Yield Updating and the Current Versions of the Farm Bill

General updating of program yields is not allowed in current House or Senate versions of the 2018 Farm Bill. However, the House version does allow for program yield updating in drought-designated areas centering in the southern Great Plains and in the Southeast. There is little empirical evidence that suggests updating is needed more in these drought-designated areas than in non-designated counties. In fact, the drought-designated regions do not include the areas impacted by the major 2012 drought.

Program Yields for a Farm

Each Farm Service Agency (FSA) farm has a set of yields used to calculate payments for Price Loss Coverage (PLC). One program yield exists for each crop with base acres on an FSA farm. When a crop’s market year average price is below the statutory set reference price, there will be PLC payments. FSA farms with higher program yields will receive higher payments. Hence, the ability to update yields to higher levels is desirable.

Program yields have a long history and cannot be changed unless legislation allows for updating. The 2014 Farm Bill allowed for updating (see farmdoc daily, April 3, 2014). Landowners of FSA farms could choose to keep the existing program yields or update those yields to 90% of average farm yields for the years from 2008 to 2012.

Program Yield Updating Under Proposed 2018 Farm Bill

Neither of the current 2018 version of the farm bills from the House or Senate allows yield updating across the nation. However, the House version does allow for updating under a specific situation. In particular, updating would be allowed on FSA farms located in counties where the U.S. Drought Monitor rated that county as having an exceptional drought for 20 or more consecutive weeks during the period beginning on January 1, 2008, and ending on December 31, 2012, which is the same period designated by the 2014 Farm Bill for updated yields.

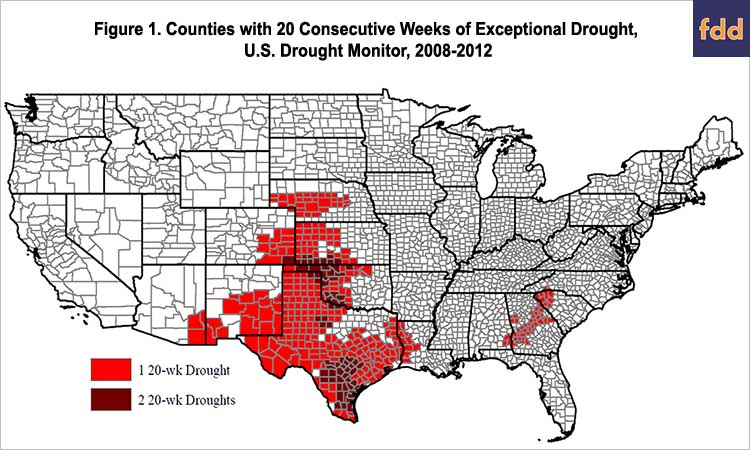

As one would expect, there is a geographical pattern to the counties where the House update criteria would be met, with two general areas where updating will be allowed (see Figure 1). The first is in the southern Great Plains including many counties in Texas, western Louisiana, western Oklahoma, western Kansas, western Nebraska, eastern Colorado, and some counties in New Mexico and Arizona. The second includes a stretch of counties in middle Georgia extending down into Alabama and up into South and North Carolina.

Issues with the Drought Yield Updating Criteria

Presumably, the House included the yield updating provision because farmers and landowners were disadvantaged in the drought-designated areas. Because the 2014 Farm Bill update used a simple average of all years with yields, the increase in PLC yields may be less in the drought-designated counties than in non-designated counties.

There are at least two issues associated with a drought-dependent yield update. The first is related to the complexity of yield determination. While yields are highly related to having adequate moisture, drought indicators are not necessarily indicators of yield reductions. For example, the timing of a drought matters. A 20-week drought may not have much impact on yields if it occurs outside the growing season.

The second is that yield can be negatively impacted by a drought that is less than 20 weeks in length. The 2012 drought was a major event having significant impact on corn yields, yet it does not show up in Figure 1. While not 20-weeks in length, the 2012 drought occurred during the critical corn-pollination period. The 2012 drought was centered in an area from eastern Kansas through Kentucky, including large impacts in south Illinois and Indiana. Many counties had yields that were over 35% below trend yields (farmdoc daily, February 20, 2013).

Whether or not individuals were more significantly impacted in the area identified in the House Farm Bill is an empirical issue. In the following sections, loss ratios and yields are compared within and outside the drought-designated areas.

Loss Ratios

Figure 2 shows loss ratios from the Federal crop insurance program for the years from 2008 through 2012, the period allowed for program yield updating under the 2014 Farm Bill and the drought-designation period under the House version of the next Farm Bill. Yields are a critical component influencing crop insurance payments, especially during this period of generally increasing prices. Higher loss ratios indicate more insurable losses.

Many counties in drought-designated areas had high loss ratios, notably Texas, western New Mexico, and parts of Oklahoma. However, there are areas outside the drought-designated areas with high loss ratios are well. In particular, an area beginning in eastern Kansas, Missouri, southern Iowa, southern Illinois, southern Indiana, Kentucky, and parts of Tennessee had high loss ratios. High loss ratios in this particular area reflect the 2012 drought.

