The People Behind the Machines: Precision Agriculture and Farm Service Technician Demand

Note: This article was written by University of Illinois Agricultural and Consumer Economics Ph.D. student Parthu Kalva and edited by Joe Janzen. It is one of several excellent articles written by graduate students in Prof. Janzen’s ACE 527 class in advanced agricultural price analysis this fall.

Precision agriculture is a technological solution to rising labor costs in farming. Once installed, digital systems and automated machinery can operate with lower, more predictable marginal costs than human labor, improving both profitability and planning certainty. Yet the notion that technology simply replaces workers overlooks an important reality: rather than simply eliminating labor, precision agriculture modifies the demand for agricultural labor. As automation and digital systems associated with precision agriculture spread, labor demand shifts from manual to technical and analytical work managing and maintaining sensors, robots, and data platforms. This includes both on-farm operators and off-farm specialists who maintain and service the systems. Among these, farm service technicians have emerged as a critical new occupation, installing, calibrating, and maintaining the digital systems embedded within modern farm machinery (GAO 2024).

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) estimates that approximately 36,830 ‘Farm Equipment Mechanics and Service Technicians’ were employed in the US in 2023 (BLS, 2024), but industry sources report a shortage of qualified technicians (e.g. Castillo, 2025). Possible consequences of a shortage are longer wait times for maintenance, which, during planting or harvest, can translate into significant losses for farmers. Scarcity may also drive up technician wages, increasing the cost of dealership service contracts and raising the overall expense of adopting and maintaining advanced technology.

To assess the potential skilled labor shortage related to new technologies in production agriculture, this article examines precision agriculture adoption across US states and how the use of these technologies correlates with employment and wages for farm service technicians. Positive correlation between technology use and both employment and wages suggest precision agriculture is indeed changing the nature of agricultural labor. Higher employment and wages in places where precision agriculture use is high is consistent with some degree of supply response. Workers are acting in response to the need for more service technicians, though perhaps not as quickly as the industry needs or wants.

What Is Precision Agriculture – and Where Is It Happening?

Precision agriculture uses digital technologies to manage variability within fields and improve production efficiency. It combines GPS guidance, sensors, yield monitors, and variable-rate applicators to collect and act on spatial data about soils and crops. These systems allow farmers to apply inputs such as seed, fertilizer, and pesticides more precisely, boosting efficiency while reducing waste and environmental impact. Precision agriculture also addresses broader challenges in agriculture, including rising costs, labor shortages, and climate variability, by increasing control and information at every stage of production.

