Conservation Quandaries, Part 3: Reviewing Practice Standards for Irrigation Practices

As discussed previously, water laws in western states arguably pose the second greatest challenge or quandary for conservation policy (farmdoc daily, February 27, 2025). This quandary is magnified by that of stretching limited funding across too many programs and practices because state water laws may limit the effectiveness of conservation policies, or worse. This article adds to the discussion by reviewing the practice standards for the irrigation practices that receive the most financial assistance from the Environmental Quality Incentives Program.

Background

The Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) includes among its purposes the conservation of surface and ground water (16 U.S.C. §3839aa). Problems arise when this purpose collides with water laws. The problems are most acute with respect to the prior appropriations and related systems of water laws in most western states. In general, these laws provide for a quasi-property right in the use of an amount of water from a source. The right is based on timing of the diversion of water for beneficial use and operates on a priority of rights (“first in time, first in right”) system. More problematically, such rights also present potential penalties for reducing use (“use it or lose it”) such as through conservation and efficiency (farmdoc daily, February 27, 2025; F. Arthur Stone & Sons v. Gibson, 630 P.2d 1164, 1168-69 (KS 1981); Colo. River Water Conservation Dist. v. United States, 424 U.S. 800, 805 (1976)).

The challenges inherent in these systems have been discussed at length. For example, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), in its review of NRCS conservation programs for irrigation, found that efficient irrigation practices may not reduce water consumption if “farmers subsequently expand their irrigated cropland” or increase water-intensive crop production (U.S. GAO, GAO-20-128SP, November 12, 2019, at 68-69). Research on irrigation water usage and conservation efforts consistently encounters the same challenges for water resources, often proclaiming a paradox but not always connecting the problem to water laws (see e.g., Lankford, 2023; Grafton et al., August 24, 2018; Li and Zhao, 2018; Sears et al., 2018; Wallender, 2017; Khanna and Zilberman, 2017; Pfeiffer and Lin, 2014; Pfeiffer and Lin, 2012; Schaible and Aillery, 2012; Wallender and Hand, 2011; see also, Frisvold, 2024). The implications for policy—especially for conservation policies with limited funding available, such as EQIP—are substantial. Every dollar spent on irrigation practices is a dollar not spent on other natural resource concerns and conservation priorities. The matter is worsened if those irrigation dollars have the opposite effect and result in more water consumed.

Discussion

As reported by NRCS, the total financial assistance provided by EQIP for irrigation (or related) practices from FY2014 to FY2023 in the U.S. exceeded $3.3 billion (NRCS Data Viewer, “NRCS Financial Assistance Program Data”). Note that this review is limited to the funds obligated through the Farm Bill authorization (e.g., Commodity Credit Corporation) and not the Inflation Reduction Act. The top five irrigation practices in these years were: sprinkler systems (27.5%); irrigation pipelines (23.4%); irrigation system-microirrigation (15.6%); pumping plant (11.8%); and water well (8.2%). All other irrigation practices accounted for just over 13.5% of the total financial assistance from FY 2014 to FY2023. California (15.52%) and Texas (12.69%) were the top two states for irrigation practice EQIP financial assistance, followed by Colorado (8.09%), Arkansas (7.78%), Utah (5.9%), and Mississippi (5.06%).

- (1) Sprinkler Systems (442) and Irrigation Water Management (449)

NRCS defines sprinkler systems (practice code 442) as a “distribution system that applies water by means of nozzles operated under pressure” (NRCS, Conservation Practice Standard, “Sprinkler System” and “Sprinkler System (Ac.) (442)”). It is commonly applied with irrigation water management (449), irrigation pipelines (430), and pumping plant (533) practices, among others. Irrigation Water Management (practice code 449), for example, is designed to determine and control “the volume, frequence, and application rate of irrigation water” including to “[a]pply water on irrigated lands, efficiently and uniformly” and “[i]mprove water use efficiency” (NRCS, Conservation Practice Standard, “Irrigation Water Management” and “Irrigation Water Management (Ac.)(449)”). Such plans are based on the timing for delivering irrigation water, as well as the amount and rate; the plans are intended to meet crop demands for water, not conservation of water. In fact, the practice standards notably do not address water conservation or reduced consumption.

