Farm Bill 2024: A Mid-Summer’s Review

The already-slim chances of Farm Bill reauthorization in 2024 are wilting in the summer heat, facing a legislative calendar almost out of days. Congress has made no substantive progress since the House Agriculture Committee reported its bill just before Memorial Day. In June, Senator John Boozman (R-AR), the Ranking Member on the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry Committee (Senate ANF), released a series of one-page summaries of the committee’s Republicans’ “framework” for the Farm Bill that generally traced the bill reported in the House (Senate ANF, Minority News, June 11, 2024). By late June, Senate ANF Chairwoman Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) called for a “Time To Get Real” on Farm Bill reauthorization (Senate ANF, Majority Blog, June 24, 2024). Finally, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released the 2024 baseline projections (CBO, June 2024). This article provides a midsummer’s review for a Farm Bill reauthorization going nowhere fast (see also, farmdoc daily, May 21, 2024; May 29, 2024; May 30, 2024; June 4, 2024; June 6, 2024; June 12, 2024; June 13, 2024; July 17, 2024).

Background

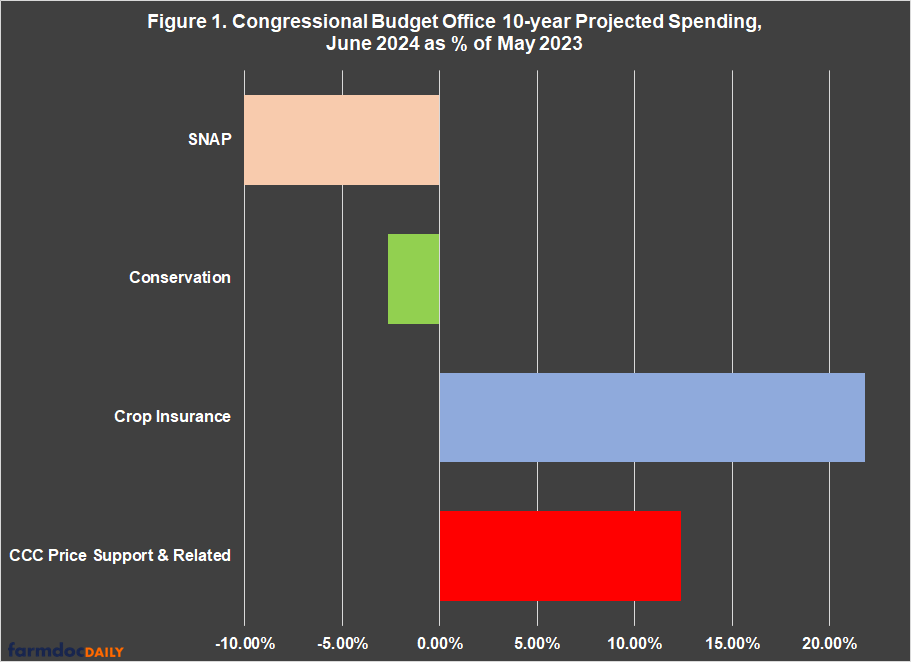

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports spending and revenue projections over a 10-year budget window, known as the baseline, releasing the latest baseline on June 18, 2024 (2 U.S.C. §907; CBO, About CBO: Processes; CBO, June 18, 2024; CBO, Details About Baseline Projections for Selected Programs, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and USDA Mandatory Farm Programs). For the Farm Bill, the new 10-year spending projections (FY2025 to FY2034) in the June 2024 baseline are $1.375 trillion, compared with $1.468 trillion in the previous spending projections (FY2024 to FY2033) reported in May 2023. Figure 1 compares the 10-year spending projections by CBO in the June 2024 baseline to the 10-year projections in the May 2023 baseline. Note that spending projections for SNAP and conservation have decreased while those for CCC price support and related (this includes farm program payments) and crop insurance have increased.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is projected to cost $1.1 trillion of total spending in the June 2024 baseline (FY2025 to FY2034), a decrease of over $120 billion from the May 2023 baseline ($1.223 trillion). By comparison, total farm policy spending increased in the June 2024 baseline compared to the May 2023 baseline, going from $245 billion (FY2024 to FY2033) to $276 billion (FY2025 to FY2034). Spending on farm program payments and other support programs increased from $83.6 billion to nearly $94 billion (112%) and spending on crop insurance increased from $101 billion to $123.4 billion (122%), while 10-year spending on conservation is projected to decrease from $60 billion to $58 billion (97%).