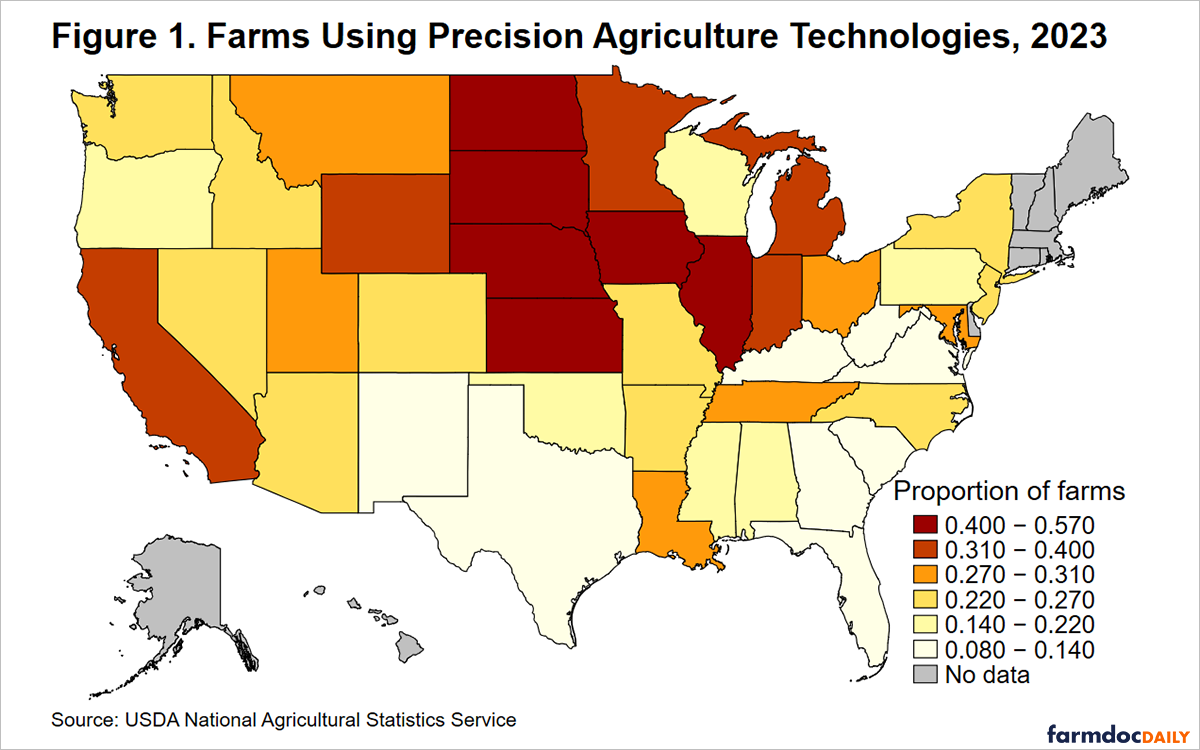

Using data from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) Technology Use report, Figure 1 maps the share of farms using precision agriculture in 2023. Adoption varies sharply across the country, but the leaders cluster in the Midwest. States with large-scale row-crop systems, especially corn and soybean, tend to report the highest use. Many precision tools (auto-guidance, variable-rate application, yield monitors) are fixed-cost add-ons that become relatively cheap per acre as acreage grows. Thus, they plug well into a machinery-intensive production systems where small efficiency gains compound across thousands of acres.

California is an important exception. It produces many labor-intensive specialty crops that may create strong incentives to adopt precision agriculture technologies. High land and labor costs, water scarcity and regulation, and the potential for large payoffs from better irrigation and input targeting can make precision investments attractive even when operations are not dominated by commodity row crops. Many southern and western states show lower adoption intensity, indicating that per-acre gains from precision tools are not large enough to justify upfront costs in these locations.

The Technicians Behind the Technology

Farmers can access precision technologies through several channels, but equipment dealerships—often affiliated with original equipment manufacturers such as John Deere, Case New Holland, and Agco—remain the primary providers. These dealerships supply machinery equipped with precision systems and deliver essential services including installation, calibration, operator training, software updates, and maintenance. Their role increasingly depends on a specialized workforce of farm service technicians. Technicians play a critical role in keeping modern farm equipment and digital systems operational. They install sensors, calibrate controllers, troubleshoot communication networks, update software, and ensure that increasingly complex machinery runs reliably throughout planting and harvest seasons.

