Farm Bill Stalemate, Part 3: Conservation Concerns

The conservation title is traditionally one of the least controversial and partisan of the major, mandatory funding titles in a farm bill debate; that the conservation title is part of the current stalemate adds to the concerns about the 2018 farm bill. The House version of the farm bill eliminates the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) (farmdoc daily, July 19, 2018). Eliminating CSP and other conservation issues adds to the discussion about assistance to commodities in part 1 of this discussion (farmdoc daily, September 27, 2018). It also compares to the concerns for the farm bill coalition as a whole highlighted by the disputes over the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in part 2. (farmdoc daily, October 4, 2018). As such, part 3 of this discussion of the 2018 farm bill stalemate reviews the concerns about changes to conservation programs and policy.

Background Review

The Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) are the primary working-lands conservation programs in the farm bill. Working-lands program refer to providing conservation assistance on productive farmland rather than taking acres or fields out of production for conservation purposes. Figure 1 illustrates spending on these two programs compiled from CBO Baseline reports, as well as CBO’s projections from the April 2018 Baseline. It demonstrates the historic growth in both EQIP and CSP, and the very different programmatic outcomes under the House and Senate farm bills for CSP and EQIP (green and red lines with dots and dashes).

Approximately $6 billion per fiscal year in the 10-year baseline (FY2019 to 2028) are invested in a suite of conservation assistance programs reauthorized in the farm bill; two of those programs are EQIP and CSP (farmdoc daily, April 12, 2018). Other programs include the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) and the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP), both of which retire or reserve acres out of active farm production for conservation purposes; and the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) that works across other conservation programs on a coordinated, regional basis.

Discussion

Eliminating CSP is arguably the key difference between the House and Senate farm bills. The House farm bill does not eliminate stewardship contracting authority completely, rather shifts the authority to EQIP and reduces its funding. A comparison of the significant differences in funding for multi-year stewardship contracting authority helps illustrate the different vision for conservation policy. It is not, however, the only disagreement or concern with provisions in Title II of the House and Senate farm bills. The following discussion highlights some of the challenges for conference negotiations in the conservation title.

(1) Reduction in Stewardship Contracting Investments

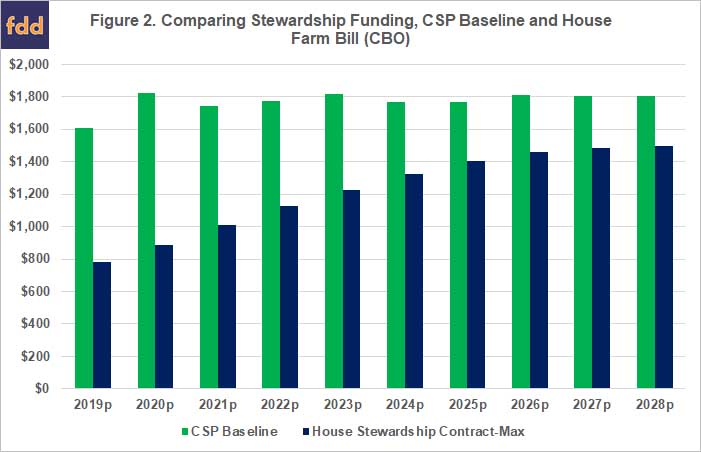

By eliminating CSP, the House farm bill raises an issue about the value of multi-year annual contract payments for stewardship on working lands. The House shifts stewardship contracting authority to EQIP but the funding for crop stewardship activities is limited to a maximum of 50% of the total budget authority provided to EQIP. Notably, this is an upper limit and stewardship contract funding could be less than 50% of the total. Thus, the merging of CSP into EQIP and the 50% cap would result in at least a $5.5 billion reduction over 10 years in the funds available for working land stewardship contracting authority as compared to the CSP Baseline. Figure 2 breaks down stewardship contracting investments by comparing the CSP April 2018 Baseline with the maximum available in the House’s version contained within EQIP.

The Senate farm bill also reduces funding for CSP stewardship contracts, potentially sending a signal that this policy may be losing political support. The Senate impact would be much less by comparison, however. The Senate continues CSP but reduces the acres added each fiscal year from 10 million in the 2014 Farm Bill to 8.8 million per fiscal year. CBO estimated that this would reduce CSP spending by $1 billion over the 10-year budget window (CBO Cost Estimate, June 21, 2018).

(2) Diversion of Working Lands Conservation Funds to Non-farm Entities

In addition to eliminating CSP (House farm bill) or reducing its acres and funding (Senate farm bill), another issue with both versions of the farm bill involves the inclusion of authority that permit irrigation districts and another non-farm entities to compete for the limited funding in EQIP. Under existing law, EQIP provides cost-share assistance to help agricultural producers comply with local, State, and national regulatory requirements, or to avoid the need for regulatory programs, with assistance to install and maintain conservation practices (16 U.S.C. §3839aa). In other words, the funding authorized in EQIP is only for farmers pursuant to current law; that changes if the provisions in either of the House or Senate farm bill is adopted in conference.