Discussion

CBO spending projections are just that: projections 10 years into an unknowable future using economic models with the assumption that current law does not change during the decade. Changes in baseline projections are not available as savings or offsets but are also not charged against policies. CBO uses the baseline projections for scoring purposes as increases or decreases in costs from changes proposed by legislation, such as Farm Bill reauthorization.

(1) Marketing Year Average Price Projections and Reference Prices

The Marketing Year Average (MYA) price projections for the program crops are used to project the costs of payments to farmers who have base acres of the covered commodities. These projections figure most prominently in the estimated costs of increasing the statutory reference prices that trigger payments in the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) program, but also impact projected costs of payments from the Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) program. In the June 2024 baseline, CBO generally projects slightly higher MYA prices for all major program crops except sorghum.

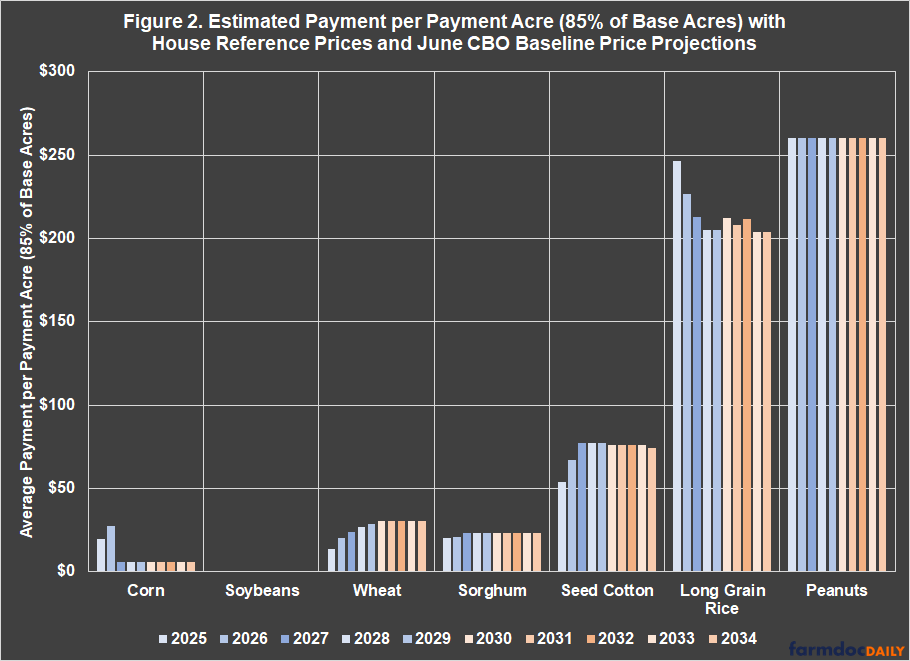

The Farm Bill reported by the House Agriculture Committee in May contained large increases to the statutory reference prices for some program crops and much smaller increases for others, although all crops received an increase (farmdoc daily, May 21, 2024). The framework summaries released by the Senate ANF Republicans did not contain specific reference price increases, indicating only an “average” increase of 15% (Senate ANF, Republican Framework: Title I—Commodities). Figure 2 applies CBO’s June 2024 MYA price projections for the major program crops to the House Farm Bill’s increased statutory reference prices to calculate the average payment per payment acre (85% of base acres). Note that the blue bars are for the years of a Farm Bill authorization (2025 to 2029) and the red bars are for the outyears after the Farm Bill would be scheduled to expire.