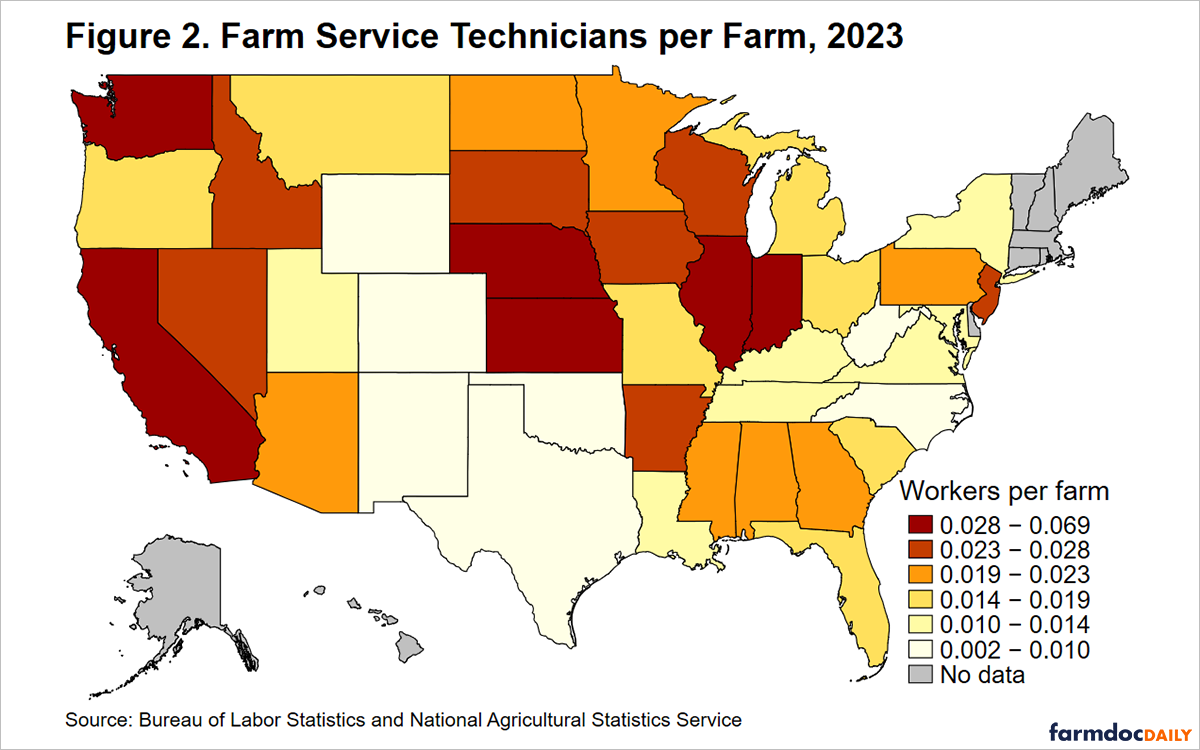

To assess the current landscape of technician availability, this analysis uses 2024 BLS Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) on farm equipment mechanics and service technicians (SOC 49-3041), which OEWS defines as workers who “diagnose, adjust, repair, or overhaul farm machinery and vehicles” (e.g., tractors, harvesters, dairy equipment, irrigation systems) (BLS, 2024). In addition, these jobs mostly reflect off-farm/supply chain roles, where dealership-related employers alone account for two-thirds of the jobs. These data are combined with NASS estimates of the number of farms to compute technician density (measured in workers per farm) across states (USDA NASS, 2025). Normalizing by the number of farms is important because it accounts for simple differences in the relative size of the farm sector across states that might lead to positive correlation between technology use and labor market outcomes.

