Reference Prices and the CBO Gamble; Some Additional Context

James Madison memorably called factions the “mortal disease” of self-government, and with Alexander Hamilton extolled the virtues of the Constitution as a remedy to or “safeguard” against faction (Hamilton, The Federalist No. 9; Madison, The Federalist No. 10; farmdoc daily, November 11, 2022; January 5, 2023). The events of the last few weeks in the House of Representatives provide ample justification for concern, as well as to question such claims (Karni, October 25, 2023; Broadwater, October 23, 2023; Lerer and Bender, October 23, 2023; Cottle, October 23, 2023). Domestic faction is wreaking havoc on the American system of self-government beginning with, but not limited to, the United States Congress. After removing the Speaker and spending a tumultuous three weeks defeating multiple candidates, the Republican majority caucus finally elected a Speaker of the House on Wednesday, October 25, 2023 (see e.g., Edmondson, October 25, 2023; Sotomayor et al., October 25, 2023; Tully-McManus, October 25, 2023; Blake, October 24, 2023; Hulse, October 25, 2023; Ferris et al., October 24, 2023; McGraw and Isenstadt, October 24, 2023). Making sense of it all is exhausting, frustrating, and seems increasingly futile, which may be part of the point. One thing is certain: to the extent that the lesson from this episode for factions is that taking hostages in the political process is a successful tactic to achieve what may be unachievable otherwise, we will see more of it going forward.

It now remains to be seen if the newly elected Speaker, Representative Mike Johnson (R-LA), will be able to negotiate the internal factional challenges exposed during this episode, as well as the differences between that faction, the rest of the House, the Senate, and the President. Most immediately on the agenda are funding the federal government, as well as the President’s request for military and other aid to Israel, Ukraine, and the southern border. Also somewhere on the agenda, of course, is reauthorizing a farm bill; the legislative calendar for doing so in 2023 is now all but closed, however.

Farm bill reauthorization has made little actual progress and remains at an impasse, a situation not helped by the turmoil over the House Speakership. Here again the problems of faction afflict the development of public policy. Recent reporting divulged some details about a potential proposal by the House Agriculture Committee that would cut as much as $50 billion from conservation, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and Rural Development to offset the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections for the costs of increasing reference prices (Downs and Hill, October 23, 2023; Abbott, October 22, 2023). Such a proposal effectively pits farmers against farmers, and farm interests against the other interests in the farm bill coalition; this is not a recipe for success. To the extent the reporting is an accurate depiction of the preferred direction for the House Agriculture Committee, it likely represents a dead-end path for farm bill reauthorization. Reducing the assistance to low-income households, rural communities, and for conservation efforts by farmers would be extremely difficult politically; to cut those programs to increase potential payments to farmers magnifies the difficulties exponentially. Potentially more problematic, the use of the funds to offset an increase in farm program price triggers presents more of a gamble than may be commonly understood and this article seeks to add further context.

Historical Background

The reference prices in the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) program can trigger payments to those farmers who enroll base acres in the program, but only if marketing year average prices fall below the reference price trigger. That specific policy design recently turned 50-years-old, dating to August 10, 1973 and the Agriculture and Consumer Protection Act of 1973 (P.L. 93-86). In 1973, target prices represented a new direction in federal farm policy by prioritizing price-based direct payments over price-supporting nonrecourse loans. Of additional historical note, the 1973 Farm Bill was the first to formally incorporate the food stamp program (Coppess, 2018). This created an extraordinarily powerful political coalition and one that has served farm bills well for most of the ensuing five decades.