In Figure 2, the House Farm Bill’s reference prices would increase the disparity among farmers based on CBO price projections. The effective value of base acres for each of the major program crops under the House Farm Bill as estimated by average payments per acre over the 10-year baseline are: peanuts, $260.10; long grain rice, $213.64; seed cotton, $73.24; wheat, $26.69; sorghum, $22.88; corn, $9.60; and soybeans, $0.04. Little justification has been provided for these vastly different base acre values among farmers who plant (and insure) many of the same crops; therein lies much of the problem for reauthorization.

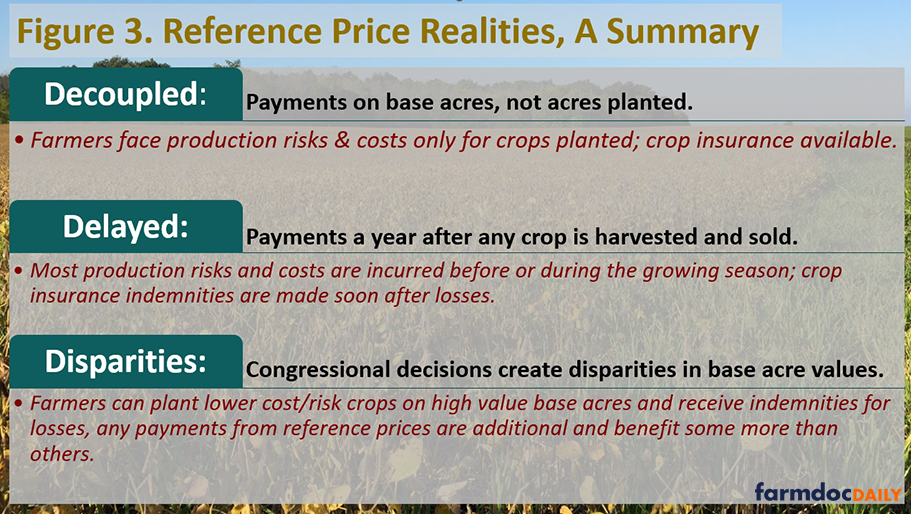

The reality of reference prices differs drastically from the political arguments made on their behalf. Reference prices are merely payment delivery mechanisms, not risk management tools; more problematically, they represent political decisions to benefit some farmers more than others. As summarized in Figure 3, reference prices are decoupled, delayed, and come with real disparities. Any payments they trigger are made on base acres, not the acres a farmer planted and for which there is actual risk; likewise, any costs of production for specific crops are irrelevant when payments are decoupled. Additionally, any payments are made a year after a crop was harvested and marketed, well after any costs or risks were incurred. Such payments cannot assist farmers with crops not planted, nor with any costs incurred well before any payments. Inflation experienced in 2021 or 2022, for example, will not be addressed by payments made in October of 2025, especially for crops that the farmer did not plant. The payments do present real potential problems, however, because they could well impact future costs, especially cash rents (see e.g., farmdoc daily, August 31, 2023). When made, payments hit the farmer’s bank accounts around the time the next season’s costs are likely to be booked and cash rents negotiated. Setting reference prices too high is more likely to feed inflationary pressures in the future rather than provide assistance for costs in the past, especially on crops not planted.

