The Conservation Question, Part 9: The Arrested Development of the Conservation Security Program

Farm Bill reauthorization remains stalled at the starting line in Congress—neither agriculture committee has produced legislative text, let alone scheduled a markup. The rapidly closing legislative calendar for 2023 is devoid of any opportunities for consideration of a bill if the committees could move one; an extension is the only option (Adragna, November 10, 2023; Sholtes, Caitlin, and Carney, November 9, 2023; Hill, November 9, 2023; Sloup, November 7, 2023; Clayton, November 6, 2023; Elbein, November 6, 2023). A one-year extension of the 2018 Farm Bill, however, does little to resolve the fundamental problems plaguing reauthorization. Among them a self-inflicted dilemma befuddles the farm bill coalition and rapidly approaches absurdity: some farm interests want to increase the potential for payments, but the projected costs (not actual payments) have led them towards a proposal to take funding from food assistance and conservation investments. Such a move sets farmers in direct opposition with critical members of the farm bill coalition, including other farmers. This situation raises intriguing political questions that return to the conservation question last discussed three years ago (farmdoc daily, February 27, 2020). The arrested development of the first version of CSP adds further context to the shrinking of its current version (farmdoc daily, October 12, 2023). The saga of CSP also offers additional historical context to the current debate about eliminating conservation funding from the Inflation Reduction Act to cover the costs of increasing the payment triggers for the Price Loss Coverage program (see e.g., farmdoc daily, November 7, 2023; October 26, 2023; October 5, 2023; September 14, 2023).

Background

The Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002 remains an historical anomaly: to date, it is the only farm bill provided additional baseline funding since budget controls took over the legislative process in the early 1980s. The Agriculture Committees in 2001 negotiated an increase of $73.5 billion (over 10 years) for that farm bill. The deal was the direct result of another historical anomaly: for a few years at the end of the 1990s, the federal government ran a budget surplus in which revenues exceeded spending. The budget surplus was short-lived, but the deal for the Farm Bill remained and the result was the 2002 Farm Bill, signed into law by President George W. Bush on May 13, 2002 (P.L. 107-171). The Congressional Budget Office projected that the new Farm Bill would spend more than $80 billion above the March 2022 baseline (CBO, May 6, 2002; CBO, May 22, 2002). Figure 1 illustrates the division of that extra spending among the major titles of the bill: farm programs (71%); conservation (18%); Food Stamps (9%); and all other (3%).

