The Reconciliation Farm Bill: Top Five Most Problematic Changes to Farm Policy, #2

The number two position in the top five most problematic changes to farm policy belongs to the third and final entry for crop insurance (farmdoc daily, August 14, 2025 (#4); July 31, 2025 (#5)). That fact alone raises concerns and the most concerning change to crop insurance in the Reconciliation Farm Bill are the increased coverage levels and premium subsidies for the Supplemental Coverage Option (SCO) crop insurance policies. CBO projected an additional $1.4 billion in spending for these changes (CBO, July 21, 2025). Those additional projected costs, like all increases in farm policy assistance, were paid for by reducing food assistance in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). At a monthly average benefit per person, that is the equivalent of helping 7.6 million people purchase food in a month.

Background

The Supplemental Coverage Option (SCO), federally subsidized and reinsured supplemental crop insurance, was created by Congress in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79, Section 11003). Farmers could purchase policies that provided area-wide (e.g., county) coverage from 86% of the insurable yield or revenue down to the underlying buy-up policy that the farmer purchased. Policy premiums were subsidized at 65% of the total cost of the policy premium. The House version of SCO in the 2014 reauthorization effort designed it to begin coverage at 90% of the area (county) loss but the conference committee settled on 86% coverage, or a 14% deductible range (113 H.R. 2642eh).

Importantly, SCO created a much closer linkage to the farm program subsidy programs, ARC and PLC. SCO was designed, especially, as a counter to the ARC-CO program (calculated using 86% of the five-year Olympic moving average county yields). If a farmer enrolled the base acres of a crop in ARC-CO, they were not able to purchase SCO regardless of the decoupled design of the former but not the latter. Because it was included in the crop insurance title, SCO was permanently authorized and not at risk of expiration like ARC and PLC. Considering that the 2014 Farm Bill eliminated direct payments under budget pressures, building a permanently authorized alternative in crop insurance as a backstop to future pressures against farm subsidy programs may have been an unstated part of the reasoning. Either way, SCO blurred the lines between decoupled farm subsidies and subsidized crop insurance—a point that takes on new meaning with the changes in the Reconciliation Farm Bill discussed herein.

Discussion

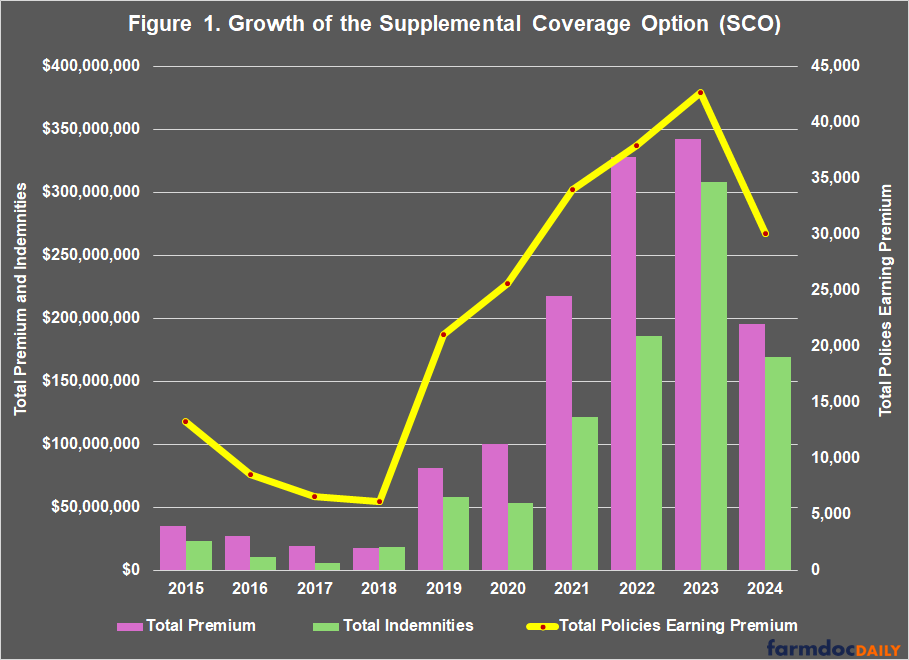

After an initial slow start, SCO has grown in recent years. Figure 1 illustrates the policy’s growth in total premium, total indemnities and total policies earning premium as reported by USDA’s Risk Management Agency (USDA-RMA, Summary of Business). Total policies earning premium topped 20,000 nationwide in 2019, peaked at over 42,000 in 2023 but dropped to just over 30,000 in 2024. The data from these six years will be used throughout the discussion.

