Reviewing the Congressional Budget Office Score of the House Farm Bill

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently released the official cost estimate for the Farm Bill reported by the House Agriculture Committee in May (CBO, August 2, 2024; House Agriculture Committee, H.R. 8467). An official cost estimate is typically a critical procedural requirement in the legislative process pursuant to Congressional budget rules. Cost estimates also provide valuable transparency on provisions in complex omnibus legislation like the Farm Bill. This article reviews CBO’s analysis of the House Farm Bill.

Background

In review, Congress created the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in 1974 to operate as a non-partisan, unaffiliated resource for objective analysis on budget and economic matters. Over time, Congress has changed budget policy to increase its disciplinary nature and operation, placing overwhelming emphasis on reducing spending. Among the many developments, Congress required CBO to project 10-year spending estimates to create an annual baseline, as well as requiring CBO to score legislative changes against the baseline over one-, five-, and ten-year budget windows regardless of the length of the authorization (2 U.S.C. §639; 2 U.S.C. §907; CBO, April 18, 2023 (cost estimates); and April 18, 2023 (baseline); see also, farmdoc daily, June 6, 2024; March 23, 2023; February 13, 2020; July 18, 2019; April 18, 2019; November 29, 2018). The 118th Congress, moreover, added a provision known as “CUTGO” which prohibits consideration of any legislation that increases mandatory spending within either a six-year or 11-year window (House, January 10, 2023, Rule XXI, clause 10; Heniff, CRS, May 9, 2023). The score of the House Farm Bill provides an example of being unwilling to live by Congress’ own rules.

Discussion

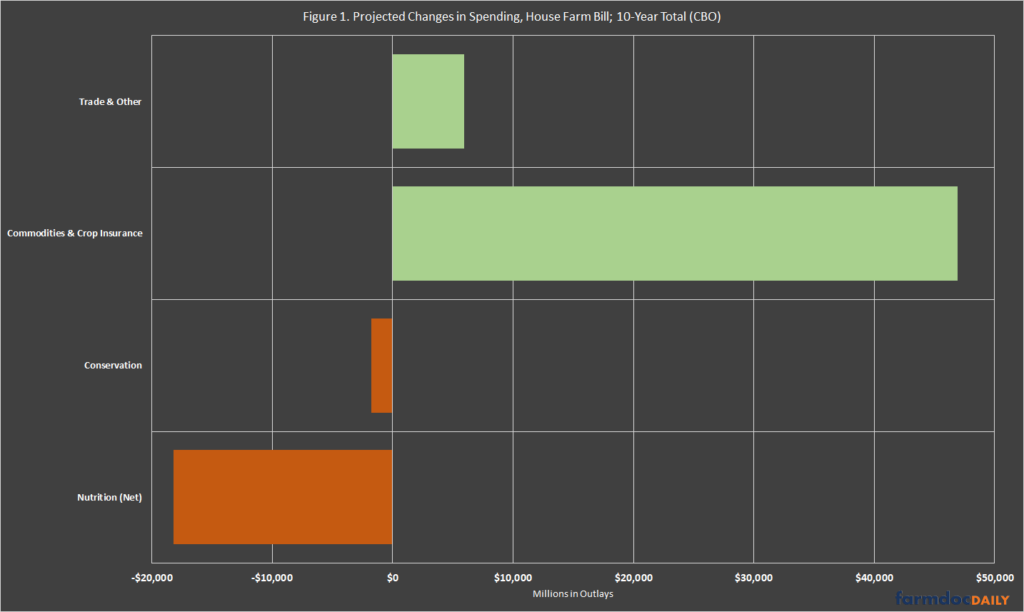

Overall, CBO projects that the House Farm Bill will increase mandatory spending by $33 billion over 10 years. Figure 1 illustrates the 10-year total changes in spending projected by CBO. Note that CBO scored the changes against the May 2023 baseline, not the more recent June 2024 baseline (CBO, May 2023; June 2024).

