Reviewing Farm Bill History: Budgets, Boll Weevils and the 1981 Farm Bill

The second in this series reviewing farm bill history looks for lessons in the 1981 Farm Bill debate (farmdoc daily, February 16, 2017). It took place in the early stages of what became the second great farm economic crisis which consumed much of the 1980s.

Background

Congress had written two bills prior to the 1981 Farm Bill, but the Agricultural and Consumer Protection Act of 1973 was the more consequential. In 1973, Congress substantially revised the farm bill at a time when commodity prices were spiking. First, Congress formally combined food stamps with farm support programs to build a broad coalition of votes that had become necessary to pass the farm bill. Second, Congress created a target price system of farm support, making direct deficiency payments to farmers when average market prices fell below Congressionally-fixed target prices. Target price policy was considered a market-oriented reform after decades of parity-based price supporting loans; an incentive for farmers to expand production in response to export market optimism and high prices.

Farmers responded to the production incentives created by higher prices and the new target price policy, as well as encouragement from the Nixon Administration. They increased the acres planted to the supported crops. Figure 1 illustrates those acreage increases, especially for wheat, corn and soybeans, using USDA-NASS data. Many farmers often borrowed to expand their farming operation, taking on more debt to put more acres into production.

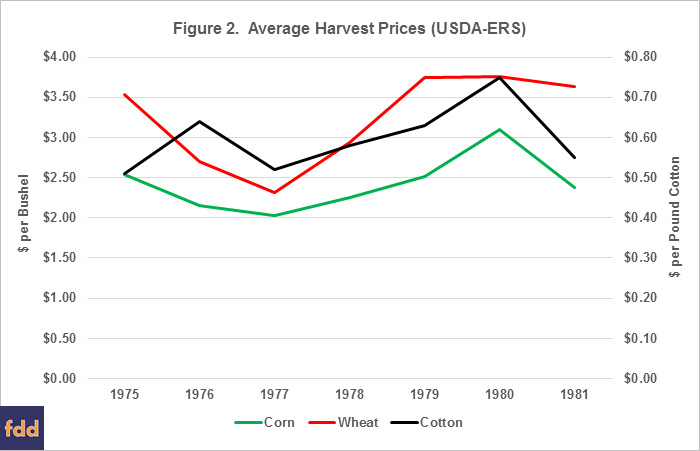

Export markets did not live up to expectations which, coupled with increased production, dampened crop prices. Making matters worse, the Carter Administration instituted embargoes during this era, including a grain embargo on the Soviet Union in December 1979 following its invasion of Afghanistan. Figure 2 illustrates price movements using USDA-ERS average prices at harvest for corn, wheat and cotton from 1975 to 1981.

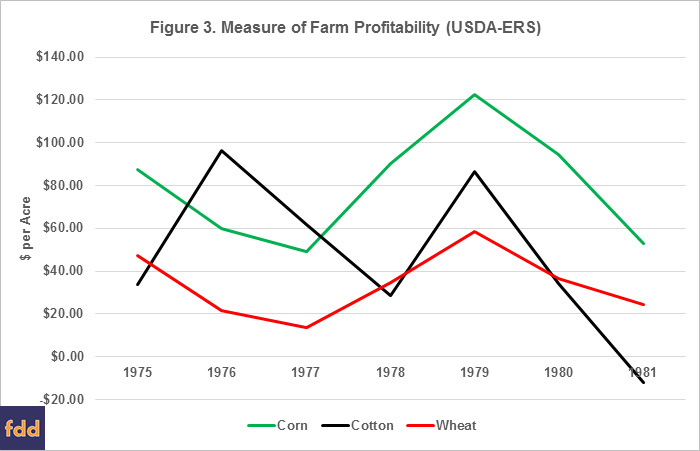

Inflation that included high energy costs and interest rates increased the farmer’s financial burden, which was particularly problematic for the many who had taken on debt to expand. In 1978, for example, farmers made their frustrations with the 1977 Farm Bill clear when they conducted a “tractorcade” on the National Mall. Figure 3 provides a measure of farm profitability from those years using USDA-ERS data to calculate the difference between the gross value of production (average prices and yields) and expenses (variable and fixed cash) for corn, wheat and cotton. Figure 3 illustrates that costs and prices began to take their toll and heavily indebted farmers were rapidly sinking into crisis going into the 1981 debate.

Budget Reconciliation and the Boll Weevil Democrats

California Governor Ronald Reagan defeated President Carter in the 1980 election; Republicans won a majority in the Senate and added 33 seats in the House, although it remained in Democratic control. The newly-elected President prioritized spending and tax cuts. He also called for an end to Federal involvement in farming by eliminating deficiency payments, separating food stamps and terminating many other programs in the farm bill. It was a part of the vision for decreasing the Federal government championed by the President and his team, including Office of Management and Budget Director David Stockman.