August 1973 was a notable point in history. A year earlier, the Nixon Administration, working through Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz, negotiated an historic and controversial deal with the drought-stricken Soviet Union. Using Commodity Credit Corporation authorities and funds, USDA lent the Soviet Union money to purchase surplus supplies of wheat and other American commodities (surplus supplies previously purchased with federal funds pursuant to farm support policy). Subsequently, an El Nino weather event off the coast of Peru in the winter (1972-73) decimated the anchovy harvest and caused a worldwide run on soybeans, to which the Nixon Administration reacted with a temporary embargo on soybean exports that ended in October 1973 (see e.g., farmdoc daily, May 30, 2019; July 11, 2019). Crop prices spiked but also fueled concerns about inflation, especially for consumers in grocery store aisles. For the 1973 Farm Bill debate, Secretary Butz declared that farmers had reached the “promised land” and that export markets were the answer to the farm problem (Coppess, 2018, at 140). He argued for farmers to get big or get out of farming, and to plant fencerow to fencerow. His goal, and the explicit policy of target prices in 1973, was to incentivize expansion of American production. Farmers would borrow heavily to chase the Secretary’s promised land, bringing more than 50 million acres into (or returning to) production, recreating massive soil erosion problems, and subsequently falling into an economic crisis second only to the Great Depression (see e.g., Rosenberg, 2017; farmdoc daily, May 30, 2019; July 11, 2019; February 27, 2020; April 9, 2020).

The 1973 Farm Bill was written amidst troubled political times that included the ongoing Vietnam War and the domestic protests against it. President Nixon was resoundingly re-elected in November 1972, just weeks after Congress overrode his veto of the Clean Water Act. (see e.g., farmdoc daily, April 22, 2022; October 13, 2022). Soon after the 1973 Farm Bill was enacted, on October 6, 1973, Egypt and Syria attacked Israel (State Department). The oil producing nations in OPEC retaliated against the United States for supplying weapons to Israel by imposing an oil embargo which caused gas shortages and fed an energy crises in the U.S. (State Department; Federal Reserve History). Dependent on oil for everything from tractors to fertilizers and chemicals, the energy crisis hit farmers hard. One year after the 1973 Farm Bill, President Nixon resigned in disgrace over the Watergate scandal. A month prior to resigning, President Nixon signed the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 into law (P.L. 93-344). Sometimes history’s recycling produces echoes that sound like alarms.

