Squeezing the Farmer, Part 1: Initiating Examination of a Persistent Challenge

Fear not, the 118th Congress has achieved the bare minimum, passing a continuing resolution that funds the federal government through December and avoids a shutdown prior to the election (The Washington Post, updated September 25, 2024; Hubbard, September 25, 2024). Reauthorization of the Farm Bill was not included (White, September 26, 2024). The potential for a lame duck longshot on reauthorization remains in the discussion for an expected post-election session (Abbott, September 25, 2024; Grebner, September 26, 2024). This article opens a series examining a long-recognized and persistent challenge for farmers and farm policy: falling prices and incomes when costs and expenses do not decrease, or do not fall as fast.

Background

Much of the current farm policy debate has been narrowed to the single dimension of crop prices; and, more specifically, whether crop prices are too low and need to be offset by federal payments. This issue has been a significant contributor to the two-year impasse over Farm Bill reauthorization and serves reminders about the problems inherent in reducing complex matters to single, one-size-fits-all solutions. For example, crop prices have fallen during the final months of the current marketing year for last year’s crop and for futures markets for the crop currently being harvested (farmdoc daily, Market Prices). Depressed crop prices are one of the primary risks that farmers manage, but not the only one. The current decline is mostly due to expectations for outstanding harvests and potentially record yields; a further reminder, if one is needed, that a farmer’s revenue is the crop yield multiplied by the prices at which the crop is sold (e.g., 200 bushel per acre corn at $4.50 per bushel is $900 per acre in revenue, while 150 bushel/acre corn sold at $5.50 per bushel is $825 per acre). Declining crop revenues are most concerning for farmers in terms of covering the costs of producing either the harvested crop or next year’s crop, or both (see e.g., farmdoc daily, September 24, 2024; September 20, 2024; September 17, 2024).

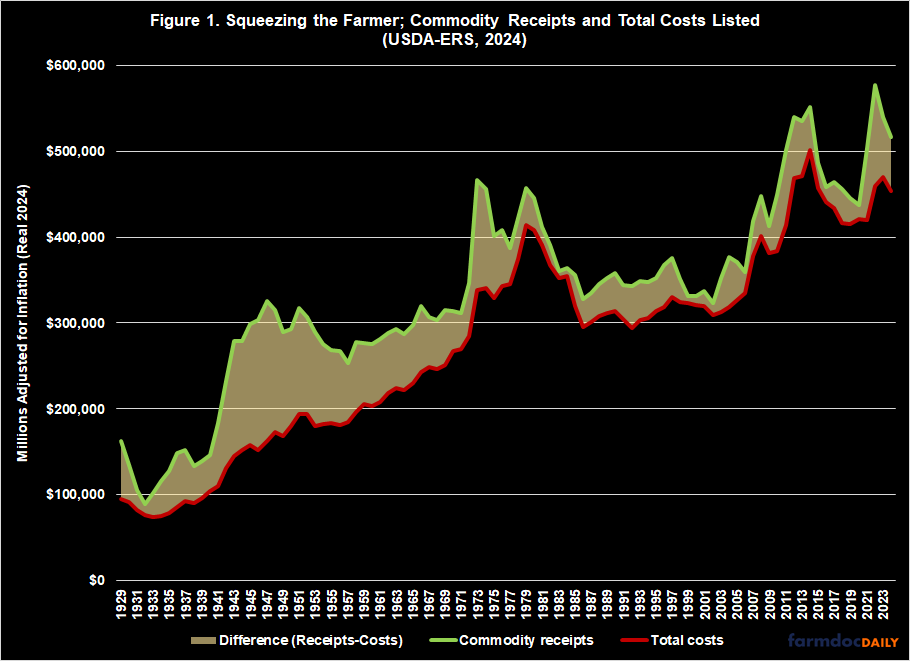

Figure 1 seeks to illustrate the concept of the economic squeeze on farmers. It is adapted from the data reported by USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS); all amounts have been adjusted for inflation by ERS (USDA-ERS, “Data Files: U.S. and State-Level Farm Income and Wealth Statistics”). In Figure 1, the squeeze is represented by the difference between income from farming, or the national total cash receipts from all commodities (crops plus animals and products, light green line), and the national total costs reported (red line). Note that the receipts do not include other sources of income reported by ERS; cash receipts do not include direct governmental payments.

