Revisiting Big Corn and Soybean Crops Get Bigger

In the August 2024 Crop Production report, the USDA projected the U.S. average corn yield at 183.1 bushels per acre, which if realized would be a new national record. This projection was raised a half a bushel to 183.6 bushels per acre in the September Crop Production report. The upward trajectory of the USDA projections naturally leads to the question of whether further increases are in store. There is a long-standing market saying that “big crops get bigger and small crops get smaller.” This statement implies that early USDA yield forecasts are “conservative” in years when yields are high and get larger as the forecast cycle progresses and are “optimistic” in years when yields are low and get smaller as the forecast cycle progresses. Some believe that such “smoothing” of USDA yield forecasts, particularly in years of yield extremes, is intentional in order to minimize or spread the price impact of very large or small yields.

The general issue of smoothing of USDA corn and soybean production forecasts was analyzed by Isengildina, Irwin, and Good (2004), and specifically, whether big crops get bigger and small crops get smaller by Isengildina, Irwin, and Good (2013). We updated and extended the analysis of Isengildina, Irwin, and Good (2013) in three earlier farmdoc daily articles (August 20, 2014, September 10, 2014, September 28, 2016). The statistical evidence from this body of work simply does not support the conclusion that big corn and soybean crops get bigger or small crops get smaller. Yet, there continues to be widespread belief that there is substantial truth in the old market adage. The purpose of this article is to update our previous analysis with an additional eight years of observations to determine if our previous findings still hold.

Analysis

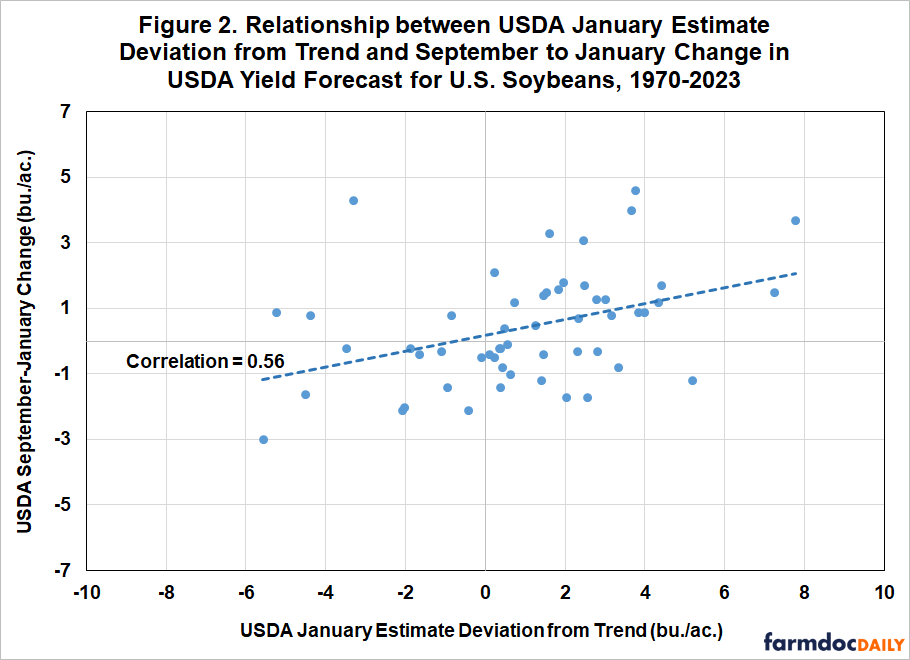

We use U.S. average yield forecasts and “final” January estimates for the 54-year period from 1970 through 2023. A big crop is defined as a crop with an average yield (or yield forecast) above trend value. Trend for a particular year is calculated based on actual U.S. average yield (January estimate) from 1960 through the year prior to the current year. For example, the 1970 trend yield is estimated based on 1960-1969, the 1971 trend yield is based on 1960-1970, and so on. The analysis starts with the traditional (but erroneous) approach to evaluating the “big crops get bigger and small crops get smaller” issue and is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 for corn and soybeans, respectively. Plotted on the horizontal axis is the magnitude of the difference between the final yield estimate released in January and the trend yield calculation for that year. Positive observations indicate the actual yield was above trend (large) and negative observations indicate the actual yield was below trend (small). Plotted on the vertical axis is the magnitude of the change in yields from the September forecast to the January estimate. Positive (negative) observations indicate that the final yield was above (below) the September forecast.

The results are obviously mixed in that the direction and magnitude of the change in yield from September to January varies a lot regardless of whether the January yield estimate is above or below trend. However, the slope of the linear fit of the relationship is positive and the magnitude of the correlation between yield change and the magnitude of the final yield estimate relative to trend is a respectable 0.42 for corn and 0.56 for soybeans (1.0 indicates perfect correlation), which appears to provide concrete evidence that large crops get larger and small crops get smaller. It is not surprising that this relationship leads many to support the notion that large (small) crops get larger (smaller).