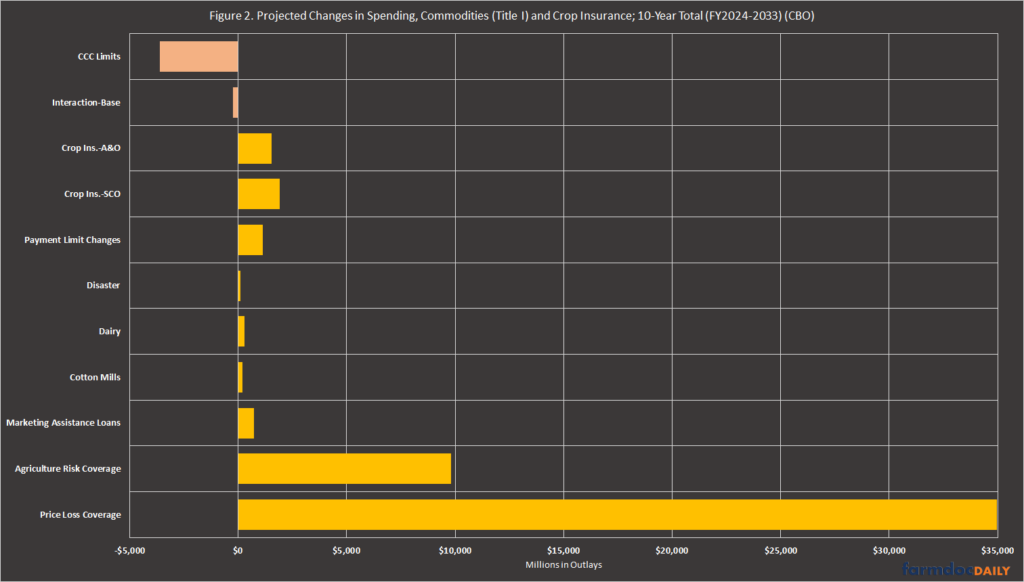

Clear in Figure 1, almost all additional spending in the House Farm Bill is for the farm programs in Title I and Crop Insurance; almost all reductions in spending are from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), with minor scored reductions for conservation programs. If enacted, CBO estimates that the House would spend an additional $47 billion over 10 years as compared to the May 2023 baseline: $43 billion for Title I; and $3.5 billion for crop insurance. Figure 2 illustrates the ten-year total spending projections for these programs. Notably, most of the additional spending is for increasing reference prices in the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) program: $35 billion. CBO scored the limitations on Commodity Credit Corporation authorities as saving only $3.6 billion over 10 years, or about one-tenth of the total cost for increasing reference prices.

