Olympic moving average of MYA prices. In both programs, the statutory reference price establishes a price floor in the program calculations, but it is somewhat moderated by the ARC calculations.

As further background, previous research has found some level of connection between federal payments and land prices or cash rents (see e.g., Ifft, Kuethe, and Morehart, 2015; Kirwan and Roberts 2016; Hendricks, Janzen, and Dhvetter, 2012; Ciaian, 2021). The general conclusion of these studies is that farm program payments impact cash rents; for every dollar paid to operator tenants, research has found that the landlord receives between 20 to 80 cents depending on the population studied. Most relevant to the question discussed below, the research has found that the easier these payments are to anticipate—the more certain or more known and expected—the easier it is for landowners to expect the payments and take them into account with rent decisions. Intuitively, it would also factor into the farmer’s decisions to compete for cash rents; payment expectations likely provide support for offering higher cash rents, further feeding inflationary pressures in the area. Generally, ARC and PLC payments are contingent payments as opposed to annual direct payments and could be difficult to predict. That is not true for all covered commodities, however, and the predictability of payments depends to a significant degree on the levels Congress establishes the statutory reference price for a program crop relative to market prices. The higher the statutory reference price, the more likely it will trigger large payments. As such, some program crops such as cotton, rice and peanuts have high statutory reference prices relative to market prices and payments are more dependable. The expectations for payments would be easier to factor into cash rents, holding them higher even when prices decline and fueling future rent increases.

Discussion

USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) calculates an “opportunity cost of land” and reports it as part of the costs and returns data (USDA-ERS, Commodities Costs and Returns, updated August 2, 2023). ERS explains that the value of land depends on the crops or livestock produced as reflected in rental costs and it reports the opportunity cost of land using cash rental rates unless cash rental markets are too thin (USDA-ERS, Documentation). The discussion uses the terms cash rent and opportunity cost of land interchangeably, and the national average (or U.S. total) amounts are used as reported by ERS.

(1) A Closer Look at Cash Rent (Opportunity Cost of Land)

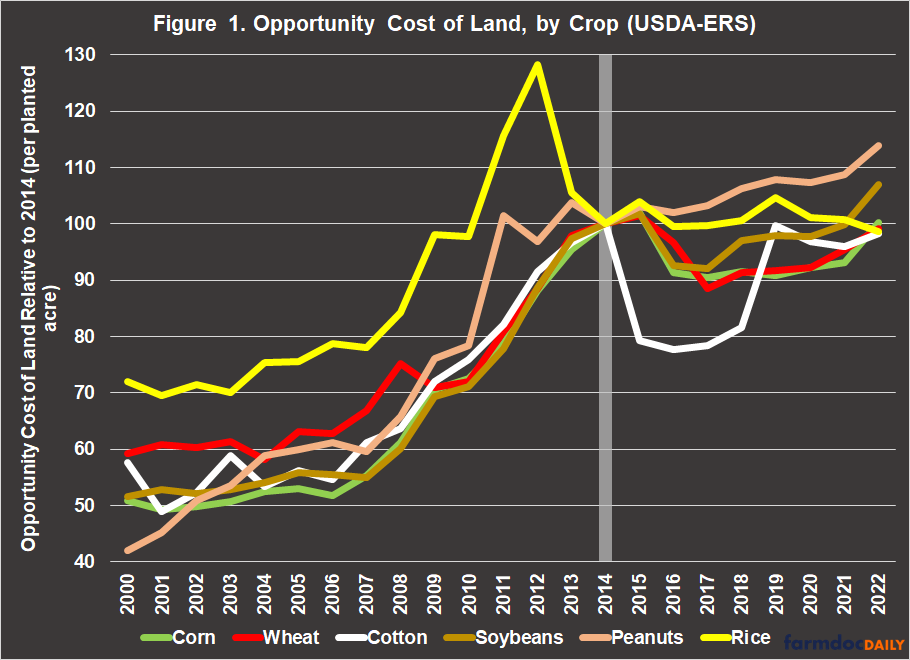

To begin the discussion, Figure 1 illustrates the opportunity cost of land or cash rent per acre planted for each of the major program crops from 2000 to 2022 using the cost and return data reported by ERS. Figure 1 uses 2014 as the base year (2014=100) and each year’s cash rent is compared to it. Each year’s cash rent is normalized to the year 2014 to make it clear how cash rent has changed for each crop relative to the 2014 Farm Bill. In Figure 1, cash rents show a steady increase each year to 2014 for all crops, although rice cash rents trended higher and experienced a much more significant spike in 2012 as compared to 2014.