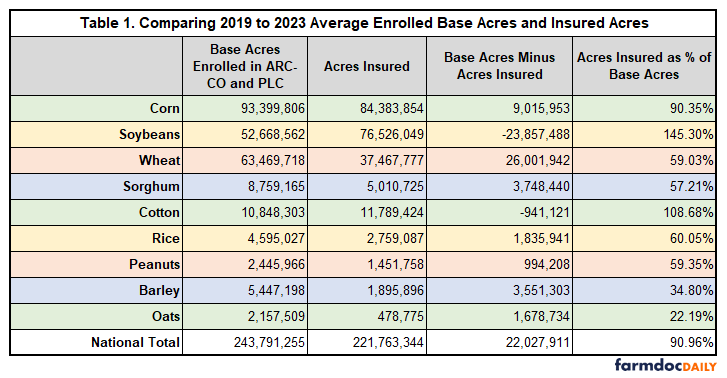

Because payments are decoupled from planting decisions, farmers can receive disparate payments while planting and insuring the same crops. Reference price decisions in Congress impact the value of the base acres, allowing farmers with high value base acres to plant other crops, especially crops with lower costs or risk, and take out crop insurance on the crops planted. Under that reality, a farmer can receive crop insurance indemnities for losses on crops planted while also receiving payments on base acres that have no relation to the crop planted, providing an additional cash benefit to those with the more valuable base acres. Of course, some portion of this is due to annual crop rotations. Comparing acres insured to the major program crops with base acres offers significant insights. Table 1 begins that exploration by comparing the national average base acres enrolled in ARC-CO and PLC with the average acres insured for the major program crops from 2019 to 2023, compiled from the data reported by USDA (FSA, ARC/PLC Program Data; RMA, Summary of Business).

Note that each year (on average) about 40% of rice base and peanut base—the highest value base acres in terms of payments—are planted and insured to other program crops, most likely soybeans. This will vary from year-to-year, but it is a benefit only available to southern farmers with base acres of these crops.

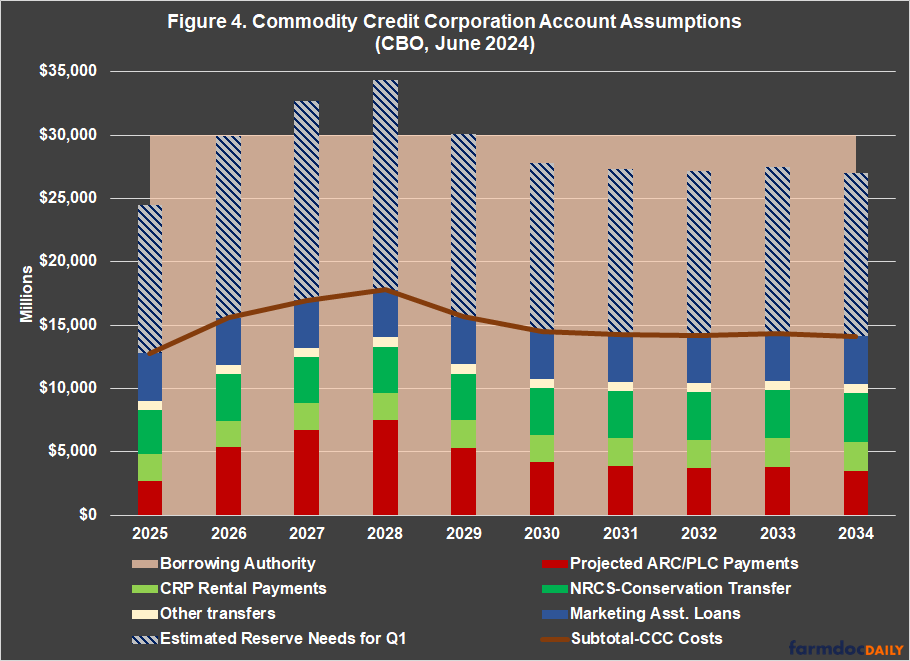

(2) The Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) Account

The House Agriculture Committee’s Farm Bill also picked a budget fight over limiting the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) authorities, claiming that the limit would cover the costs of the reference price increases. This issue raises many questions, not the least of which being the consequences for any possible floor consideration (see e.g., farmdoc daily, June 6, 2024). CBO’s June baseline adds yet another twist, detailing for the first time the projected spending from the CCC account, as well as the implications for the $30 billion borrowing authority cap and annual replenishment by Appropriators (CBO, Details About Baseline Projections for Selected Programs, USDA Mandatory Farm Programs). Figure 4 illustrates the information reported by CBO. Critical is the $30 billion statutory borrowing authority, a limit placed in the CCC Charter Act by Congress (USDA, CCC Charter Act). Timing is also important; in the first quarter (Q1) of the fiscal year, CCC funds are used for farm program payments, conservation payments (including transfers to NRCS), and Marketing Assistance Loans (MAL). CBO reports that the new FY costs are booked in Q1 before an Appropriation to replenish the account has been applied. This effectively doubles the amounts necessary under the borrowing authority in the FY and, in at least 2 years, exceeds that authority. By increasing the costs of farm program payments, the House Farm Bill would make this problem worse. It also makes clear why CBO cannot, under current conditions, score much of an offset from the provision in the House Farm Bill.