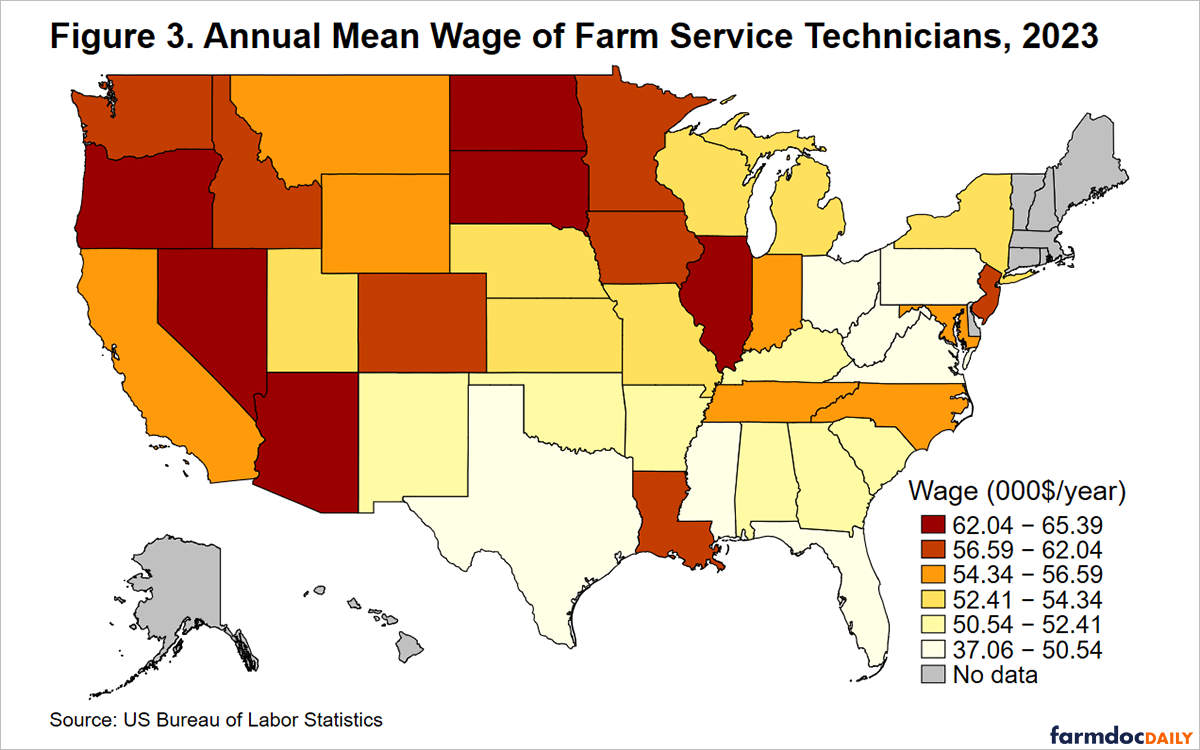

Figures 2 and 3 describe labor capacity, farm service technicians employed per farm, and the price of that capacity, technician wages, respectively. Figure 2 divides US states into quintiles by technician density. Where these workers are most prevalent, there are roughly 3-7 technicians per 100 farms. These farms are generally in the Midwest and West, particularly Corn Belt states, California, and Washington. Figure 3 shows large variation in wages, roughly from the mid-$30,000s to around $60,000 per year. The highest-wage states are not always the same states with the highest technicians-per-farm. Thus, wages seem to reflect not only farm technology demand, but also local labor market conditions (cost of living and competition from other industries) including potential labor scarcity. It is possible that states with tighter technician supply may clear the market through higher pay even if service capacity remains thin.