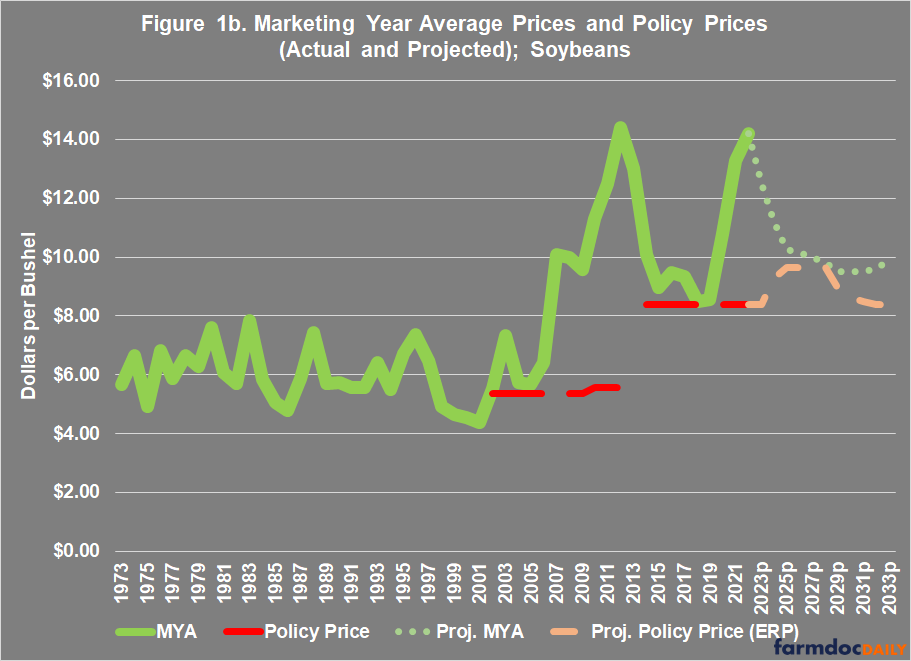

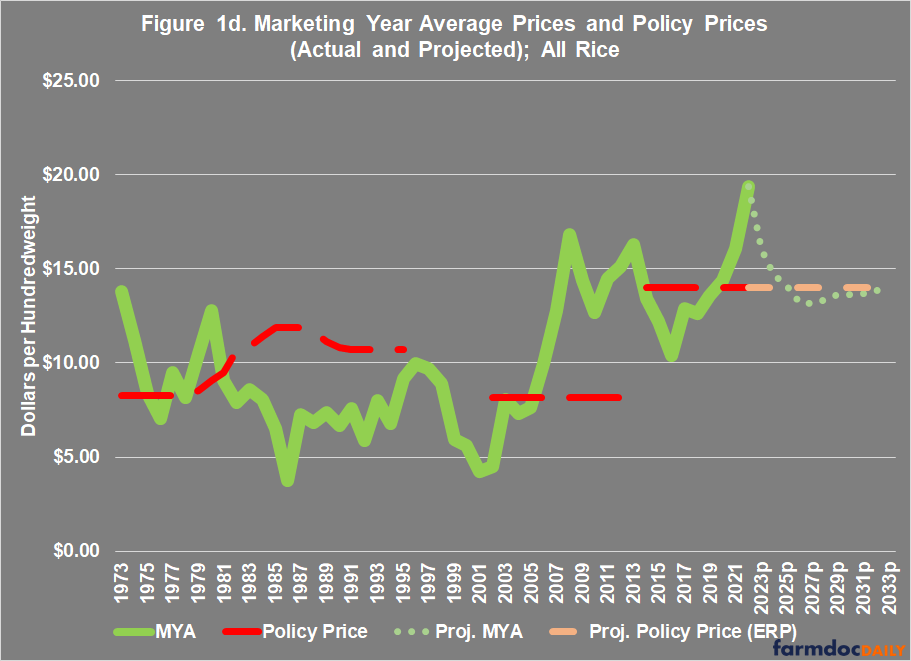

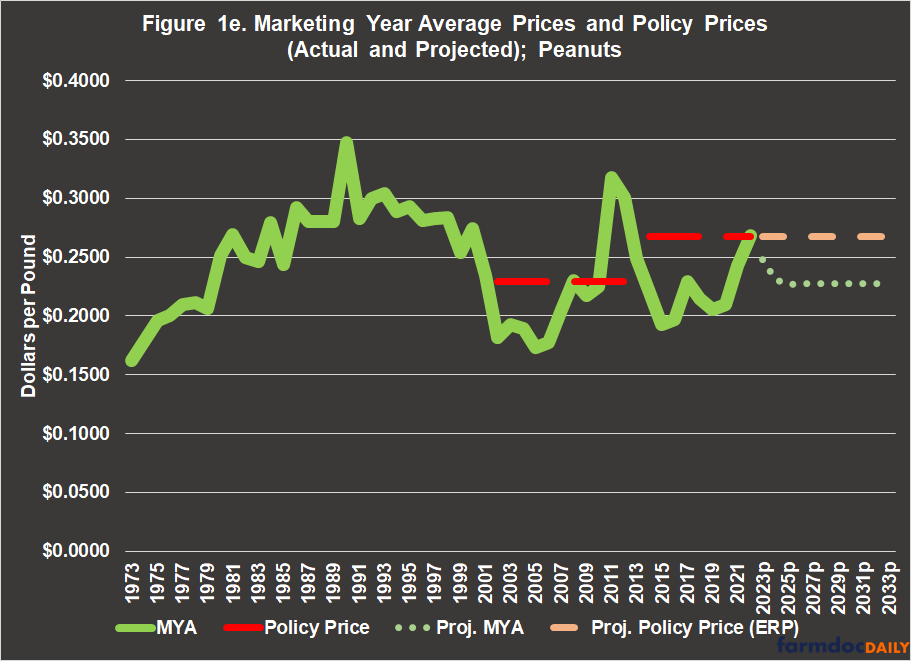

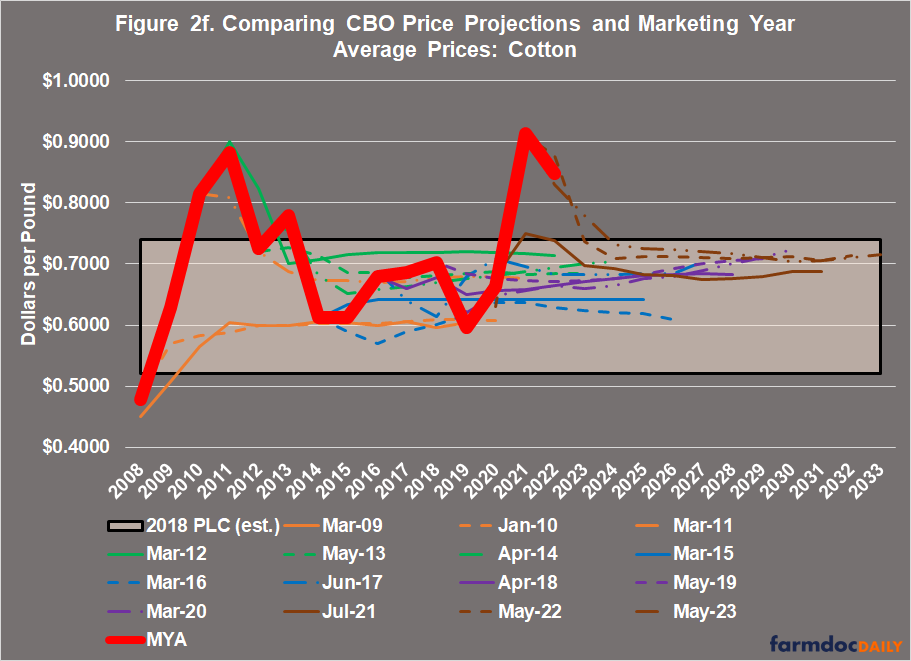

To anchor history to crop prices and farm policy, the following set of figures illustrate the marketing year average (MYA) prices for the six major program crops (corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, rice, and peanuts) since 1973. The figures include the policy prices as well: target prices (1973-1995); effective target prices (less direct payment rates, 2002-2013); reference prices (2014-2018); and the effective reference prices (2019 through projections to 2033). The figures also include the Congressional Budget Office projections through 2033. The projections are a further reminder that under the 2018 effective reference price calculation, the price trigger will increase for 90% of all base acres in the program as a result of the recent years of high crop (MYA) prices (farmdoc daily, October 5, 2023). Note an issue with cotton policy prices in Figure 1f: because Congress created “seed cotton” as a program commodity in 2018, it does not align with actual and historical cotton crop prices (seed cotton is not an actual crop). As a result, Figure 1f presents the MYA for upland cotton and estimates an effective reference price based on the seed cotton reference price created in 2018.

Figure 1. Marketing Year Average Prices and Policy Prices (Actual and Estimated Projected)

Discussion: Towards an Understanding of the CBO Gamble

The reported House Agriculture Committee proposal, if true, exposes much about the impasse. It provides the first indication of the potential costs of raising reference prices in terms of a CBO score or cost projection. Based on the proposed reductions in conservation, SNAP, and rural development to be used as offsets, the cost for reference prices would be in the neighborhood of $50 billion over 10 years. It is worth noting that the entire 10-year baseline for Title I is nearly $66 billion with almost $33 billion for PLC (FY2024 to FY2033). As noted above, the politics of doing so are perilous at best; consider that efforts to cut SNAP nearly derailed both the 2014 and 2018 Farm Bills, with each suffering an initial defeat on the House floor. The reported proposal, if pursued, would be worse than either of those previous fights. It would pit farmers against rural communities and against low-income Americans seeking help to buy food. The proposal would also pit farmers against farmers; specifically, those farmers seeking conservation funding against those who might receive additional farm program payments (see e.g., farmdoc daily, September 14, 2023; September 28, 2023).

