Are Gasoline Prices Still High Relative to Crude Oil Prices?

The downdraft in crude oil prices picked up steam in the last few months, with Brent prices dropping into the low $30s, the lowest level since early 2004 (Figure 1). Throughout the steep decline in crude oil prices, as one would expect, gasoline prices also dropped. However, gasoline prices at the pump in the U.S. through the summer of 2015 remained surprisingly high relative to crude oil prices (farmdoc daily, August 28, 2015; October 8, 2015). The most likely explanation was that the combination of an improving U.S. economy and sharply lower crude oil prices spurred gasoline demand and pushed the production capacity of the U.S. refining industry to the limit. The purpose of today’s article is to examine whether the pressure on gasoline prices has abated in the last six months.

Analysis

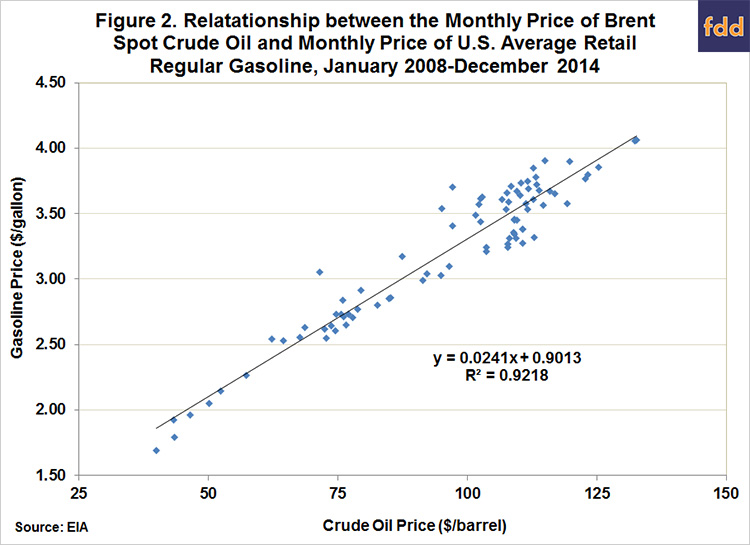

We begin by reviewing the relationship between crude oil prices and retail (pump) gasoline prices in the U.S first presented in the farmdoc daily article of August 28, 2015. Figure 2 shows a scatter plot of monthly spot prices for Brent crude oil and monthly U.S. average prices for retail regular gasoline (conventional and reformulated) over January 2008-December 2014. Brent crude oil prices are considered because Brent prices have predicted U.S. gasoline prices better in recent years, as pointed out by Jim Hamilton (May 16, 2012, June 24, 2012; June 21, 2014) and others. The Brent crude oil price series is collected by the EIA and found here. The February 2016 Brent price is estimated based on the average of daily prices through February 16. Regular gasoline prices also are collected by the EIA and can be found here. The February 2016 gasoline price is estimated based on the average of the first four weekly prices in February. With an R2 of 0.92, the fit of the relationship is quite good. The coefficients also have a sensible interpretation. Since a barrel of crude oil contains 42 gallons, a logical slope is simply 1/42 or 0.024. The slope estimate in Figure 1, at 0.0241 is remarkably close to this predicted value. The intercept, 0.9013, estimates the national average of: i) state and federal gasoline taxes; ii) refinery margins, and iii) transportation other markup costs.

Figure 3 presents predicted and actual U.S. average regular gasoline prices over January 2008 through February 2016. The predicted values were computed using the regression coefficients presented in Figure 1. For example, the January 2011 Brent crude price was $96.52 per barrel. The regression relationship predicts a U.S. average gasoline price of $3.23 per gallon (0.9013 + 0.024 X 96.52), which compares to the actual monthly average gasoline price of $3.10 per gallon in January 2011. Since the regression model was estimated over January 2008 – December 2014, the predicted gasoline prices in 2015 and 2016 are truly “out-of-sample.” As noted in this earlier farmdoc daily articles (August 28, 2015; October 8, 2015), the regression model substantially underestimated gasoline prices through August 2015. For example, the model predicted an August 2015 average gasoline price of $2.02 when the actual price turned out to be $2.64, a whopping $0.62 difference. But, since that time the gap between the model prediction and actual gasoline prices has narrowed substantially. The gap was in the range of $0.20 to $0.30 from September 2015 through January 2016 and was estimated to drop to $0.10 in February 2016. This indicates that the pressure on gasoline prices relative to crude oil has lessened substantially in the last six months.