Specifically, the House farm bill permits payments to irrigation districts or associations, as well as drainage districts updating systems for irrigation efficiency (H.R. 2, §2302(c), Engrossed in House). The payments can be for structural practices, to provide for water conservation, or transition to water conserving crops or rotations. It also provides for waiver of payment limitations on payments to these entities.

The Senate farm bill also adds authority to make payments to irrigation districts, groundwater management districts or similar entities. It provides for “a streamlined contracting process to implement water conservation or irrigation practices under a watershed-wide project that will effectively conserve water, provide fish and wildlife habitat or provide for drought-related environmental mitigation” (H.R. 2, §2303(5), Engrossed Amendment Senate).

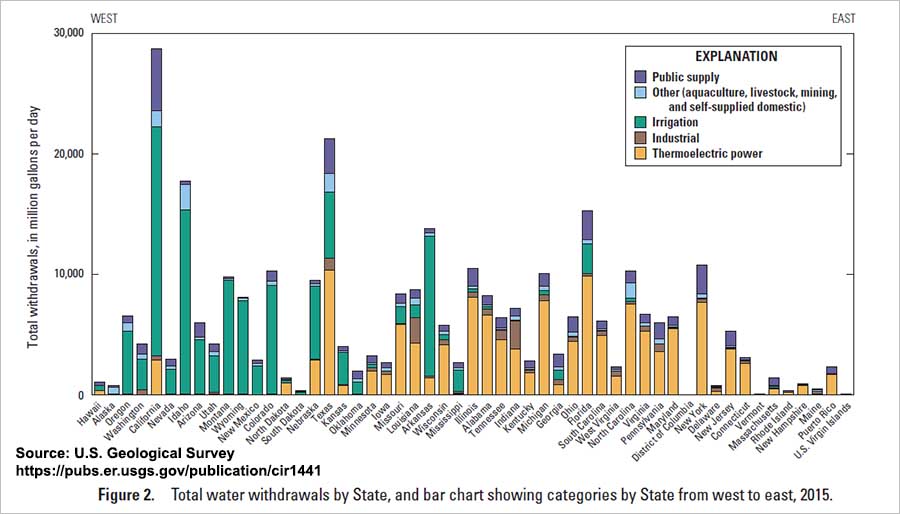

Important for conference negotiations and the current stalemate, permitting irrigation entities to compete for limited EQIP funding has regional implications. States in the Southwestern region of the country—from Texas to California—are the states where irrigation is concentrated, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS, Circular 1441). The image below is from the most recent USGS report on water use in the United States, based on 2015 data (figure 2 in the USGS report).

In addition, permitting irrigation districts and similar entities to seek EQIP payments is a shift in authority that will result in these entities competing directly with farmers for the limited funds authorized in the program. It could also permit duplicative assistance to irrigated farmland; farmers with irrigation can receive EQIP funds as can their irrigation districts, potentially increasing funds for those farmers and regions, while working against conservation priorities in other regions. At this stage of the debate, however, too little information has been provided to adequately estimate the risk to conservation priorities in other regions. Similarly, too little information is currently available to evaluate how it would alter the state-by-state distribution of EQIP funds. It is, however, enough to generate significant concern in states and regions that are not irrigated.

(3) Base Acres and Reduction in Payments for Not Planting

A third issue with the House farm bill crosses both Title I commodities support and Title II conservation assistance. Specifically, the House provides that base acres in ARC/PLC that have not been planted to any covered commodity from 2009 to 2017 will be no longer eligible to receive payments from ARC or PLC (H.R. 2, §1112 (c), Engrossed in House). It is understood that this provision provides a budgetary offset for the increased spending in the House farm bill’s regionally-specific program yield update (farmdoc daily, October 2, 2018; September 27, 2018).

The base acre provision also presents potential conservation concerns because it is likely that base acres that haven’t been planted in those years have been returned to grass cover for pasture and conservation purposes. These are likely to be acres that are not suited to intensive row-crop production but this provision could add pressure on farmers and landowners to return those acres to production. This could, in particular, put pressure on expanded production in the region of the country where the Dust Bowl took place. At a time when prices are low, bringing acres back into production would be counterproductive to market price challenges as well.

Figure 3 is an attempt to better locate where farms are more likely to be impacted by the House provision restricting payments on unplanted base. Figure 3 compares the average acres planted to all covered commodities from 2009 to 2017 (including acres planted to cotton) with the 2015 base acres for that county (including generic base acres) (USDA-FSA: Crop Acreage Data, 2009-2017 crop year files; 2014 and 2015 Base Acres by County). CRP acres, however, are not included because the House bill does not specify how those acres would be treated and more information is needed regarding CRP acres. Figure 3 provides one estimate of the counties where base acres were under-planted to program crops, on average, in those years. These are the counties more likely to have farms impacted by this language. The exact impact would be FSA farm-specific, however. More data and analysis is needed to better understand the location of farms could lose payment eligibility due to this provision.