One of the risks of reducing farm policy to a single, narrow dimension is that the policy suffers all of the political problems without delivering real benefits to actual farmers. For example, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the bill reported by the House Agriculture Committee would increase direct spending by $32.973 billion over the ten year budget window (FY2024-2033) (CBO, August 2, 2024; farmdoc daily, August 8, 2024). Total spending on farm program payments was projected to increase $43.376 billion and that $34.949 billion (80.6%) of that increase was the result of raising the reference price thresholds in the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) program. The continued impasse over Farm Bill reauthorization is notable given the decline in crop prices. The entire episode also raises difficult questions because the proposed changes to farm payment programs will bring no relief to farmers at this particular moment; any payments from those changes would not be made until October 2026 (see e.g., farmdoc daily, August 22, 2024; July 18, 2024). In moments such as this, a journey through history could be instructive and the discussion below initiates one through the history of the economic squeeze on farmers.

Discussion

This year marks 100 years since Senator Charles L. McNary (R-OR) and Representative Gilbert N. Haugen (R-IA) first introduced federal legislation to provide direct assistance to farmers to help address what was known as the farm problem. The bill was defeated in Congress that year; it would take until May 1933, in the aftermath of the devastation of the Great Depression, before Congress enacted such assistance in the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 (Benedict, 1953; Coppess, 2018). In the 1933 Act, Congress declared a policy to “reestablish prices to farmers at a level that will give agricultural commodities a purchasing power with respect to articles that farmers buy, equivalent to the purchasing power” in the pre-World War I years, 1909 to 1914 (P.L. 73-10, available from the National Agricultural Law Center). Out of these concepts, Congress and USDA would fashion the parity system of farm policy—price supporting loans coupled with acreage allotments to control production and the potential for marketing quotas—that form the basis of permanent law: the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 and the Agricultural Act of 1949 (farmdoc daily, September 12, 2024). The parity calculation was generally based on a comparative ratio of crop prices and costs.

The focus on purchasing power of commodities before World War II became concerns that farmers could get caught in a “vicious squeeze between rising costs and falling gross income” in the post-war economy (Nowell, 1947, at 144). As Congress worked to enact the Agricultural Act of 1949, Secretary of Agriculture Charles Brannan testified that farmers could be the “major early victims of a squeeze” when crop prices fell (1949 House Ag Hearing, Part 2, at 140; see also, (1949 Joint Committee Hearing, at 218). His concerns were further supported by agricultural economist Theodore W. Schultz who informed a joint committee that “gross farm income is in the process of falling” but “net income is falling more rapidly” and he predicted that this would cause a “squeeze between cost and revenue” that “at some points [] is going to become serious” (at 549). Secretary Brannan produced his own plan for addressing this problem but it quickly became controversial and was ultimately rejected by Congress in favor of returning to the 90% of parity system in the 1949 Act (see e.g., Smith, 1950; Brownlee and Johnson, 1950; Kline, 1950; Jesness, 1950; Coppess, 2018).

The concerns about a squeeze between farm income or revenue and costs continued to be emphasized throughout contentious farm policy debates of the 1950s (see e.g., Morse, June 24, 1953; Graebner, 1954; Keiser, 1956; Fite, 1956). For example, Representative Charles Hoeven (R-IA) speaking on the House floor in 1954 pointed to a 13 percent decline in net farm income since the end of the Korean War, as well as down “25 percent since 1947,” and he argued that “whenever the farmer’s income declines his purchasing power declines, and it is immediately felt by business and industry” (Cong. Rec., June 30, 1954, at 9385). Similarly, Representative Harold Lovre (R-SD) pointed to “a gradual drop in net farm income” since early 1951, and claimed it had “dropped 24 since its peak in 1947” causing “what is known as a cost-price squeeze” (Cong. Rec., June 30, 1954, at 9394).