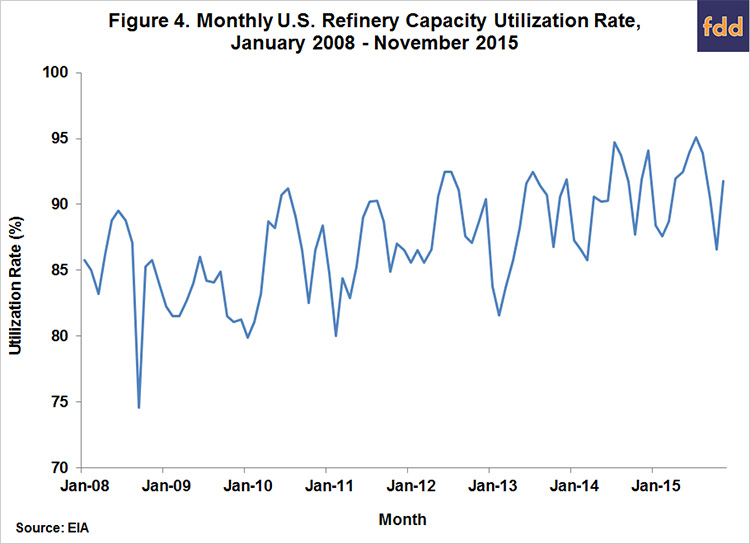

If the relative strength in gasoline prices through the summer of 2015 could be traced to a surge in gasoline demand that strained the production capacity of the U.S. refining industry, then we should see less of a “stretch” in refining capacity during the last six months that parallels the easing of gasoline prices relative to crude oil. Figure 4 shows the capacity utilization rate for the U.S. crude oil refining industry over January 2008 through November 2015 (latest available data) as computed by the EIA. Given the seasonal peak in driving during the summer, it is no surprise that capacity utilization of refineries also has the same seasonal tendency. There has been a trend towards higher capacity utilization over time with the recovery from the Great Recession of 2008-09. A notable jump in utilization rates started in May 2015 and reached a new peak for this period of 95.1 percent in July 2015. There was indeed a sharp drop in utilization rates last fall, reaching a low of 86.6 percent in October. Some recovery was evident in November, but, overall, this data suggests an easing of refinery capacity utilization in the last six months, consistent with the decline in the price of gasoline relative to crude oil.

An interesting question, then, is what happens moving forward, especially in next summer’s peak driving season. Some perspective is provided by Figure 5, which presents a widely-followed indicator of transportation fuel demand in the U.S. Specifically, the 12-month moving total of U.S. miles travelled on all roads over January 1991 through December 2015. This data is compiled monthly by the Department of Transportation. The use of a moving total smooths out the noise in monthly data and helps to better identify underlying trends on an annual basis. The chart shows a very steady gain in miles driven between 1991 and 2007, with a peak of a bit over 3,000 billion miles (12-month total) in late 2007 and early 2008. The trend-line for this period has a slope of 4.8, indicating a trend increase of 4.8 billion miles per month. The combined impact of high crude oil prices and the Great Recession pushed miles driven down fairly sharply in the second half of 2008 and 2009. This was followed by a plateau at around 2,950 billion miles through 2012. Miles driven slowly began to recover in 2013 and 2014, and then began rising sharply in 2015, coinciding with the large drop in the price of gasoline. At the end of 2015, miles driven stood at 3,147 billion miles, or 7 percent above the low during the post-2008 period. So, U.S. drivers have clearly responded to lower gasoline prices by increasing miles driven, which, abstracting from any gains in fuel efficiency, implies a higher quantity demanded for gasoline. Given the additional decline in gasoline prices in recent weeks and the anticipated global glut of crude oil through at least 2016, there is every reason to believe that the sharp uptick in miles driven will continue. This means that refinery capacity could be pushed to the limit by the upcoming summer driving season, which once again would put upward pressure on pump gasoline prices relative to crude oil.

Finally, it is interesting to consider the possibility that miles driven will eventually recover back to the pre-2008 trend. While the current gap between the pre-2008 trend and miles driven certainly is large, at the recent growth rate of 3.5 percent year-over-year, miles driven could recover back to the old trend in a little under four years. This may seem wildly optimistic given the long period of relatively flat miles driven and the possibility that U.S. driving habits have been permanently reduced due to an aging population and even social media. But, the sharp recovery in miles driven in the last year indicates the powerful effect of lower gasoline prices on U.S. driving habits remains intact. So long as gasoline prices stay low it is reasonable to expect a continued and substantial recovery in total U.S. miles driven.

Implications

U.S. gasoline prices at the pump through the summer of 2015 were surprisingly high relative to crude oil prices, in all likelihood driven by an improving U.S. economy and sharply lower crude oil prices, which, in combination, spurred gasoline demand and pushed the production capacity of the U.S. refining industry to the limit. Since last summer the gap between gasoline prices predicted by the historical relationship to crude oil prices and actual gasoline prices has narrowed substantially. The gap was in the range of $0.20 to $0.30 per gallon from September 2015 through January 2016 and dropped to an estimated $0.10 in February 2016. This indicates that the pressure on gasoline prices relative to crude oil has indeed lessened substantially in the last six months. The lessening pressure on gasoline prices can be traced to an easing of refinery capacity utilization rates in the last six months. However, this situation may not last. The sharp recovery in U.S. miles driven in the last year indicates the powerful effect of lower gasoline prices on U.S. driving habits remains intact and the upcoming peak summer driving season could once again push U.S. refining capacity to the limit.

References

Hamilton, J. "Gasoline price calculator." Econbrowser, June 21, 2014. http://econbrowser.com/archives/2014/06/gasoline-price-calculator

Hamilton, J. "Gasoline prices coming down." Econbrowser, June 24, 2012. http://econbrowser.com/archives/2012/06/gasoline_prices_7

Hamilton, J. "Oil and gasoline prices." Econbrowser, May 16, 2012. http://econbrowser.com/archives/2012/05/oil_and_gasolin

Irwin, S. "Where Are Gasoline Prices Headed?" farmdoc daily (5):158, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 28, 2015.

Irwin, S. "Why are Gasoline and Diesel Prices So High? (Relative to Crude Oil Prices)." farmdoc daily (5):186, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, October 8, 2015.

U.S. Department of Transportation. Traffic Volume Trends. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/travel_monitoring/tvt.cfm

U.S. Energy Information Administration. "Petroleum & Other Liquids: Spot Prices." Released August 19, 2015, accessed February 24, 2016. http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_pri_spt_s1_d.htm

U.S. Energy Information Administration. "Weekly Retail Gasoline and Diesel Prices." Released August 17, 2015, accessed February 24, 2016. http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_pri_gnd_dcus_nus_w.htm

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.