A further conservation concern is that the House farm bill discounts average rental payments for CRP contracts. The House farm bill does increase the CRP acreage cap from 25 million acres in 2019 to 29 million acres in 2023, which represents an increase over the 2014 Farm Bill cap of 24 million acres. The House farm bill, however, reduces rental rates for acres that are re-enrolled in CRP. Specifically, the House would set first time CRP enrollment contracts at 80% of the estimated average county rental rate. For the first re-enrollment, the rental rate would be at 65% of the average, followed by 55% for the second re-enrollment, 45% for the third re-enrollment and 35% for the fourth re-enrollment (H.R. 2, §2205 (c), Engrossed in House). The Senate, by comparison, increased the CRP acreage cap to 25 million acres and limits rental payments to 88.5% of the estimated county average rental rate, among other changes (H.R. 2, §2104, Engrossed Amendment Senate).

Presumably, this reduces costs of the program and helps cover the added spending necessary to increase the acreage cap to 29 million acres. It also likely reflects a political decision about the relative value of the acres that have been enrolled in CRP for decades, but the House does not provide justification or information on that decision. The provision does raise concerns about whether it will have any impact on soil conservation and erosion concerns on those acres. Such concerns would be magnified if the base acre language adds further pressure to return acres to production in particularly sensitive areas of the country.

Concluding Thoughts

This series has discussed the three primary reasons that the 2018 farm bill reauthorization has reached a stalemate in conference between the House and the Senate. Crop and regional issues over changes to the commodities programs at a time of relatively low prices is one of those reasons. The partisan dispute over changes to food assistance for low-income families is the most contentious and difficult of the issues. And, as discussed herein, changes to conservation policy and spending are the third.

As the conference stalemate drags on, the interactions among these three issues also cannot be overlooked. Successful farm bills have long been built on a large coalition that is bipartisan, spans different production regions of the country and bridges between rural and non-rural interests; much of it a balance among farm programs, conservation and nutrition. The House farm bill in particular challenges this coalition in unprecedented ways by upsetting this balance. Cotton, rice and peanuts—crops grown almost exclusively in the southern states and Republican Congressional districts—stand to benefit disproportionately from the Title I program changes. The irrigated regions of the Southwestern states are also likely to benefit the most from changes to conservation policy and spending, especially elimination of CSP and allowing irrigation districts to compete for funding. This shift in benefits is likely at the expense of the Midwestern and Eastern regions and as compared to water quality conservation important to drinking water concerns for rural communities and urban areas alike. This is a notable concentration of the farm bill’s benefits to one region of the country with an overwhelming partisan affiliation. It represents a significant narrowing of the coalition, exacerbated by the partisan dispute over low-income food assistance in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); a troubling situation for the current stalemate that might have long-term implications for future farm bills.

References

Congressional Budget Office, Cost Estimate, “S.3042, Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018,” June 21, 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/54092.

Coppess, J., C. Zulauf, N. Paulson and G. Schnitkey. "The Farm Bill Stalemate, Part 2: The SNAP Question." farmdoc daily (8):184, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, October 4, 2018.

Coppess, J., C. Zulauf, G. Schnitkey and N. Paulson. "The Farm Bill Stalemate, Part 1: Commodity Assistance." farmdoc daily (8):180, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 27, 2018.

Coppess, J., C. Zulauf, B. Gramig, G. Schnitkey and N. Paulson. "Conferencing Conservation: Reviewing Title II of the House and Senate Farm Bills." farmdoc daily (8):133, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 19, 2018.

Coppess, J., G. Schnitkey, N. Paulson and C. Zulauf. "Reviewing the CBO Baseline for 2018 Farm Bill Debate." farmdoc daily (8):65, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 12, 2018.

Dieter, C.A., Maupin, M.A., Caldwell, R.R., Harris, M.A., Ivahnenko, T.I., Lovelace, J.K., Barber, N.L., and Linsey, K.S., 2018. “Estimated use of water in the United States in 2015: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1441,” 65 p., available online, https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1441/circ1441.pdf.

Schnitkey, G., N. Paulson, C. Zulauf and J. Coppess. "Yield Updating and the Current Versions of the Farm Bill." farmdoc daily (8):183, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, October 2, 2018.

USDA Farm Services Agency, Crop Acreage Data, 2009-2017 crop year files, https://www.fsa.usda.gov/news-room/efoia/electronic-reading-room/frequently-requested-information/crop-acreage-data/index.

USDA Farm Services Agency, “2014 and 2015 base acres by County” data file, October 4, 2018, available online, https://www.fsa.usda.gov/programs-and-services/arcplc_program/index.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.