Section 10502 of the Reconciliation Farm Bill (P.L. 119-21) revises the authorization for SCO (7 U.S.C. §1508(c)(4)(C)). Specifically, it increases the coverage level to 90% (or a 10% deductible range) down to the underlying buy-up coverage level the farmer purchases. It also increased premium subsidy to 80% of the cost of the premium. Finally, Congress removed the restriction on a farmer’s ability to purchase SCO if base acres are enrolled in ARC-CO.

The only reasonable interpretation of these changes is that Congress wants to encourage further growth of the program and increase the purchase of SCO policies by farmers (or sales by the crop insurance industry). Increasing premium subsidy and coverage to such high levels for an area-wide crop supplemental crop insurance option also raises concerns that Congress is transforming SCO into a direct payment program for high risk areas but disguised as crop insurance (farmdoc daily, June 10, 2025; June 13, 2024). Creating a direct payment program masquerading as crop insurance is problematic, to say the least. It is also rather complicated.

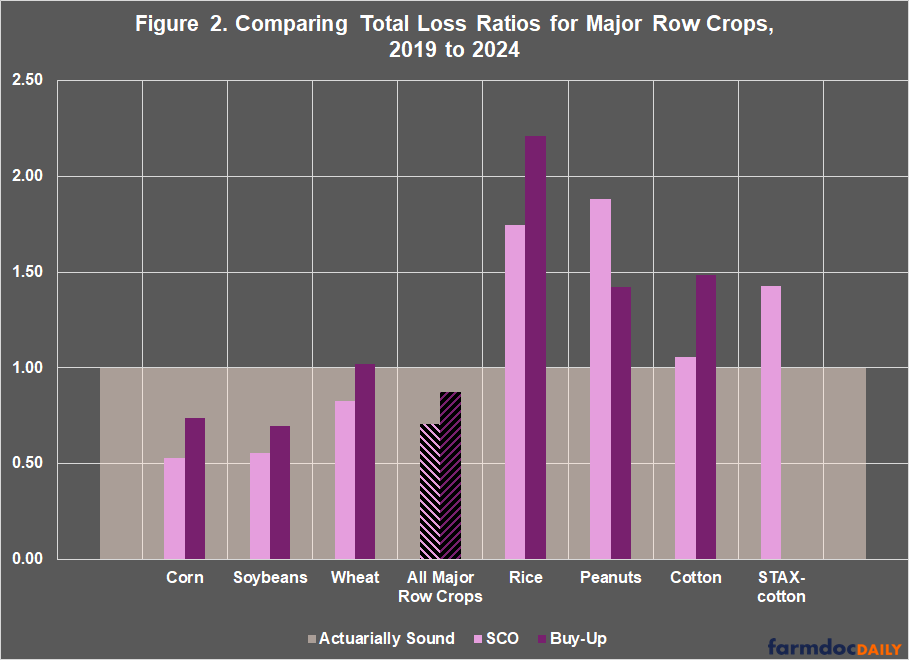

First, consider the actuarial performance of SCO, calculated as the loss ratio (total indemnities divided by total premiums) for corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, rice, and peanuts, as well as a total for all major row crops (including the other feed grains: barley, oats, rye, and sorghum). Figure 2 illustrates the total loss ratio for the years 2019 to 2024 for both SCO and buy-up coverages for each. Figure 2 also includes the additional area-wide crop insurance option available only to cotton farmers, the Stacked Income Protection Plan for Producers of Upland Cotton (STAX). It is included in Figure 2 for additional comparison and because it is relevant, although Congress did not revise the program in the Reconciliation Farm Bill. STAX is also an area-wide (e.g., county) insurance policy with coverage beginning at 90% of the insurable revenue, down to 70% of insurable revenue. Like SCO it was available on top of, or supplemental to, the underlying individual buy-up insurance policy. Congress also created it in the 2014 Farm Bill.

It should be of little surprise by now that the southern crops (cotton, rice, and peanuts) are the ones with loss ratios above 1.0 for SCO in these years, although the loss ratio for wheat buy-up coverage was 1.02 for these years. Rice has the highest loss ratio for buy-up coverage (2.21) and the second highest for SCO (1.75). Peanuts has the highest loss ratio for SCO (1.88) but had a slightly lower loss ratio (1.42) than did cotton (1.48). The SCO loss ratio for cotton was 1.06 but was 1.43 for STAX.

A second measure for crop insurance policies is the benefit ratio, calculated as the total indemnities divided by the total amount farmers paid for crop insurance. This is another measure of crop insurance and is included in the interactive map in Figure 3 along with loss ratios. These measures are the State totals for the last 10 years (2015 to 2024). The higher the benefit ratio, the more the farmer receives from the crop insurance policy relative to what the farmer pays for insurance, the ratio factors in both indemnities and premium subsidy. The benefit ratio should always be higher than the loss ratio due to premium subsidy, but the differences between the two are instructive.