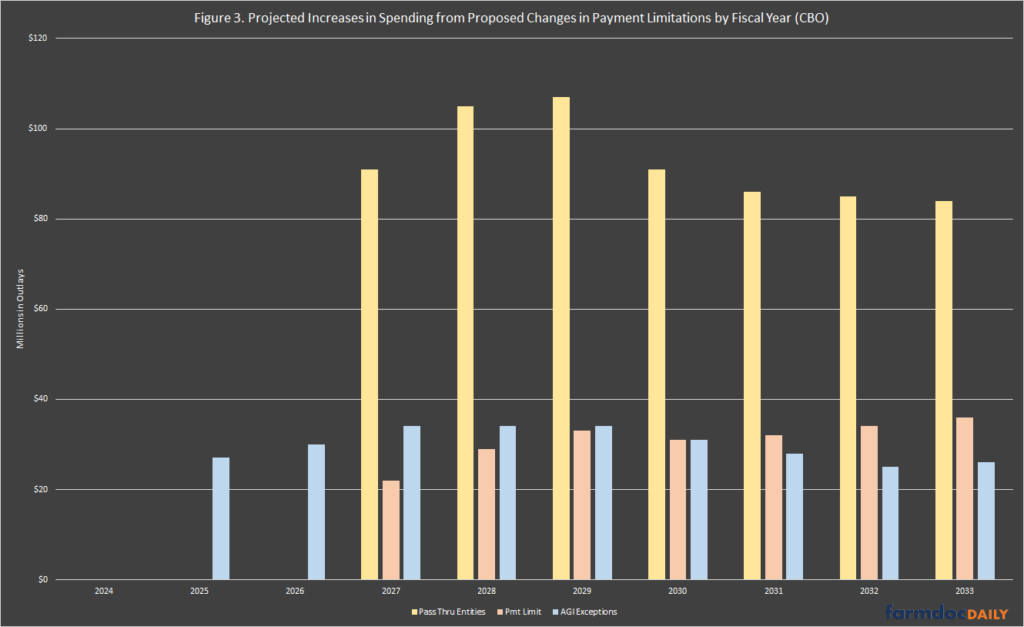

The CBO score highlights other notable changes that have received less attention. The House Farm Bill would increase spending on farm program payments through changes in the methods for limiting payments and for eligibility. First, the House would permit farmers to receive additional payments through “qualified pass through entities” which includes partnerships, limited liability companies (LLC), S corporations, and joint ventures or general partnerships. Second, the House Farm Bill increases the payment limit from $125,000 to $155,000 with future increases to adjust for inflation. This applies only for those operations with 75% of adjusted gross income (AGI) from farming, ranching, or silviculture activities. Third, the House exempts conservation program payments, supplemental disaster payments, and payments from the Noninsured Crop Assistance Program (NAP) from the $900,000 AGI requirement if the operation demonstrates that 75% or more of income is from farming, ranching, or silviculture activities. In total, CBO projects that these changes will cost $1.1 billion over the next 10 years. Figure 3 illustrates the additional spending from these changes for each of fiscal years 2024 through 2033.

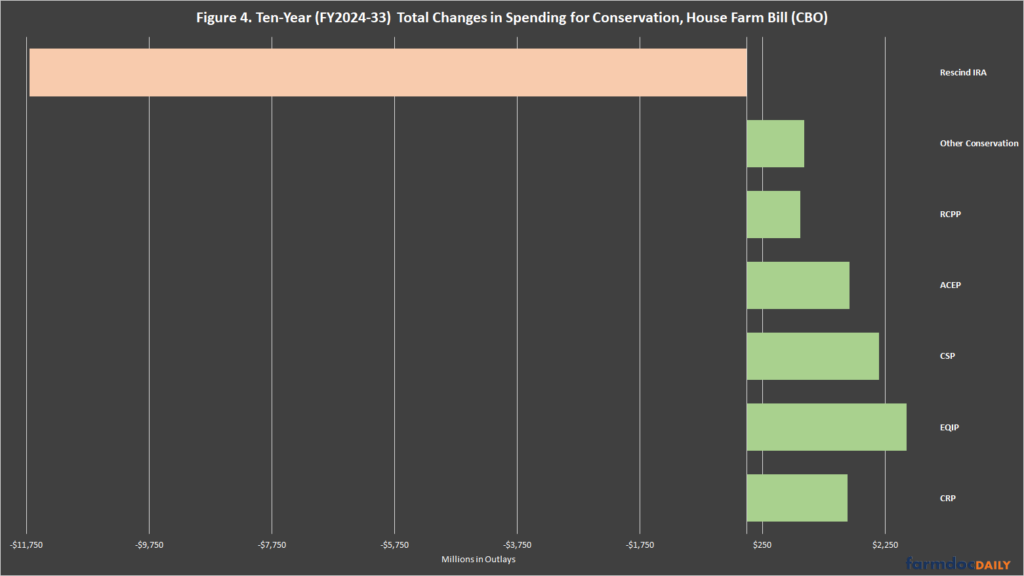

For conservation, the House Farm Bill proposes to rescind the additional investments from the Inflation Reduction Act, which provided $18 billion for the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), the Agriculture Conservation Easement Program (ACEP), and the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP). CBO projects that this would reduce spending by $11.7 billion over ten years. The House Farm Bill reinvests most of those funds by increasing the baseline line for conservation programs. In total, CBO projects increased spending of just under $10 billion through the Farm Bill conservation authorizations, which is nearly $2 billion less than the savings from rescinding the IRA investments. Figure 4 illustrates the CBO score for these changes.