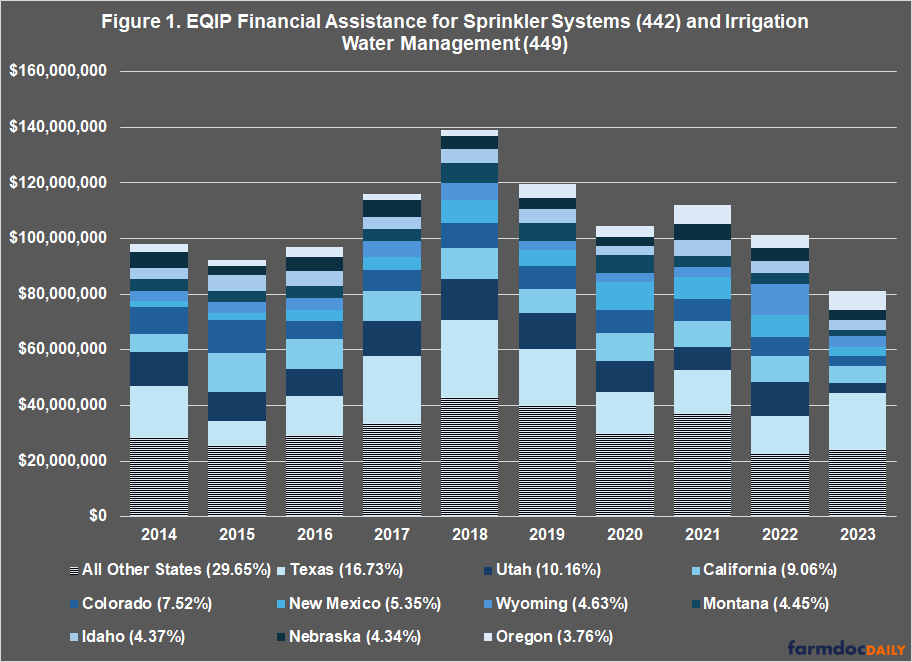

NRCS reports a total of just over $1 billion spent on these practices from FY2014 to FY2023. Figure 1 illustrates funding for the top ten states and all other states for each of the last 10 fiscal years. Texas (16.73%) receives the most funding, followed by Utah (10.16%), California (9.06%), and Colorado (7.52%).

- (2) Irrigation system-microirrigation (441)

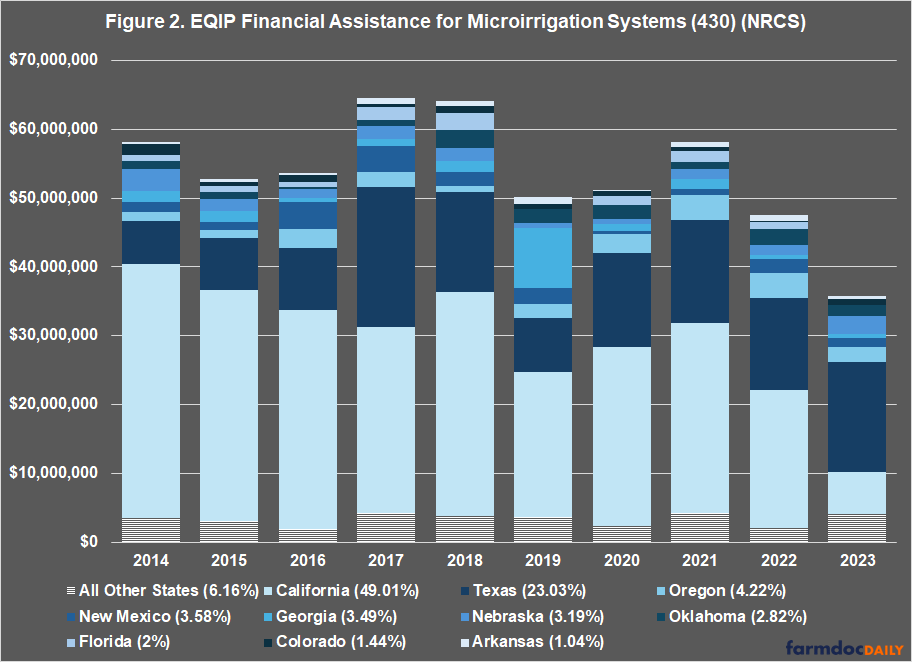

NRCS reports over $535 million obligated for microirrigation practices from FY2014 to FY2023. Microirrigation systems are defined as “frequent application of small quantities of water on or below the soil surface as drops, tiny streams, or miniature spray through emittters or applicators placed along a water delivery line” (NRCS, Conservation Practice Standard, “Irrigation System, Microirrigation” and “Irrigation System, Microirrigation (Ac.)(441)”). By comparison, Sprinkler System (442) is to be used for “systems that wet the entire field and typically have design discharge rates of 60 gallons per hour or greater” (Id.). Microirrigation practices also require development of an irrigation water management plan under practice code 449, but otherwise does not include any requirements for reductions in water consumption or other forms of water conservation. Research has found that this practice can improve water use efficiency and reduce water demand or consumption (see e.g., Anyango et al., 2024).