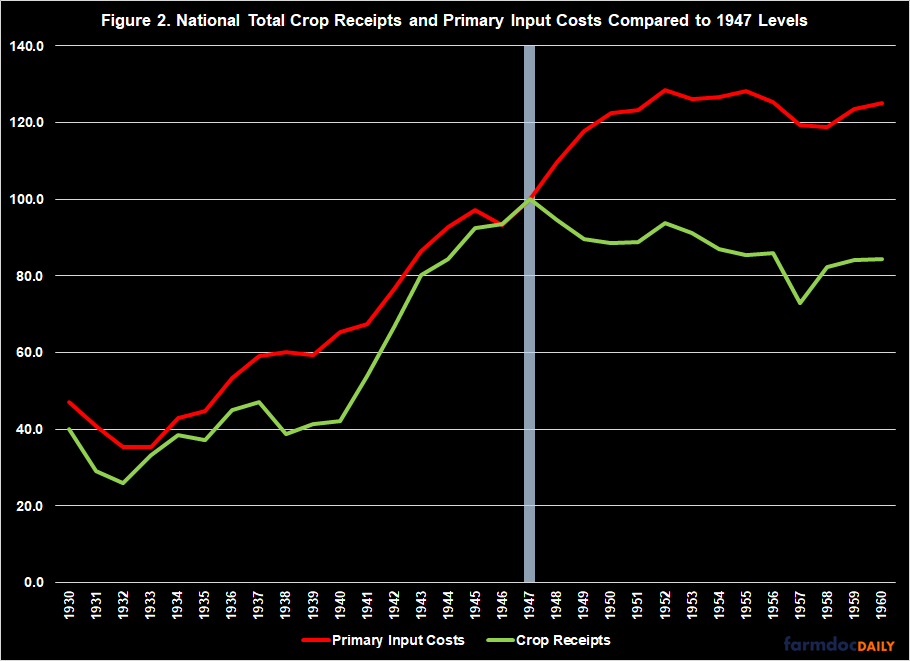

Were the concerns about a squeeze justified? For perspective, Figure 2 illustrates a comparison for the years 1930 to 1960 of the national totals for crop receipts and primary input costs (seed, fertilizer, pesticides, fuel, and electricity), adjusted for inflation and reported by ERS. Both are compared to the levels in 1947, which was the peak for crop receipts and the highest level for the primary input costs up to that year. The space between the lines would seem to justify concerns. Primary input costs continued to increase after 1947 while crop receipts decreased relative to that year.

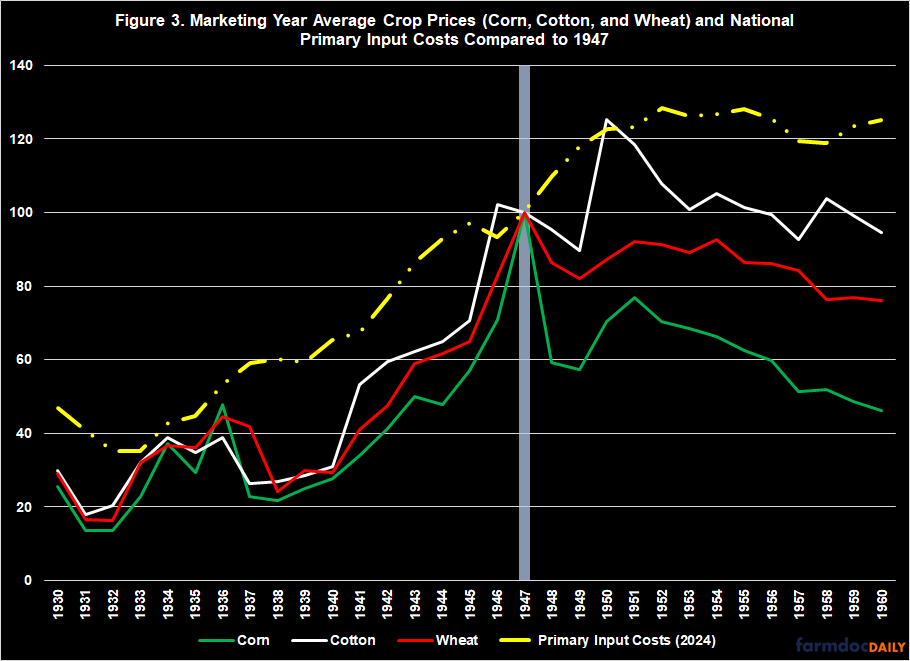

Looking closer, Figure 3 illustrates a comparison of the Marketing Year Average (MYA) prices for corn, cotton, and wheat from 1930 to 1960 to the MYA prices for those crops in 1947, as well as a comparison of the national total primary input costs (seed, fertilizer, pesticides, fuel, and electricity) reported by ERS. Here again is evidence of a squeeze on farmers. Prices generally fell after 1947 but costs continued to increase relative to it.

Figures 2 and 3 provide the jumping off point for examining this issue and the implications for farm policy. It may be notable that farm policy deliberations in the era after World War II were consumed by a narrow—almost singular—focus on high, fixed (90% of parity) loan rates for the program crops. Based on what Figures 2 and 3 appear to indicate, this policy design was likely ineffective for its purpose and the emphasis on it counterproductive, but much remains to be explored.