For conservation programs, budget authority is also important because it represents the funding available to USDA for payments to farmers and CBO scoring is different than for commodities and crop insurance. Congress authorizes fixed amounts from the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) each fiscal year, such as $2.025 billion for EQIP (see, 16 U.S.C. §3841). CBO projects outlays from that budget authority that typically is less for many of the near-term fiscal years (e.g., $1.6 billion in FY2023, $1.7 billion in FY2024, etc.). CBO projections of outlays are not limits on USDA obligations but are for scoring purposes. In total, Congress increased total budget authority for EQIP by $8.45 billion in the IRA, compared to the House Farm Bill increase of $3.325 billion; for CSP, the IRA budget authority increase is $3.25 billion compared to the House Farm Bill increase of $3.125 billion. The changes in the House Farm Bill present a tradeoff for conservation funding: Increased BA is permanent whereas the IRA funds are available only through FY2031. With the House Farm Bill, there are fewer conservation funds in the near term, but the increased budget authority will eventually provide more conservation funding over the long term. Whether that tradeoff is worth it for farmers is a question for further exploration, especially in light of the increased costs for farmers adopting conservation due to the recent period of inflation (see, farmdoc daily, May 23, 2024).

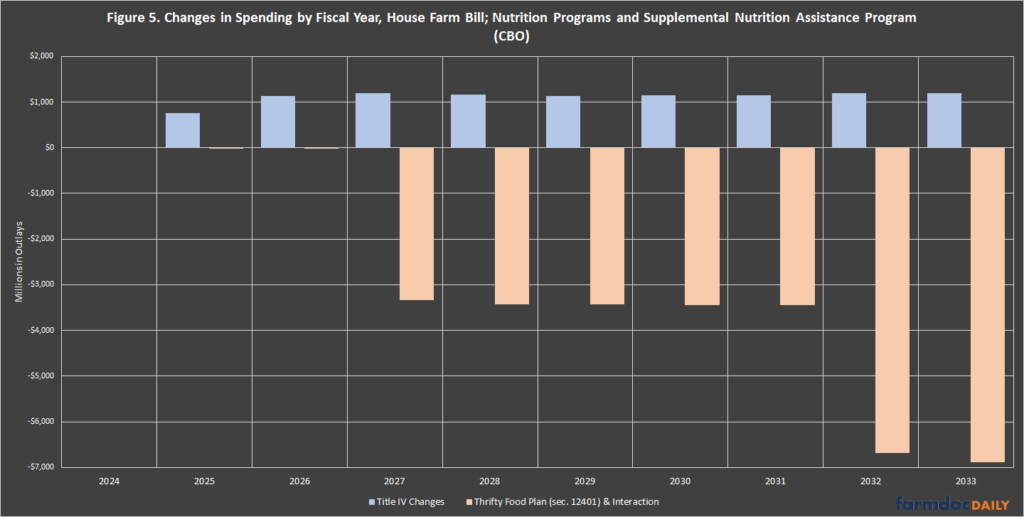

Finally, Figure 5 illustrates the changes in spending by fiscal year for Nutrition programs in the House Farm Bill. Note that these changes are in two different titles. The House Farm Bill increases spending through a myriad of changes in Title IV, which CBO projects to total $10 billion over ten years (FY2024-2033). Buried in Title XII, the miscellaneous title, however, are the controversial changes to the Thrifty Food Plan calculations for food assistance. CBO projects that these changes will reduce spending by almost $31 billion over 10 years (FY2024-2033).

The net effect of the two different sets of changes in the House Farm Bill is a $20.6 billion reduction in SNAP assistance. Proposed reductions in SNAP are controversial in any reauthorization debate and have nearly derailed the last two reauthorizations. They become more problematic coupled with the increased spending on farm program payments, including through allowing additional payments through entities and an increase in payment limits, that were not offset.

Concluding Thoughts

As the days of August fall from the legislative calendar, the chances that the 118th Congress reauthorizes the Farm Bill diminish exponentially. CBO costs estimates are typically critical pieces of the reauthorization puzzle, while also providing useful transparency about complex legislation. This transparency can cut through the jumble of amendments, insertions, and deletions of legislative text to provide real insight about the potential impacts of proposed changes to policy; in the wake of a CBO score, there are fewer places left to hide. Such is the case with CBO’s score of the Farm Bill reported by the House Agriculture Committee, exposing the likely increases in farm program payments juxtaposed against reductions in food assistance for low-income households. Either alone may present near-insurmountable barriers to Farm Bill reauthorization but combined sound the death knell for it.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.