So what is wrong with this conclusion? The underlying problem is that at the time the September yield forecast is made, it is not known whether the final yield estimate in January will be above or below trend, or what the magnitude of the yield change will be from September to January. The analysis based on Figures 1 and 2 is backward-looking. Specifically, it addresses the question: Did what turned out to be a big (small) crop get larger (smaller) across the USDA forecasting cycle. This is fundamentally ex post, or after the fact, analysis. The relevant question is instead: Does what appears to be a large (small) crop in September get larger (smaller) by January? The September yield forecast may point to an above or below trend yield, but as observed in Figures 1 and 2, yield estimates can change considerably from September to January so what is believed to be a large or small crop in September may not actually turn out to be true.

Figures 3 and 4 present a forward-looking, or ex ante, analysis of the question about large (small) crops getting larger (smaller). Plotted on the vertical axis for each year is the difference between the September yield forecast and the final yield estimate released in January, the same as in Figures 1 and 2. A positive (negative) value means the January yield estimate was larger (smaller) than the September forecast, the same as in Figures 1 and 2. Plotted on the horizontal axis, however, is the difference between the September yield forecast for each year and the calculated trend yield for that same year. The calculated trend yield each year is the same as that used in Figures 1 and 2. The key difference is that trend yield is subtracted from the September USDA yield forecast in Figures 3 and 4, whereas the trend yield is subtracted from the final January USDA yield estimate in Figures 1 and 2. A positive (negative) observation for the horizontal axis in Figures 3 and 4 therefore indicates that the September forecast was above (below) the trend yield. In sum, the determination of whether the crop is big or small is based on the September forecast rather than the final yield estimate. This is the more relevant analysis since in real-time the only information available at the time is the September monthly yield forecast.

The relationships displayed in Figures 3 and 4 stand in sharp contrast to the results in Figures 1 and 2. The magnitude of the correlation between yield change and the magnitude of the September yield forecast relative to trend is near zero for corn and small, but negative, for soybeans. We also checked whether these results are consistent through time by dividing the 1970-2023 sample in half and re-estimating the correlations. The first half (1970-1996) correlations were 0.19 for corn and 0.09 for soybeans, respectively. The second half (1997-2023) correlations were -0.24 for corn and -0.43 for soybeans, respectively. Note that the second half correlations were actually the opposite of what is expected.

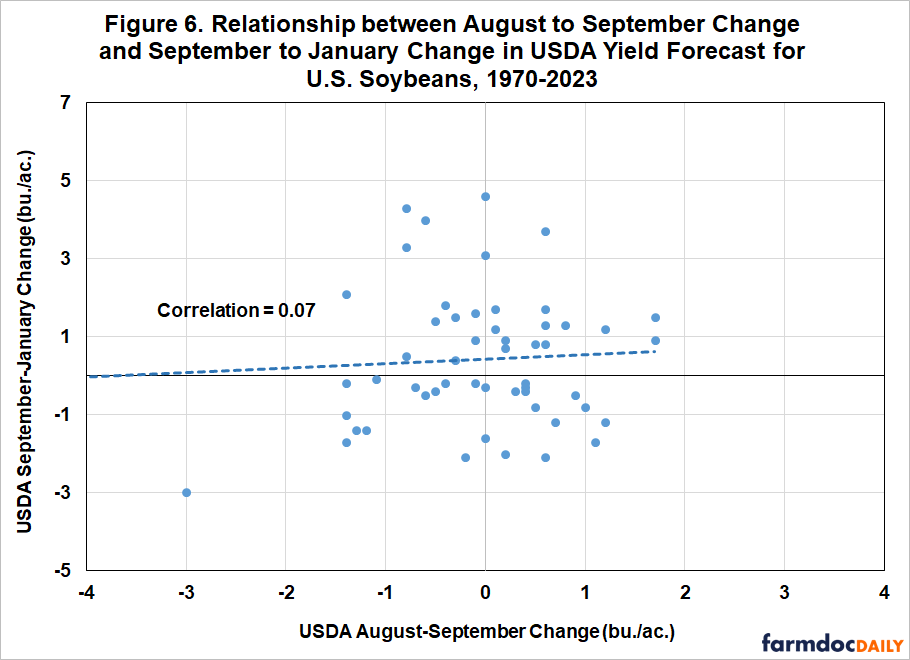

In sum, we confirmed our previous findings that big crops do not necessarily get bigger and small crops do not necessarily get smaller over the USDA forecasting cycle for corn and soybeans. However, there still remains the question of smoothing regardless of the size of the crop, which, as we noted earlier, has been well-documented in the literature (see Isengildina, Karali, and Irwin (2024) for a review). Figures 5 and 6 plot the August to September change and September to January change in USDA corn and soybean yield forecasts over 1970-2023. In corn, there is actually a small positive correlation of 0.27. Essentially this says that about 30 percent of the change in the September to January forecasts can be anticipated based on the direction and magnitude of the August to September change. A much smaller correlation coefficient of 0.07 is reported for soybeans in Figure 6. So, we continue to find some evidence of USDA smoothing in corn production forecasts but more limited evidence in soybeans.