Congress had created budget reconciliation in 1974 as part of its efforts to discipline spending, but had used it sparingly. The Reagan Administration and its allies in Congress, especially the Senate, took an innovative approach to reconciliation by requiring fourteen committees to amend existing laws in their jurisdiction to cut spending for fiscal years 1981 through 1983. The Democratic-controlled House concurred, thanks in large part to 40 Southern Democratic Representatives who formed the Conservative Democratic Forum, otherwise known as Boll Weevil Democrats. They were concerned about their own political survival in districts that voted heavily for Ronald Reagan in 1980.

Both the Senate and House Ag Committees had been required to meet the reconciliation instructions. The Senate Ag Committee split the two bills and made substantial reductions to food stamps. The House Agriculture Committee placed caps on food stamp spending to meet its obligation, but Republicans in the House rejected that provision as insufficient. On the floor, they defeated the committee’s provisions with an amendment making specific reductions and were helped by the Boll Weevil Democrats. A total of 29 Democrats (24 from the South) were key to both the budget in May and the reconciliation changes in the substitute amendment in June; Democrats held a 243 to 192 majority in the 97th Congress and could only afford to lose 25 votes.

The 1981 Farm Bill Debate

To get his budget and tax cut priorities through Congress, however, President Reagan had cut a deal with the Boll Weevil Democrats, trading their votes for an agreement to protect Southern commodities in the farm bill process. That deal provoked a backlash against those commodities during the farm bill debate later in the year. The Senate Ag Committee reported a bill that violated budget limits because falling crop prices rendered the committee’s increased target prices too expensive. Fixing them on the floor fueled an intense dispute; Senators nearly eliminated the peanut program and threatened the sugar program.

The farm bill faced even more difficulties in the House, where the committee bill also exceeded budget limits. Representatives voted to end the peanut program and the sugar program, with Republicans helping defeat both programs despite President Reagan’s earlier deal. They spared the tobacco program, however. These (mostly) Southern commodities were victims of a Boll Weevil blowback, retaliation on the floor against Southern Democrats for cutting a deal with Reagan on the budget and tax cuts. The House bill extended food stamps but significant pressure for reforms required a complicated floor compromise.

A difficult conference negotiation produced an agreement that limited increases to target prices and spared the peanut program, but included only a one-year extension of food stamps which heightened Democratic opposition. In the House, backlash against the budget, Boll Weevils and food stamp cuts created a bipartisan coalition of opponents that tried to defeat the bill; they came within two votes of bringing down the conference report.

Relevance for the Upcoming Farm Bill Debate

The most relevant takeaways from the 1981 debates are the coalition dynamics involved in legislating. Spending pressures possess unique ability to unravel a farm bill by splitting apart the coalition. President Reagan’s team had purposefully deployed the budget (i.e., reconciliation) as an offensive weapon. Their goal was to divide coalition interests against each other to enable cuts to both farm programs and food stamps that otherwise might not have been possible. The 2014 Farm Bill debate provided a similar lesson. Forced spending reductions create substantial friction as everyone seeks to protect their priorities and see the cuts taken elsewhere. It is most likely to intensify partisanship over food stamps (now SNAP), as experienced in the 2013 House debate (farmdoc daily, April 17, 2014).

In addition to the budget, the 1981 Farm Bill also provided a lesson in the opposing forces created by a struggling farm economy. Arguably, it was becoming dire enough to pull farm interests back from the brink and allowed them to narrowly escape the trap set by the Reagan Administration. The record indicates that it was not easy in large part because deal-making by the Boll Weevils unleashed a nearly uncontrollable blowback. A functioning coalition is necessary to pass a farm bill but one can just as easily form in opposition, particularly if one interest is viewed as overreaching or cutting deals that harm the others.

For the upcoming farm bill, budget pressures are already evident and could worsen substantially if Congress and the Administration pursue budget reconciliation or otherwise require reductions. The farm economy has also weakened as large crops hold down prices. These competing demands on the farm bill and its coalition are likely to generate conflict at a time of intense partisanship. Added to that is an element that did not exist in 1981: uncertainty as to whether significant damage remains to the coalition after the bruising 2014 effort. As the farm bill process gets underway, the lessons from 1981 might well be of value.

References

Coppess, J. "Reviewing Farm Bill History: the Agricultural Act of 1954." farmdoc daily (7):29, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, February 16, 2017.

Coppess, J. The Fault Lines of Farm Policy (forthcoming, University of Nebraska Press 2018).

Kuethe, T., and J. Coppess. "Mapping the Farm Bill: Voting in the House of Representatives." farmdoc daily (4):70, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 17, 2014.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.