This kind of insurance policy, supplemental and area-based, kicks up many interesting questions. For a farmer, those questions would presumably begin with whether the policy is worth purchasing. That question includes whether it is worth adding SCO on top of an individual policy at the highest levels (80% or 85%) of coverage, or whether it makes sense to buy down the individual policy, trading farm-level coverage for the area or county. Much depends on the whether the farm’s loss experiences or expectations match the county. For example, if the farm experiences losses but the county does not, SCO would seem like a bad option. If, however, the county experiences losses when the farm doesn’t, SCO could be a good option. The benefit ratio is informative for the farmer as a measure of whether different types of policies are worth purchasing. Where the benefit ratio for SCO is less than for standard buy-up policies, for example, farmers might be advised to skip it, or at least be careful about buying down standard coverage to add in SCO.

Concluding Thoughts

With the changes in the Reconciliation Farm Bill, Congress is encouraging farmers to purchase Supplemental Coverage Option crop insurance policies, possibly including trading off high-levels of individual buy-up coverages for SCO. Increasing the coverage levels (or decreasing the deductible) and increasing the premium subsidy for the Supplemental Coverage Option crop insurance policies is likely to prove problematic to the insurance program over time. Experience with the policy in the ten years it has been in existence raises many difficult questions, beginning with the rating of these policies by USDA. If the ratings are incorrect now, increasing premium subsidy and coverage levels will not improve things. This review of SCO adds further to the existing questions about the operational performance of these policies, including whether they are rated properly (farmdoc daily, June 10, 2025; June 13, 2024).

While it is subsidized by the taxpayer, crop insurance works because many farmers pay more into the system than they receive from it—that is the very essence of insurance, as compared to direct subsidy programs which rely only on taxpayer funds. Unfortunately, the changes to SCO in the Reconciliation Farm Bill are the second-most problematic because they add to existing and serious problems with the policy. From the start, SCO raised concerns because it was designed as an alternative to ARC-CO and could be purchased only in conjunction with PLC. Designed this way significantly blurred the lines between direct subsidies and subsidized crop insurance. Increasing premium subsidy and coverage levels magnifies those concerns, pushing SCO insurance over the line into a direct subsidy policy for high-risk areas but disguised as crop insurance.

At the federal policy level (including the cost to the taxpayer), there are important differences between the decoupled subsidy programs and the subsidized insurance policies, beginning with the decoupled design. Crop insurance is necessarily coupled to production and planting decisions. The more SCO operates like a coupled subsidy program, the more it is likely to influence farmers’ planting decisions; because it works that way best in high-risk areas, moreover, the consequences could be substantial. This includes increased costs to the taxpayer but also the myriad consequences of encouraging production in high-risk areas and for high-risk crops. From water consumption to soil erosion and more, important risks are not covered by crop insurance and impact people far from the farm field.

For farmers (or at least those that pay more for insurance than they receive), the issues here are more direct but equally concerning. If SCO becomes a direct subsidy program disguised as crop insurance, it will require more farmers on the other side of the disguise paying into the program with decreasing benefits. It is basic math and common sense: some farmers must pay without expectation of receiving indemnities to cover the costs of those farmers who are using it for direct payments. Farmers purchasing crop insurance with no expectation of an indemnity are effectively making an indirect donation to those who expect the indemnity; or, looked at another way, they are paying a tax on the policies they purchase with no expectation of receiving benefits, which is transferred to farmers in those areas where indemnities are consistent and expected. Combined, these changes in the Reconciliation Farm Bill earning SCO its spot as the second most problematic change to farm policy.

References

Congressional Budget Office. “Estimated Budgetary Effects of Public Law 119-21, to Provide for Reconciliation Pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Relative to CBO’s January 2025 Baseline.” Cost Estimate. July 21, 2025. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61570.

Coppess, J. "The Reconciliation Farm Bill: The Top Five Most Problematic Changes to Farm Policy, #5." farmdoc daily (15):139, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 31, 2025.

Coppess, J. "The Reconciliation Farm Bill: Top Five Most Problematic Changes to Farm Policy, #4." farmdoc daily (15):147, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 14, 2025.

Schnitkey, G., B. Sherrick, C. Zulauf, N. Paulson and J. Coppess. "The House Reconciliation Bill Proposal for SCO: Income Support for High-Risk Farmland." farmdoc daily (15):106, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 10, 2025.

Schnitkey, G., J. Coppess, N. Paulson, C. Zulauf and B. Sherrick. "Cotton STAX and Modified Supplemental Coverage Option: Concerns with Moving Crop Insurance from Risk Management to Income Support." farmdoc daily (14):111, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 13, 2024.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.