Concluding Thoughts

At the center of the impasse in Farm Bill reauthorization is a big bet on a single policy: increasing reference prices in the Price Loss Coverage program, which the Congressional Budget Office projects will cost nearly $35 billion over 10 years. Reducing farm policy to a narrow, one-size-fits-all priority carries the real risk of self-destructive political problems with no real benefits to actual farmers. Increasing reference prices will not result in any possible increase in payments until October 2026. Moreover, the change, if it triggers larger payments, could contribute to squeezing farmers if the payments keep costs inflated. There is much here to explore in the days leading to an expected lame duck session of the 118th Congress and this article takes the first step.

References

Abbott, Chuck. “Farm bill is on the lame-duck agenda of House Democrats.” FERN’s Ag Insider. September 25, 2024. https://thefern.org/ag_insider/farm-bill-is-on-the-lame-duck-agenda-of-house-democrats/.

Brownlee, Oswald Harvey, and D. Gale Johnson. "Reducing Price Variability Confronting Primary Producers." Journal of Farm Economics 32, no. 2 (1950): 176-193. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1233100.

Congress of the United States, Joint Committee on the Economic Report. “January 1949 Economic Report of the President.” Hearings. February 8, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18, 1949 (81st Congress, 1st Session).

Coppess, J. "Decline and Fall of Crop Prices; Perspectives for Policy Design, Not Panic." farmdoc daily (14):155, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 22, 2024.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2024: A Mid-Summer’s Review." farmdoc daily (14):133, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 18, 2024.

Coppess, J. "Reviewing the Congressional Budget Office Score of the House Farm Bill." farmdoc daily (14):147, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 8, 2024.

Coppess, J. "The Unfortunately Obligatory Farm Bill Expiration and Extension Discussion." farmdoc daily (14):166, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 12, 2024.

Fite, Gilbert. "The Farm Issue." Current History 31, no. 182 (1956): 218-222. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45309182.

Graebner, Norman. "Farm Welfare, 1954." Current History 26, no. 150 (1954): 111-116. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45308598.

Grebner, Meghan. “Congress targets lame-duck session for farm bill work.” BrownfieldAgNews.com. September 26, 2024. https://www.brownfieldagnews.com/news/congress-targets-lame-duck-session-for-farm-bill-work/.

Hubbard, Kaia. “Congress passes 3-month funding extension to avoid government shutdown.” CBSNews.com. September 25, 2024. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/house-vote-continuing-resolution-government-shutdown/.

Jesness, O.B. "Agricultural Programs—Whither Bound?" Journal of ASFMRA 14, no. 1 (1950): 26-30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43755732.

Keiser, Norman F. "An analysis of the first interim report of the new house subcommittee on family-size farms." Journal of Farm Economics 38, no. 4 (1956): 998-1014. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1234243.

Kline, Allan B. "Government and Agriculture." Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science 24, no. 1 (1950): 78-87. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1173451.

Morse, TRUE D. "The Solid Future for Agriculture." Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1, no. 7 (1953): 506-508. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/jf60007a003.

Nowell, R. I. "The Farm Land Boom." Journal of Farm Economics 29, no. 1 (1947): 130-149.https://www.jstor.org/stable/1232941.

Paulson, N., G. Schnitkey, B. Zwilling and C. Zulauf. "2025 Illinois Crop Budgets." farmdoc daily (14):173, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 24, 2024.

Ratchford, C. B. "Adjustments Farm Families are Taking to the Cost Price Squeeze." (1953). https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/324949/files/1954-2.pdf.

Rollins, Mabel A. "What Farm People are Doing About the" Cost-Price Squeeze"." (1953). https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/324984/files/1954-38.pdf.

Schnitkey, G., N. Paulson and C. Zulauf. "Implications of Non-Increasing Farmer Returns." farmdoc daily (14):168, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 17, 2024.

Smith, Russell. "The Brannan Plan: Counterattack in Favor." The Antioch Review 10, no. 1 (1950): 62-73. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4609394.

The Washington Post. “Senate, House pass bill to avert government shutdown, setting up December fight.” Updated September 25, 2024. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2024/09/25/government-shutdown-vote-live-updates/.

U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Agriculture. “General Farm Program (Testimony of Secretary of Agriculture Brannan).” Hearings, Part 2. April 7, 11, 12, 25, and 26, 1949 (81st Congress, 1st Session).

White, Jared. “Congress avoids shutdown, full farm bill extension not included.” Brownfield Ag News.com. September 26, 2024. https://www.brownfieldagnews.com/news/congress-avoids-shutdown-full-farm-bill-extension-not-included/.

Zwilling, B. "Higher Costs and Lower Grain Prices Lead to Lower Farm Earnings in 2023." farmdoc daily (14):171, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 20, 2024.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.