Figure 2 illustrates the financial assistance for microirrigation practices for the top ten states and all others from FY2014 to 2023. California (49%) and Texas (23%) receive almost three-quarters of the funding for this practice.

- (3) Irrigation Pipelines (430), Pumping Plant (533), and Water Well (642)

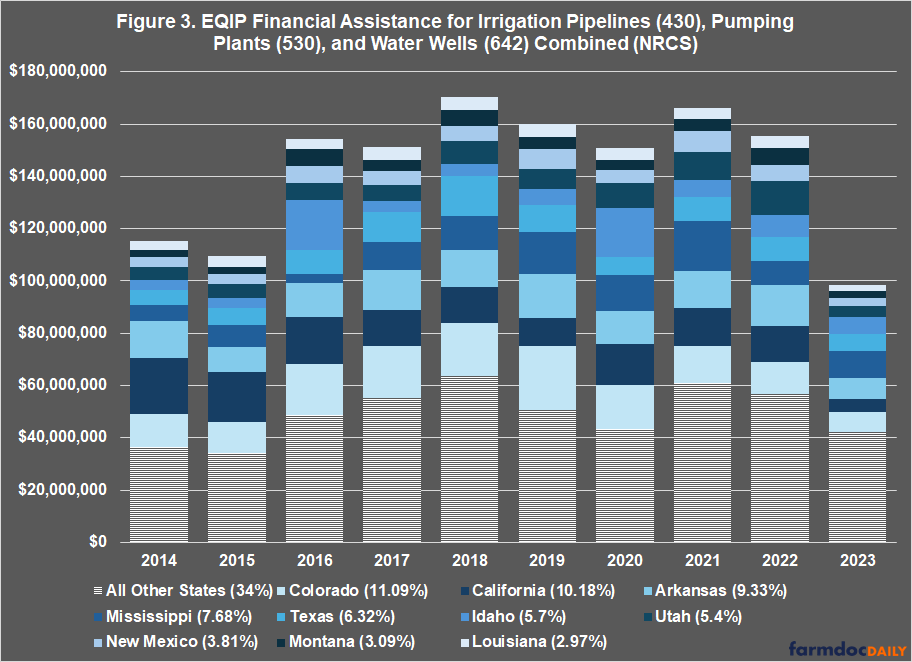

Combined, these three practices have received over $1.4 billion in financial assistance from EQIP in the ten fiscal years FY2014 to FY2023. Irrigation pipelines (430) received $769 million, pumping plants (533) received $392 million, and water wells (642) received $270.5 million during those fiscal years. NRCS defines pipelines as those “appurtenances installed to convey water for storage or application as part of an irrigation system” but not for livestock water or waste transfer (NRCS, Conservation Practice Standard, “Irrigation Pipeline” and “Irrigation Pipeline (Ft.)(430)”). A pumping plant is a “facility that delivers water or wastewater at a designed pressure and flow rate” to provide “efficient use of water on irrigated land” but also to remove excess water and transfer livestock waste (NRCS, Conservation Practice Standard, “Pumping Plant” and “Pumping Plant (No.) (533)”). Finally, a water well practice is a “hole drilled, dug, driven, bored, jetted, or otherwise constructed into an aquifer for agricultural water supply” and can be used for livestock, wildlife and crop irrigation needs (NRCS, Conservation Practice Standard, “Water Well” and “Water Well (No.) (642)”). Notably, each of these practices includes some consideration for water quantity downstream or in aquifers, as well as impacts on other water users or uses. Other than these considerations, the practices do not include any explicit requirements that they be used for water conservation or reductions in the consumption of water.

Figure 3 illustrates the combined financial assistance for these three practices for the top ten states and all other states from FY2014 to FY2023. Colorado (11.09%) and California (10.18%) have received the most, followed by Arkansas (9.33%), Mississippi (7.68%) and Texas (6.32%).