The cash rent for cotton is a clear outlier in Figure 1. Prior to 2014, it largely follows the other major program crops’ upward trajectory. The year after the 2014 Farm Bill went into effect, cotton cash rents dropped about 20% (hitting a level of 80 in 2015 compared to 100 in 2014) while the cash rents for other program crops in 2015 barely increased from their 2014 level.

The Agriculture Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-79) removed upland cotton from the ARC and PLC programs as a result of the U.S. attempt to resolve the World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute with Brazil over cotton subsidies. The WTO ruled against U.S. cotton subsidies and permitted retaliation by Brazil against U.S. exports; however, the two countries negotiated a settlement to avoid the consequences of retaliation and that settlement included ending farm bill cotton subsidies. In 2014, Congress eliminated upland cotton base acres, shifting them into generic base acres, and upland cotton was not included in the covered commodities definition for ARC and PLC. Although the former cotton base (generic base) did receive temporary cotton transition assistance payments (CTAP), cotton did not have a reference price and was not eligible for ARC or PLC Payments. This was in addition to the general shift in farm policy in the 2014 Farm Bill, in which Congress eliminated the annual direct farm payments and replaced them with the contingent payments through either ARC or PLC.

(2) A Cotton Case Study in the Impacts of Program Base and Payments on Cash Rents

Cotton cash rents abruptly returned to their 2014 level in 2019; importantly, this was the year the 2018 Farm Bill went into effect after having been enacted on December 20, 2018. In 2018, Congress added “seed cotton” as a covered commodity and permitted farm owners the option to allocate generic base acres as base acres of seed cotton. Congress also established a seed cotton statutory reference price. These changes were then reauthorized by Congress in the 2018 Farm Bill, effectively returning cotton to the ARC and PLC programs (Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018, P.L. 115-334). The changes in cash rents for cotton acres are noticeable in Figure 1 and correspond to the unique changes for cotton support policy. No other program crop experienced this sudden fall and immediate rise coinciding with the two Farm Bills.