It has been a long time since a Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) issue resonated in American politics; for history fans, the CCC last made a notable political appearance in the 1948 presidential election. Congress had enacted the charter act that June but included a provision limiting CCC authority to purchase or lease storage—a provision reportedly demanded by commercial grain dealers opposed to what they viewed as potential government-backed competition. On the campaign trail, President Truman accused Republicans in Congress of having “stuck a pitchfork in the farmer’s back” because, he argued, the provision they enacted amounted to a backdoor method for eliminating price supports (Coppess, 2018, at 81-82; Matusow, 1970, at 178-81).

Concluding Thoughts

For all intents and purposes, the previously slim chances of a Farm Bill reauthorization process in 2024 or by the 118th Congress have become nonexistent. That process, considered regular order, involves committees marking up legislation and reporting it to the respective chamber floors, where the legislation is considered and, if passed, goes to conference for final agreement and legislative text before passing both chambers again and going to the President’s desk for signature. The legislative and political calendars are effectively closed to such a time-consuming effort. All that remains is an outside chance that some negotiated outcome can be salvaged for a potential lame duck session after the November elections. It is more likely that any lame duck session will merely extend the 2018 Farm Bill again. Given the current state of Congress and American politics—something the elections are unlikely to remedy and may make worse—it may be prudent to ask whether any extension should be for multiple years instead of just one.

Stepping back to survey the wreckage of reauthorization reveals a primary cause: the long-unspecified demand to increase reference prices. After more than a year, the House Agriculture Committee produced an imbalanced set of increases but without a viable offset for the costs. The offset proposed was not sufficient, leaving the committee to attack CBO scorekeepers rather than adjust the proposal to comply with Congressional budgetary requirements. While the House Agriculture Committee did manage to report a bill, that legislation lacks a viable path with the budget and political problems facing it: tens of billions in projected farm payment costs that are not offset, coupled with strong opposition to the proposed reductions in spending for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). On the Senate side, nearly the entire 118th Congress has passed without any specifics on raising reference prices other than Chairwoman Stabenow’s proposal for a five percent increase for just three crops (seed cotton, rice and peanuts). Ranking Member Boozman’s June framework continued the practice of avoiding specifics; such reticence is not conducive to successful legislative outcomes, but the scoring problems in the House probably explain it.

More concerning, however, is the extent of further damage to the Farm Bill coalition. By attacking SNAP assistance while seeking to increase farm program payments once again, 2024 will mark the third consecutive Farm Bill reauthorization effort in the House to take this troubled route. In addition, the effort raised concerns for conservation and crop insurance. The House bill appears designed to alienate almost all possible political allies beyond the narrowest faction of farm interests. Rummaging through history for perspective turns up comments by the late Senator Richard Lugar (R-IN). He once referred to fixed price policy (then target prices, now reference prices) as “ticking time bombs” and a “strange preoccupation” with “no particular philosophy” beyond diverting federal funds to particular commodities and States (see, Coppess, 2018, at 154 and 213-14). While he was mostly concerned with the budgetary implications, this third straight reauthorization mess expands the scope: here is a policy with some federal budget challenges but that has proven highly destructive to the Farm Bill coalition. In this, a sector vital to society is reduced to the narrowest possible scope with crass means deployed to rapacious ends. Risk management is valuable but steady streams of large payments—funds that flow far from farm fields—are likely to do more harm than good to actual farmers.

What explains the current state of Farm Bill politics other than cynicism? What actual farmer benefits from any of this, or from such unreasonable expectations? Who won by betting it all on an unreasonable, unpaid-for, and politically untenable demand for boosting benefits to the fewest farmers?