Precision Agriculture Adoption and Technician Scarcity

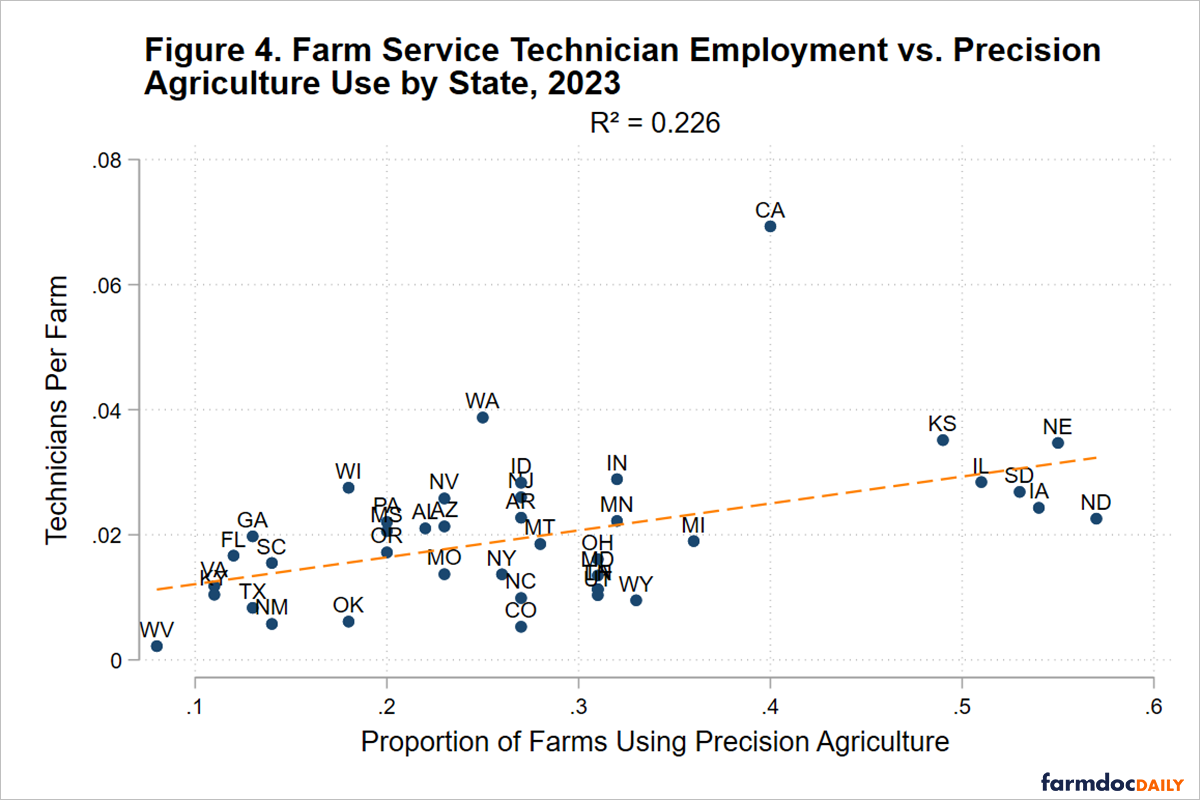

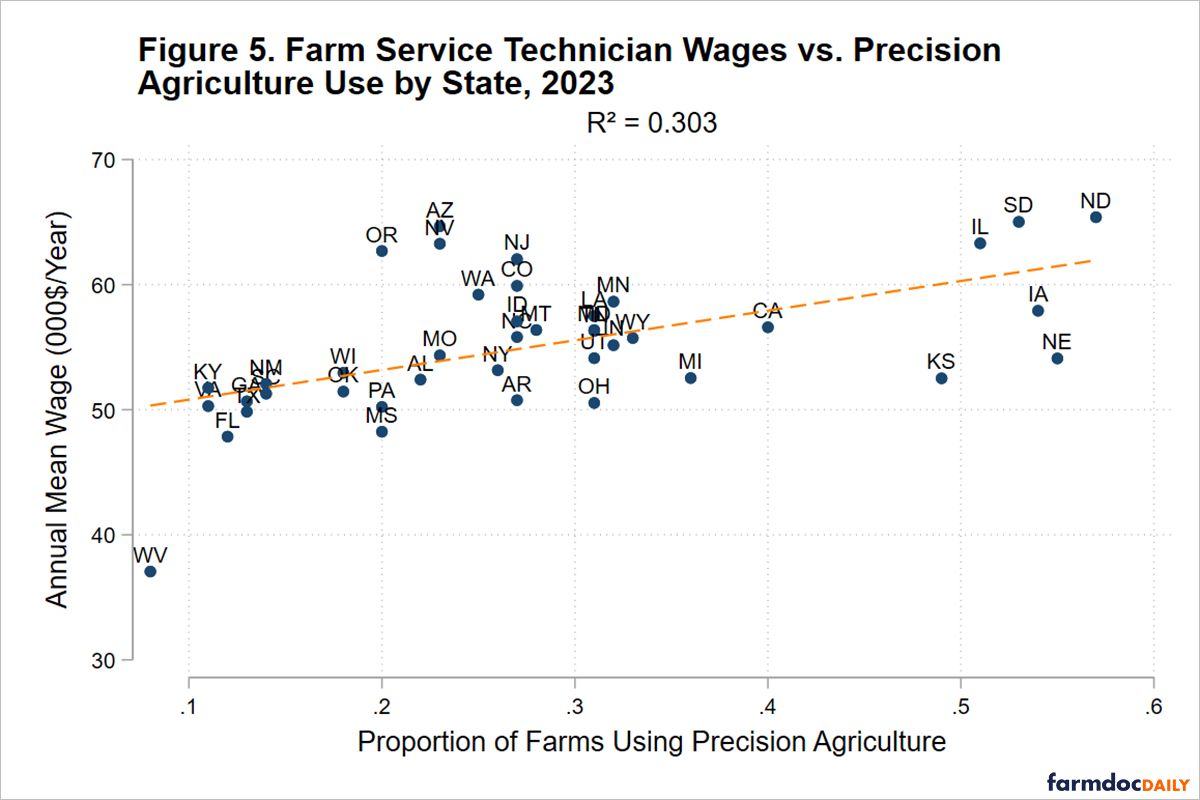

To assess whether precision agriculture technology adoption is changing the nature of agricultural labor demand, adoption rates are correlated with employment and wages for farm service technicians across states. These correlations are visualized in Figures 4 and 5. The results suggest that there is small, positive correlation between state-level precision agriculture adoption and both farm service technician wages and technician employment. This result is consistent with the idea that precision agriculture adoption shifts the demand for technician labor and results in supply response: more technicians are employed per farm and they are employed at higher wages.

While Figures 4 and 5 show states with higher precision agriculture adoption tend to have more agricultural technicians relative to the number of farms and higher wages, the correlation is relatively weak. The R-squared statistics suggest precision ag adoption alone explains only about a quarter of the observed cross-state variation in employment and wages. This analysis cannot assess whether the imperfect nature of the correlation is the result of constrained labor supply (what might be referred to as a labor shortage). It also cannot tell whether such labor constraints are temporary and short-run or persistent, long-run issues. Other unobserved supply and demand factors such as public and industry support for workforce development initiated alongside the adoption of precision agriculture technology, broader labor market conditions such as cost of living and competition from adjacent sectors, and others may also explain why employment and wages vary across states.

The wage figure (average technician wage vs. precision ag use) shows a positive relationship between adoption and pay. Despite some states deviating from the trend, the figure suggests that higher precision adoption is associated with higher technician wages on average. This indicates that technician pay may reflect both technology-driven demand and broader labor-market conditions (cost of living and competition from adjacent sectors), rather than precision adoption alone. Taken together, the two charts imply that precision adoption is moderately related to technician employment capacity and higher wages; however, local workforce pipelines and market structure likely play an important independent role.

Conclusion

Using the NASS and OEWS data, we find that higher precision agriculture use is associated with greater technician employment per farm and higher wages at the state level. This is consistent with a labor supply response to shifting demand caused by the development of new technologies. Precision agriculture is changing the nature of agricultural labor demand. However, the relationships are far from one-to-one. The imperfect nature of these relationships between precision agriculture adoption and technician employment and wages implies that labor supply may be constrained; a farm service technician shortage is real, at least at wage rates near current levels. Efforts to develop a technician and service ecosystem may be needed to sustain existing precision agriculture use and enable the adoption of any new precision agriculture technologies. Remaining cross-state variation indicates that wages and staffing are also shaped by broader labor-market conditions rather than precision adoption alone.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2024. Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) https://www.bls.gov/oes/2023/may/oes493041.htm

Castillo, Andy. 2025. “Search for ag technicians goes outside of farming” Farm Futures https://www.farmprogress.com/farming-equipment/search-for-ag-technicians-goes-outside-of-farming

Government Accountability Office. 2024. Precision Agriculture: Benefits and Challenges for Technology Adoption and Use. GAO Report GAO-24-105962 https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-105962

National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2025. Technology Use (Farm computer usage and ownership). https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Todays_Reports/reports/fmpc0825.pdf

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.