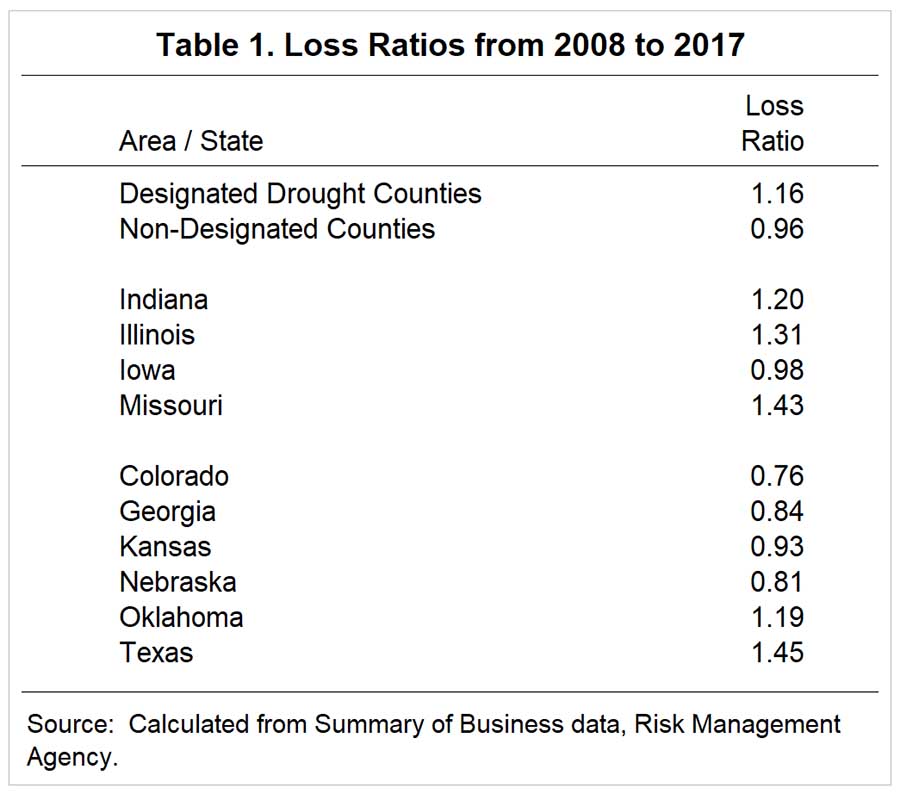

Overall loss ratios in drought-designated counties averaged 1.16, slightly higher than the .96 loss ratio from the non-designated counties (see Table 1). Among non-designated counties there were areas well above the average for the drought-designated counties. Missouri had a 1.43 loss ratio, Illinois a 1.31 loss ratio, and Indiana a 1.30 loss ratio (see Table 1).

Yields

Yields were compared for the 2008 to 2012 period to yields for the five years immediately preceding the yield updating/drought-designation period – the years from 2003 to 2007. This comparison was done by calculating county yield ratios using National Agricultural Statistical Service (NASS) yields. For all counties with complete data for all 10 years, the 2008 to 2012 average was calculated and divided by the average from 2003 to 2007. Lower ratios would suggest that yields were more adversely impacted in the 2008-2012 period.

For corn, the 2008-2012 to 2003-2007 yield ratios averaged .94 for drought-designated counties and 1.00 for non-designated counties (see Table 2). However, yield ratios were .93 for Indiana, .93 for Illinois, .95 for Iowa, and .95 for Missouri.

For soybeans, yield ratios in drought-designated counties were 1.00 compared to 1.05 for non-drought designated counties. Again, there was diversity in yield ratios across the counties. Indiana had yield ratios below the average for the drought-designated counties.

Wheat yield ratios were near one another. Drought-designated counties had an average yield ratio of 1.04 compared to 1.07 for non-designated counties.

For cotton, drought-designated counties had a .98 yield ratio, below the 1.11 for non-desingated counties. There was a wide diversity in yields. Georgia had a yield ratio of 1.15 compared to Texas which had a .96 yield ratio (see Table 2). On the other hand, Arkansas had yield ratios that averaged .96, below the .98 average of the drought-designated counties. Arkansas does not have any counties that would be classified as having a drought.

Summary and Commentary

The House version of the 2014 Farm Bill includes a provision that allows the updating of PLC yields for FSA farms in counties that were classified as having an exceptional drought for 20 consecutive weeks sometime between January 2008 and December 2012. The empirical analyses presented here question whether farmers and landowners in these drought-designated counties were materially more affected by drought than farmers and land owners in other areas. In particular, the definition proposed by the House Farm Bill does not capture the yield reduction resulting from the 2012 drought.

This matter is particularly important as the impacts of these provisions can have long-ranging impacts. Opportunities for yield updating occur infrequently. History suggests that not updating will not be allowed in every farm bill. Hence, giving one area of the country preferences does not seem prudent.

References

Paulson, N., J. Coppess and T. Kuethe. "2014 Farm Bill: Updating Payment Yields." farmdoc daily (4):60, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 3, 2014.

Schnitkey, G. "Locating the 2012 Drought Using State Corn Yields." farmdoc daily (3):32, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, February 20, 2013.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.