Disagreement is fundamental to politics and policymaking, in part because it is core to resolving substantive matters for achieving legislative outcomes. Neither disagreement nor argument shuts down policymaking; rather, it is the failure to deliberate honestly, negotiate in good faith, and compromise fairly to achieve outcomes in the public interest (see e.g., Waldron, 1999; Waldron, 2004). Well-reasoned deliberation is critical to the public interest. Where accountability is shrouded in silence, only circumstantial evidence speaks volumes. This includes fundamental disagreements cast as disloyalty and discord, displaced with performative grievances and anonymous attacks in compliant media, along with other well-worn tactics of special interests funding enforcers of fealty.

Is it minor in the grand scheme of things or is a third consecutive reauthorization fiasco a symptom of what is ailing the American body politic? Today’s Farm Bills were gifted a broad, powerful legislative coalition that crossed many of the fault lines in American politics and could once surmount Madison’s double majority with relative ease (see e.g., farmdoc daily, January 12, 2023). It now appears unable to cross the starting line without collapsing on itself in a heap of self-inflicted absurdities. Minor matters may provide much-needed clarity to diagnosing the mortal disease that so troubled the Framers’ minds (see e.g., farmdoc daily, November 11, 2022). Of course, it all may risk diagnosis of a more Shakespearean kind. As farm bill eyes focus on the lame duck longshot, these questions and more linger in the interregnum whether they are welcome or not. Among other things, it remains to be seen whether this pursuit of increasing reference prices becomes allegorical, a strange version of killing the goose that laid the golden eggs.

References

Aesop. “The Goose & the Golden Egg.” Available from the Library of Congress, https://read.gov/aesop/091.html.

Coppess, J. "Budgetary Dissonance and the 2024 House Farm Bill." farmdoc daily (14):106, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 6, 2024.

Coppess, J. "Considering Congress, Part 2: The Mortal Disease of Self-Government." farmdoc daily (12):170, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, November 11, 2022.

Coppess, J. "Considering Congress, Part 4: The Double Majority." farmdoc daily (13):6, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, January 12, 2023.

Coppess, J. "History and the 2024 House Farm Bill." farmdoc daily (14):102, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 30, 2024.

Coppess, J. and J. Hutchins. "Farm Bill 2023: Is There Bad Medicine in Base Acres and Reference Prices?" farmdoc daily (13):158, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 31, 2023.

Coppess, Jonathan. The Fault Lines of Farm Policy: A Legislative and Political History of the Farm Bill (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018).

Matusow, Allen J. Farm Policies and Politics in the Truman Years (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967. Reprint, New York: Atheneum, 1970).

Schnitkey, G., B. Sherrick, C. Zulauf, N. Paulson, J. Coppess and J. Baltz. "Farm Bill Proposals to Enhance Supplemental Coverage Option (SCO)." farmdoc daily (14):104, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 4, 2024.

Schnitkey, G., J. Coppess, N. Paulson, B. Sherrick and C. Zulauf. "Spending Impacts of House Proposal for Commodity Title Changes." farmdoc daily (14):96, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 21, 2024.

Schnitkey, G., J. Coppess, N. Paulson, C. Zulauf and B. Sherrick. "Cotton STAX and Modified Supplemental Coverage Option: Concerns with Moving Crop Insurance from Risk Management to Income Support." farmdoc daily (14):111, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 13, 2024.

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow.” Excerpt available from the Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56964/speech-tomorrow-and-tomorrow-and-tomorrow.

Waldron, Jeremy. Law and Disagreement (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Reprint, 2004).

Waldron, Jeremy. The Dignity of Legislation (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Zulauf, C., G. Schnitkey, J. Coppess and N. Paulson. "Are Changes in Cost of Production and Statutory Reference Prices Related in the House Agriculture Committee 2024 Farm Bill?" farmdoc daily (14):101, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 29, 2024.

Zulauf, C., G. Schnitkey, N. Paulson and J. Coppess. "Commodity Program Base Acre Update: Overlooked Issues." farmdoc daily (14):110, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 12, 2024.

Zulauf, C., J. Coppess, N. Paulson and G. Schnitkey. "Crop Insurance and Statutory Reference Prices." farmdoc daily (14):132, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 17, 2024.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.