The relationship between USDA yield changes can be quantified in other ways. The previous analysis of the relationship includes both direction and magnitude. Do the results change if only the direction of the relationship is considered? That is, if the USDA August to September forecast change is positive, how frequently does the USDA yield estimate increase or decrease from September to January. Those counts can be made directly from Figures 3 and 4 and are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 for corn and soybeans, respectively.

Panel A of Table 1 shows that the August to September forecast change for corn was positive in 24 years from 1970 through 2023 and negative in 30 years. The September to January yield change was positive in 34 years, or 63 percent of the time. While interesting, these are the unconditional probabilities of whether the forecast changes were up or down. We are interested in the conditional probabilities shown in Panel B. For example, given that the August to September change in the USDA forecast is positive, what is the probability that the September to January change will also be positive? This is computed by dividing 17 in the “up/up” cell in Panel A by 24, the total number of “up” changes for August to September. The resulting conditional probability is shown in Panel B to be 70.8 percent. In other words, if the September forecast is above the August forecast, there is about a 70 percent chance that the final January estimate will also be above the September forecast. It is interesting to note that this tendency is not symmetric, as the conditional probability of the September to January change being negative given that the August to January change is negative (“down/down”), is actually slightly below 50 percent.

The directional relationships for soybeans are shown in Panel A and B in Table 2. In the case of soybeans, the unconditional probability of changes being up or down are near 50 percent, as are the conditional probabilities of September to January changes given the August to September change. There is very little evidence of directional smoothing in USDA soybean yield forecasts.

Once again, we checked whether the directional results are consistent through time by dividing the 1970-2023 sample in half and re-estimating the frequencies. This had little impact on the results. For example, the conditional probability that the September to January change was positive given that the August to September change in the USDA forecast was positive was 75.0 percent in the first half (1970-1996) of the sample and 66.7 percent in the the second half (1997-2023). Conditional probabilities for soybeans remained near 50 percent in both the first and second half of the sample.

Implications

The September 2024 USDA yield forecasts of 183.6 bushels for corn and 53.2 bushels for soybeans are both well above trend and new national records. Some argue that these forecasts will become even larger based on the old adage that “big crops get bigger and small crops get smaller.” The analysis in this article clearly suggests that expectations for the direction and magnitude of change in the USDA yield estimates between September and January should not be influenced by the fact that early (September) forecasts are above trend. The evidence usually cited as justification for this marketing adage is actually backward-looking and biased because it is based on information (final January yield estimates) that is not available in real-time. In other words, the variability of September to January changes in USDA corn and soybean yield estimates is too large in most years to reliably determine whether the crop is truly “large” or “small” early in the forecasting cycle.

While there is no evidence to support the notion that “big crops get bigger and small crops get smaller,” there is a well-documented tendency for USDA crop production forecasts to be smoothed across the forecasting cycle regardless of crop size. For example, we estimate that if the September yield forecast for corn is above the August forecast, there is about a 70 percent chance that the final January yield estimate will also be above the September forecast. Since the September 2024 USDA corn yield forecast was a half-a-bushel above the August forecast, there is a reasonable chance that the final January yield estimate for corn will be above the September forecast.

Finally, a full analysis of yield prospects at this point in the season should be based on a careful analysis of growing season weather conditions, end–of-season crop conditions, August to September changes in USDA forecasts, and early yield results. The USDA’s next Crop Production report to be released on October 11th will provide additional insight into the likely magnitude of the final 2024 yield estimates for corn and soybeans.

References

Irwin, S., D. Good, and J. Newton. "Do Big Corn Crops Always Get Bigger?" farmdoc daily (4):156, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 20, 2014.

Irwin, S. and D. Good. "Big Corn and Soybean Crops Get Bigger is a Myth!" farmdoc daily (6):184, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 28, 2016.

Isengildina, O, S.H. Irwin, and D.L. Good. "Do Big Crops Get Bigger and Small Crops Get Smaller? Further Evidence on Smoothing in U.S. Department of Agriculture Forecasts." Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics 45(2013):95-107.

Isengildina, O, S.H. Irwin, and D.L. Good. "Are Revisions to USDA Crop Production Forecasts Smoothed?" American Journal of Agricultural Economics 88(2006):1091-1104.

Isengildina-Mass, O. B. Karali, and S.H. Irwin. “Are USDA Forecasts Optimal? A Systematic Review.” Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, published online September 23, 2024. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-agricultural-and-applied-economics/article/are-usda-forecasts-optimal-a-systematic-review/FC36FD14D4BE82E1A0D5C9DD45E90280

Newton, J., S. Irwin and D. Good. "Do Big Soybean Crops Always Get Bigger?" farmdoc daily (4):173, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 10, 2014.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.