For an interactive visualization of conservation data, the Policy Design Lab website has been updated and allows users to see maps of allocations by State and practice (Policy Design Lab: EQIP). Users can select individual practices, such as the irrigation practices discussed herein, or combinations of practices and the map will adjust with the selection. It also provides for downloading the data. The website currently displays date only for FY2018 to FY2022 but future developments will bring it up to the most recent reported data and extend back to FY2014.

Concluding Thoughts

The effectiveness of conservation policies, as well as for the funding spent, for protecting or conserving water resources depends on the complex interaction of the federal policy with state water laws. Limited conservation dollars risk having “the perverse consequence of actually increasing rather than decreasing groundwater extraction” (Sears et al., 2018). In recognition of this challenge, NRCS recently produced a “Western Water and Working Lands Framework for Conservation Action” (NRCS, January 2024). Among the challenges reviewed are those for sustaining agricultural productivity under dry climates, protecting groundwater in aquifers, and protecting surface water supplies in the driest areas. NRCS emphasizes strategies to reduce withdrawals from groundwater aquifers and surface water sources, modernize water storage and delivery infrastructure, as well as improve efficient uses of irrigation systems. The framework also seeks to better align aquifer use with recharge rates, as well as assist with aquifer recharge projects. While the effort recognizes the importance and impacts of state water laws, there are no strategies for, or solutions to, this fundamental quandary. Whether conservation policies can be designed to address it remains an open question and the subject of future articles in this series.

References

Anyango, Geophry Wasonga, Gourav Dhar Bhowmick, and Niharika Sahoo Bhattacharya. “A critical review of irrigation water quality index and water quality management practices in micro-irrigation for efficient policy making.” Desalination and Water Treatment (2024): 100304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dwt.2024.100304.

Coppess, J. and J. Glenn. “Conservation Quandaries, Part 2: Water Law.” farmdoc daily (15):38, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, February 27, 2025. https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2025/02/conservation-quandaries-part-2-water-law.html.

Frisvold, George B. Technology-Based Water Conservation Programs: All Buck, No Bang. American Enterprise Institute, 2024. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep58533.

Grafton, R. Quentin, John Williams, Chris J. Perry, Francois Molle, Claudia Ringler, Pasquale Steduto, Brad Udall et al. “The paradox of irrigation efficiency.” Science 361, no. 6404 (2018): 748-750. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat9314.

Khanna, Madhu, and David Zilberman. “Inducing water conservation in agriculture: Institutional and behavioral drivers.” Choices 32, no. 4 (2017): 1-3. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26487412

Lankford, Bruce A. “Resolving the paradoxes of irrigation efficiency: Irrigated systems accounting analyses depletion-based water conservation for reallocation.” Agricultural Water Management 287 (2023): 108437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2023.108437.

Li, Haoyang, and Jinhua Zhao. “Rebound effects of new irrigation technologies: The role of water rights.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 100, no. 3 (2018): 786-808. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aay001.

Pfeiffer, Lisa, and C-Y. Cynthia Lin. “Does efficient irrigation technology lead to reduced groundwater extraction? Empirical evidence.” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 67, no. 2 (2014): 189-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2013.12.002.

Pfeiffer, Lisa, and C-Y. Cynthia Lin. “Groundwater pumping and spatial externalities in agriculture.” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 64, no. 1 (2012): 16-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2012.03.003.

Schaible, Glenn, and Marcel Aillery. “Water conservation in irrigated agriculture: Trends and challenges in the face of emerging demands.” USDA-ERS Economic Information Bulletin 99 (2012). https://www.ers.usda.gov/sites/default/files/_laserfiche/publications/44696/30956_eib99.pdf?v=97889.

Sears, Louis, Joseph Caparelli, Clouse Lee, Devon Pan, Gillian Strandberg, Linh Vuu, and C-Y. Cynthia Lin Lawell. “Jevons’ paradox and efficient irrigation technology.” Sustainability 10, no. 5 (2018): 1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051590.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. Natural Resources Conservation Service. “Western Water and Working Lands Framework for Conservation Action.” January 2024. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2024-07/Western-Water-and-Working-Lands-Framework-for-Conservation-Action_0.pdf.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. “Irrigated Agriculture: Technologies, Practices, and Implications for Water Scarcity.” GAO-20-128SP. November 12, 2019. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-128sp.

Wallander, Steven. “USDA water conservation efforts reflect regional differences.” Choices 32, no. 4 (2017): 1-7. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26487414.

Wallander, Steven, and Michael S. Hand. “Measuring the impact of the environmental quality incentives program (EQIP) on irrigation efficiency and water conservation.” (2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.103269.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.