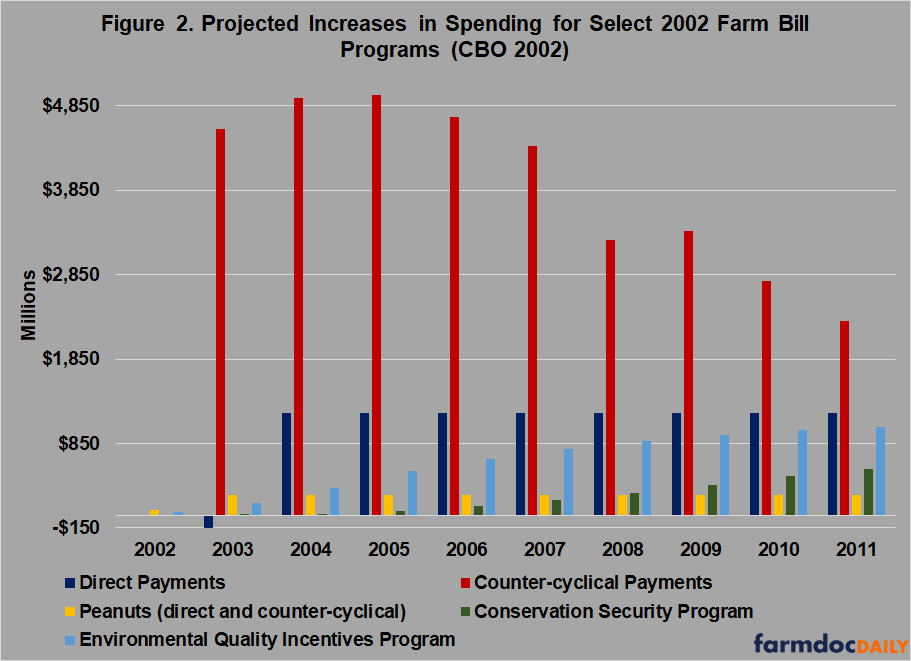

This is only part of the story, however. Beneath the topline budget projections, Congress made significant changes to farm and conservation policy. First, Congress continued the fixed annual contract payments that had been the primary feature of the 1996 Farm Bill, renaming them Direct Payments. The annual payments were projected to increase farm program spending by $9.5 billion. Congress also reinstated the fixed-price farm payment policy designed around target prices and renamed the Counter-cyclical Payments program. Reinstating this policy provided for the largest increase in spending by adding $35.3 billion in projected payments. Among conservation spending was an increase to the funding for the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) of $6.4 billion. Most notably, however, was the creation of an entirely new working lands conservation program called the Conservation Security Program (CSP). CBO initially projected that CSP would cost a total of $2 billion over the 10-year budget window. For context, the total projected costs of CSP were just shy of the total amount projected for peanuts ($2.25 billion). Figure 2 illustrates the CBO projections for increased spending by these programs.

Discussion

The Conservation Security Program (CSP) was initially written in the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry Committee by chairman Tom Harkin (D-IA). Senator Harkin was CSP’s undisputed champion, its author, and the force behind getting it enacted; he first introduced the “Conservation Security Act” in 1999. It was a complex program that provided for three tiers of multi-year (between 5 and 10) annual payments. The contracts with producers were in return for adopting conservation practices and addressing natural resource concerns on their farms. It provided a potential conservation or green alternative to Direct Payments. More importantly, CSP in 2002 was funded through the Commodity Credit Corporation’s mandatory authorities rather than annual appropriations and written without any acreage cap (like the Conservation Reserve Program) or funding limit (like EQIP). CSP was, to say the least, unique among conservation programs in farm bill history. It provided annual payments like a commodities program and was intended to encourage widespread adoption of conservation, rather than seek to remediate natural resources through individual practices or land retirement; a vision of rewarding a more environmentally focused farming (see e.g., Evan 2005).

The additional baseline funding for a farm bill presented a real opportunity for innovation in policy; for conservation, innovations could move the policy beyond land retirement to supporting conservation and farming combined. It was also an acknowledgment that adopting conservation practices on the farm has real costs both financial and managerial, including the time and effort required to implement, maintain, and manage the practices, as well as some level of additional risks. One troubling reality of conservation not previously addressed (nor adequately since) is that adopting new practices could easily place a farmer at a competitive disadvantage. The competitive disadvantages that could result from adopting conservation were also exacerbated by federal farm policy designed to align with prices and production, which could punish a farmer who had taken on conservation voluntarily; neither land retirement nor sharing part of the (estimated) costs of a practice were sufficient for the actual challenges a farmer faced.