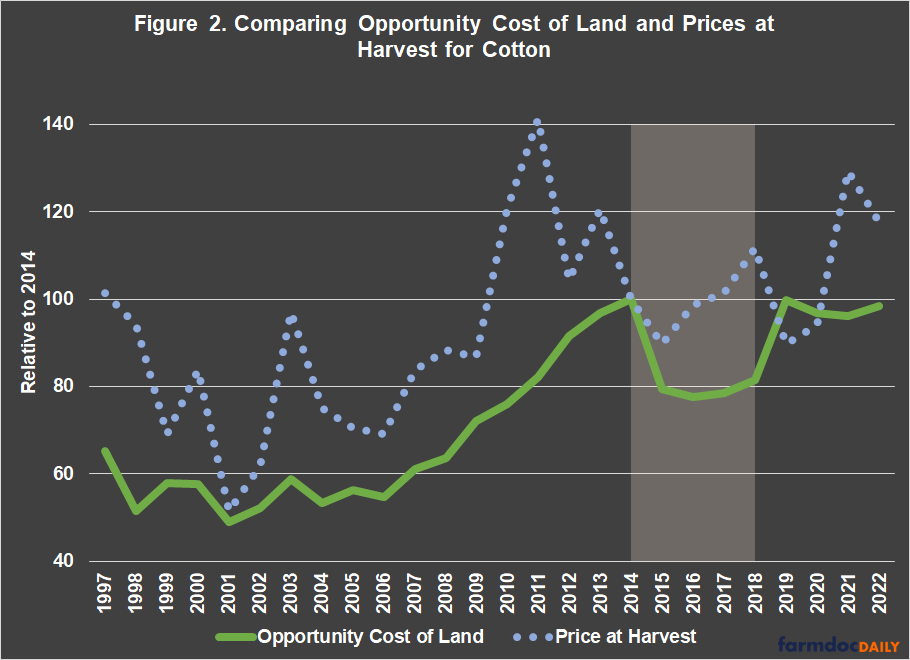

Of course, cash rents are also impacted by crop prices not just government payments. However, fluctuations in cotton price do not seem to explain the sudden drop between the 2014 and 2018 Farm Bills. Figure 2 illustrates the average cotton price at harvest and the opportunity cost of land reported by ERS. As in Figure 1, Figure 2 uses 2014 as the base year (2014=100) and each year’s price and opportunity cost is compared to 2014. The years 2014 through 2018 are highlighted and there is a clear divergence between prices and cash rents after the initial drop in 2014; cotton prices rebounded, but cash rents did not rebound until after the policy changes in 2018. Cotton’s cash rent rebounds relative to 2014 only after seed cotton is created by Congress and provided base acres and a reference price.

(3) Comparing Cotton Cash Rents to Rice and Peanuts

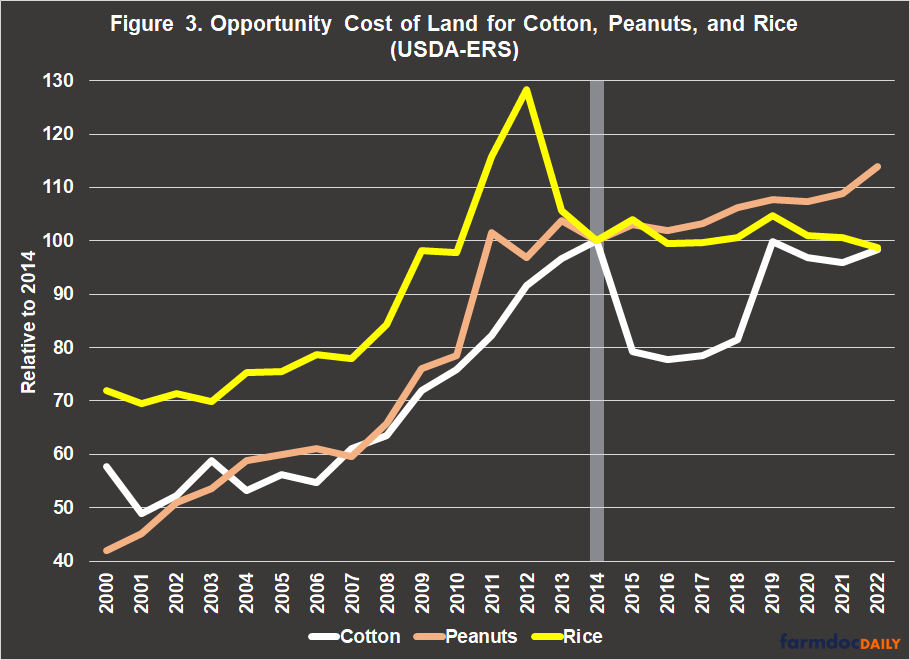

Figure 2 on its own does not provide definitive proof of the impact of base acres and reference prices on cash rents, but it certainly presents strong evidence. Exploring this question further, Figure 3 illustrates the opportunity costs of land for cotton, peanuts, and rice from 2000 to 2022 with 2014 as the base year (2014=100) and all years are relative to it. This again illustrates how much of an outlier cotton cash rents were compared to the other major southern commodities. Rice and peanut cash rents either stay the same or increase from 2014 onward, even while cotton temporarily drops off. While further analysis is needed, the comparisons in Figure 3 do not appear to support an argument that changes in Southern land markets can help explain why cotton cash rents temporarily dropped between the last two farm bills.