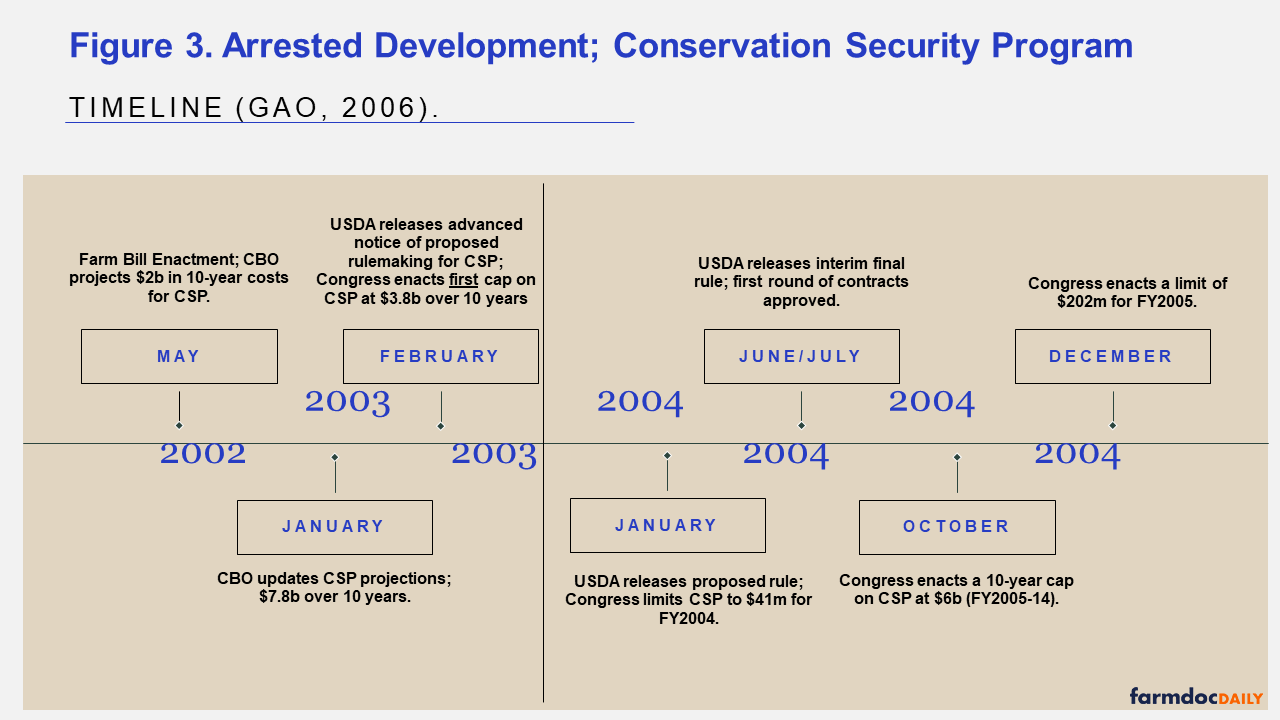

In 2001 and 2002, the farm economy was again struggling against economic headwinds and low crop prices. As indicated in Figures 1 and 2 above, the opportunities for conservation were only partially realized as Congress poured the vast majority of the additional funding back into farm program payments and, especially, the fixed-price triggers of the CCP. CSP came out of the 2002 Farm Bill fight at a lean $2 billion (over 10 years) in the CBO score. It did not take long, however, for even that limited promise to be dashed upon the rocks of political realities. Enacted in May 2002, USDA did not announce the first sign-up until fiscal year 2004 and contracts were first approved in July 2004. Before it began, the budget and politics would arrest the development of CSP and drastically curtail its promise and potential. A 2006 report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) provided significant pieces of evidence but not the full story (GAO, April 2006).

Before it had implemented the program or conducted a single signup, Administration officials informed CBO that they anticipated much greater program participation. In response, CBO increased its spending projections for CSP. In January 2003, CBO increased the program’s costs to $7.8 billion (over 10 years). CBO followed that with a second increase in program cost projections in March 2004, this time to $8.9 billion. By that time, however, Congressional Appropriators had already made their moves. In February 2003, Congress enacted a cap on CSP of $3.8 billion over 10 years, using the savings to cover the costs of emergency assistance to farmers suffering from drought (P.L. 108-7). In January 2004, Congressional Appropriators eliminated the $3.8 billion (10-year) cap on CSP and instituted a one-year limit on the program of $41.4 million (P.L. 108-199); later, in October 2004, appropriators instituted a new ten-year cap on CSP of $6 billion (FY2005-14). Each time CSP was cut, the savings were used to offset emergency disaster assistance for farmers (P.L. 108-324). In December 2004, appropriators placed another one-year cap on the program at $202 million for fiscal year 2005 (P.L. 108-447). Finally, appropriators added yet another cap of $259 million for fiscal year 2006 in November 2005 (P.L. 109-97), followed by a new ten-year cap of $5.65 billion for fiscal years 2006 to 2014 (P.L. 109-171). The series of funding cuts to CSP were unusual because Congress rarely offsets emergency spending and it is controversial to reduce mandatory spending for temporary needs. Figure 3 provides a timeline highlighting these events.

The unusual and controversial limits on CSP’s funding by appropriators altered the vision for the policy as it was enacted. The series of confusing, uncertain funding issues complicated implementation. For example, when USDA finally opened the program, it did so on targeted watersheds rather than as a nationwide program as had been intended in 2002. The first sign-up was for only 18 watersheds in 22 states; only 2,200 farmers enrolled in the program that first year, at a cost of $34.6 million. Implementation on a limited watershed basis notably caused an uproar from farmers and damaged the program in the eyes of those it was supposed to help. Congress took funding available to all farmers and used it to offset the emergency costs of disaster assistance for some farmers. Maybe more problematically, limited operation on a watershed basis because of the funding limits pitted farmers against each other. Sometimes, it was neighboring farmers where those in the watershed could enroll and receive additional payments, while those just outside the watershed could not. The program never recovered and had to be rewritten—and renamed—in the 2008 Farm Bill.

Concluding Thoughts

The conservation question confronts an understanding of the legislative process that can be more idealistic than realistic. Public policy in a system of self-government should work to produce outcomes that benefit the broadest public interest. Farm programs and conservation programs like CSP both provide assistance to farmers, but conservation programs also deliver more direct benefits to the broadest public interests. The willingness of policymakers to sacrifice the broader interests for the narrower interests presents fundamental challenges; the closer one looks, the more troubling and persistent the questions. Just over 20 years have passed since the arrested development of the Conservation Security Program and policymakers once again face decisions over whether to eliminate investments in farm conservation. Differences in the times sharpen the questions: then farmers were struggling with low crop prices and farm programs that did not respond to price declines; now high crop prices have delivered record farm incomes and reduced or precluded farm program payments, while farm programs are responsive to changes in crop prices and will automatically increase payment triggers. Public policy requires justifying changes in policy to the public, including against the burdens of past decisions like those reviewed here. It is not possible to quantify the benefits to farmers and the general public that were lost when CSP was cut back before it could begin. It is possible to learn from the previous episode and work towards better outcomes.

References

This article was adapted from Between Soil and Society: Legislative History and Political Development of Farm Bill Conservation Policy by Jonathan Coppess by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. © 2024 by Jonathan Coppess. Available wherever books are sold or from the Univ. of Nebraska Press (800) 848-6224 and at https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/.

Andragna, Anthony. “All eyes are on Mike Johnson for his plan on how to avoid a government shutdown.” Politico.com. November 10, 2023. https://www.politico.com/live-updates/2023/11/10/congress/house-gop-shutdown-johnson-speaker-00126560.

Clayton, Chris. “Farm Bill Programs Need an Extension: House Ag Chair Agrees Long-Term Extension Needed for Farm Bill.” DTN-Progressive Farmer. November 6, 2023. https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/news/article/2023/11/06/house-ag-chair-agrees-long-term-farm.

Coppess, J. "Reference Prices and the CBO Gamble; Some Additional Context." farmdoc daily (13):197, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, October 26, 2023.

Coppess, J. "The Incredible Shrinking of the Conservation Stewardship Program." farmdoc daily (13):187, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, October 12, 2023.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023: Don’t Look Now, but Reference Prices Will Increase." farmdoc daily (13):182, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, October 5, 2023.

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023: Trying to Reason with 1,000 CBO Scores." farmdoc daily (13):167, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 14, 2023.

Elbein, Saul. “Farm Bill faces battle as GOP pushes to strip climate, SNAP funding for subsidies.” The Hill. November 6, 2023. https://thehill.com/policy/equilibrium-sustainability/4292953-farm-bill-battle-gop-push-crop-subsidies-climate-snap-funding/.

Even, William J. “Green Payments: The Next Generation of US Farm Programs.” Drake J. Agric. L. 10 (2005): 173.

Hill, Meredith Lee. “Behind closed doors, Johnson sounds a cautious note on SNAP.” Politico.com. November 9, 2023. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/11/09/johnson-house-gop-snap-00126341.

Schnitkey, G., N. Paulson, C. Zulauf and J. Coppess. "Price Loss Coverage: Evaluation of Proportional Increase in Statutory Reference Price and a Proposal." farmdoc daily (13):203, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, November 7, 2023.

Scholtes, Jennifer, Caitlin Emma, and Jordain Carney. “House punts another funding bill as Johnson’s legislative mojo wanes.” Politico.com. November 9, 2023. https://www.politico.com/live-updates/2023/11/09/congress/another-house-gop-funding-snag-00126195.

Sloup, Tammie. “House Ag chair: Extension needed for farm bill.” FarmweekNow.com. November 7, 2023. https://www.farmweeknow.com/policy/national/house-ag-chair-extension-needed-for-farm-bill/article_f6545360-7d02-11ee-b630-237e91ed631d.html.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. “Conservation Security Program: Despite Cost Controls, Improved USDA Management is Needed to Ensure Proper Payments and Reduce Duplication with Other Programs,” Report to the Chairman, Committee on Appropriations, U.S. Senate (Senator Thad Cochran (R-MS)), GAO-06-312, April 2006, available, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-06-312.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.