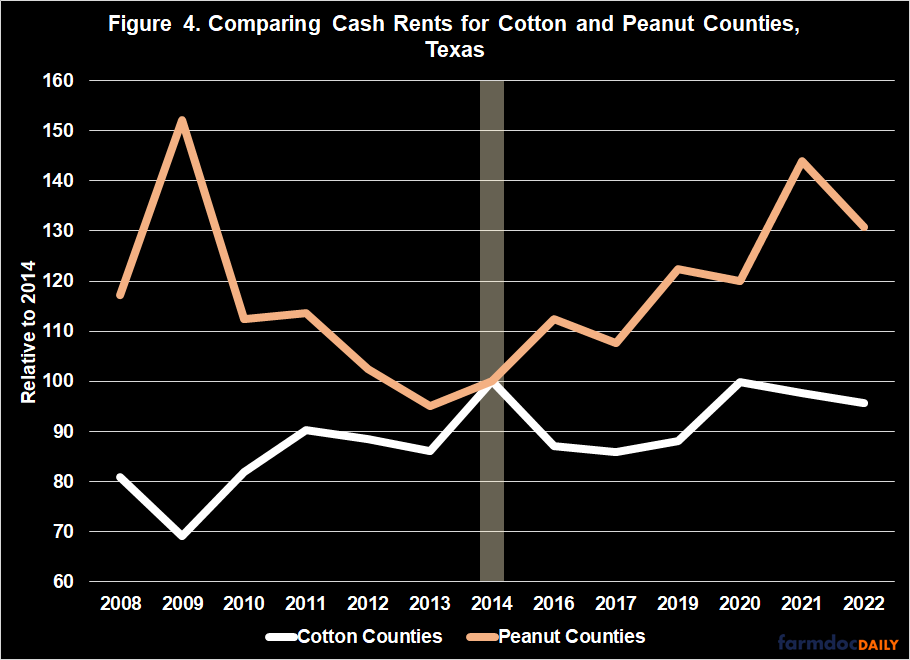

Figure 4 presents one further comparison for consideration, that of the different trajectories for cotton and peanuts in Texas after the 2014 Farm Bill. Figure 4 uses the cash rent survey data reported by USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) at the county level (USDA-NASS, Surveys: Cash Rent). Among other things, this is the cash rent data that FSA uses to calculate the rental rates for the Conservation Reserve Program. The cotton counties in Figure 4 are those with at least 50% of the county’s total base acres in seed cotton base in 2019 and the average cash rent for all such counties is illustrated. The peanut counties are those with at least 25% of total base acres in peanut base but less than 50% in seed cotton base in 2019, with the average cash rents for all peanut counties. Each of these are compared relative to their 2014 levels.

Here again, Figure 4 supports a conclusion that farm program payments and base acres have a noticeable impact on cash rents. The average cash rent in all cotton counties follows a similar pattern as previously illustrated, falling after the 2014 Farm Bill removed cotton base from ARC and PLC and rebounding after seed cotton was added to the programs. Figure 4 also highlights the extent of increased cash rents in peanut counties after Congress established the high relative reference price for PLC payments on peanut base acres. Additional analysis of cash rents in similar counties could further demonstrate the impact of reference prices and base acres on this critical cost to farmers.

Concluding Thoughts

While not definitive, there is much in this discussion for concern about the impact on cash rents of base acres and statutory reference prices that are high relative to market prices. These concerns apply to policy decisions that continue high reference prices but could be magnified by policy decisions that increase reference prices. The impacts discussed also align with previous research that the more predictable and expected a farm payment is, the more likely the payment will factor into cash rents—either from the landlord, or the farmers as they compete for leased acres. At the very least, the findings in this discussion and those of previous research should give reason to pause the push for higher reference prices, dig into the issue deeper, and reconsider the design of PLC. For researchers, there appears to be significant areas of further research with the potential to provide valuable explanations about the impacts and the potential unintended consequences of this policy.

As indicated in the opening quote by Senator Clinton Anderson in 1956, the concerns raised by this discussion are not new, neither is the potential that farm policy payments could serve up problematic doses of bad medicine to the very farmers they are ostensibly designed to help. Willard Cochrane pioneered the concept of a treadmill for farmers, memorably arguing that things that appear good for farmers in the short-run—such as technological progress, increased efficiency, and government subsidies—can ultimately work to do harm and price those same farmers out of the market (see e.g., Cochrane, 1979; Herdt and Cochrane, 1966). Government payments, he argued in “The Treadmill Revisited,” can actually work against farmers (Levins and Cochrane, 1996). The more government payments become certain, the more they will factor into land value and cash rent. While landowners benefit from their land increasing in value, operators renting land will see their costs increase. Cochrane argued that these impacts of the payments counter any benefits to the farmer from the government payments. For this reason, increasing government payments may benefit farmers in the short-term but hurt them over the long term.

Finally, and maybe most importantly, Cochrane also warned that, should the cycle continue, the barriers to entry for agriculture would become higher and higher. Government payments could fuel land price inflation that further prices beginning farmers out of the market. What is bad medicine for the established farmer could become something much worse for the young and beginning farmer. They could be priced out of the cash rent market while at the same time not likely receiving the subsidies fueling the problem. Without the next generations of farmers, the future of American agriculture will be dire indeed. This is a problem that no amount of reference price increase in 2023 will help. These are matters that should weigh heavily on the Congressional mind as reauthorization of these policies is undertaken.

References

Ciaian, Pavel, Edoardo Baldoni, d'Artis Kancs, and Dušan Drabik. “The Capitalization of Agricultural Subsidies into Land Prices.” Annual Review of Resource Economics 13 (2021): 17-38. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-resource-102020-100625

Cochrane, Willard. The Development of American Agriculture: A Historical Analysis, Second Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1979, reprinted 1993).

Coppess, J. "A View of the Farm Bill Through Policy Design, Part 4: ARC and PLC." farmdoc daily (13):156, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 24, 2023.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023: Another Perspective on Reference Prices and Base Acres." farmdoc daily (13):152, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 17, 2023.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023: The Intersection of Base Acres and Reference Prices." farmdoc daily (13):147, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 10, 2023.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023: Planted Acres and Additional Pieces of the Base Acres Puzzle." farmdoc daily (13):143, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 3, 2023.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023: Reviewing Pieces of the Base Acres Puzzle." farmdoc daily (13):134, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 20, 2023.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023 and Policy Design: Another View of ARC-CO and PLC." farmdoc daily (13):119, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 29, 2023.

Hendricks, Nathan P., Joseph P. Janzen, and Kevin C. Dhuyvetter. “Subsidy Incidence and Inertia in Farmland Rental Markets: Estimates from a Dynamic Panel.” Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics (2012): 361-378. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/23496722.pdf

Herdt, Robert W., and Willard W. Cochrane. “Farm Land Prices and Farm Technological Advance.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 48, no. 2 (1966): 243-263.

Ifft, Jennifer, Todd Kuethe, and Mitch Morehart. “The Impact of Decoupled Payments on US Cropland Values.” Agricultural Economics 46, no. 5 (2015): 643-652. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/agec.12160.

Kirwan, Barrett E. “The Incidence of US Agricultural Subsidies on Farmland Rental Rates.” Journal of Political Economy 117, no. 1 (2009): 138-164. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/598688

Levins, Richard A., and Willard W. Cochrane. “The Treadmill Revisited.” Land Economics 72, no. 4 (1996): 550-553.

Payne, Susan. “Top 10 Highest Cash Rents by County.” DTNProgressiveFarmer. August 29, 2023. https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/news/business-inputs/article/2023/08/29/top-10-cash-rent-averages-county.

Payne, Susan. “USDA Cash Rent, Land Value Numbers Released.” DTNProgressiveFarmer. August 8, 2023. https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/news/business-inputs/article/2023/08/08/usda-releases-cash-rent-average-land.

Roberts, Michael J., Barrett Kirwan, and Jeffrey Hopkins. “The Incidence of Government Program Payments on Agricultural Land Rents: The Challenges of Identification.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 85, no. 3 (2003): 762-769. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1093/ajae/aaw022

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.