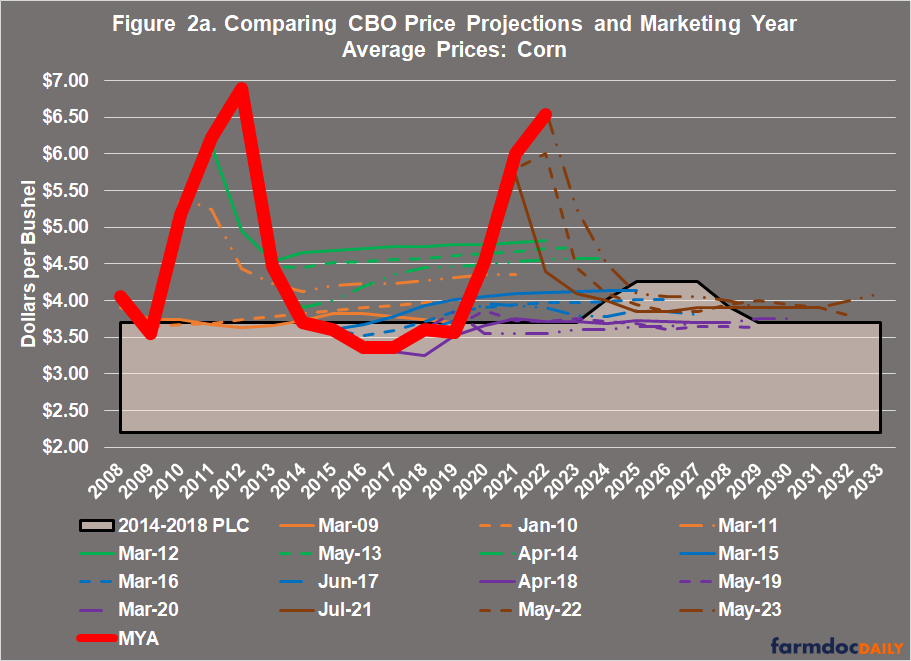

The CBO gamble exacerbates the matter further. Figures 2a through 2f attempt to represent the CBO gamble. For each of the major program crops, the figures illustrate the actual MYA prices from 2008 to 2022 (red line). Additionally, each ten-year CBO price projection for the crop is also illustrated by the various other lines. Each of these lines represent a different ten-year price projection, fifteen projections in total covering 2008 (March 2009 CBO baseline) through 2033 (from the May 2023 CBO baseline). Finally, the PLC price triggers are added with the statutory reference prices projected back to 2008 (although first enacted for 2014) for illustrative purposes, and with the effective reference prices from the 2018 Farm Bill and projected through 2033. As before, cotton uses an estimated PLC price trigger based on the 2018 reference price for seed cotton, which was not reported or projected prior to 2018.

To begin, the figures for corn and soybeans provide useful reminders about the value of the effective reference price calculation added to PLC in the 2018 Farm Bill, especially in terms of the rules for CBO scoring. Recall that CBO is required by law to produce cost estimates over 10 years, assuming continuation of the policy after it is scheduled to expire. The effective reference price provides a temporary increase in the payment trigger after multiple years of high crop prices. This can help farmers better adjust to the inevitable price declines, while avoiding large spending projections in the outyears after the policy is scheduled for reauthorization. Reducing the projected costs in the years after a farm bill expires is particularly important given the large amount of program acres for these two crops.

Figure 2. Comparing CBO Price Projections and Marketing Year Average Prices

To be clear, these figures are not a criticism of CBO projections; all projections, no matter how good, are likely to be wrong, especially for ten years into the unknowable future. This is why it is a gamble. CBO scores a program revision against its current price projections, but payments depend on the actual MYA and there is a strong likelihood that the MYA could be above the trigger price in multiple years. In those situations and years, the funds that had been used for an offset at enactment are simply lost. They cannot be recovered or reclaimed, they were spent at the time the bet was made (i.e., when used as an offset to pay for changes in the statutory provisions). The extent of the gamble is most clear for corn and soybeans in terms of the number of years in which the MYA was above the projections and the PLC price that triggers a payment. Even for peanuts, where the bet is much closer to a sure thing, there are instances in which the MYA was significantly higher than any of the projections. For all crops, the gamble is also clear in the last few years when MYA exceeded all previous projections.

Concluding Thoughts

As the recent contretemps over the House Speakership have painfully demonstrated anew, factions are destructive to a system of self-government and to policy in the public’s interest. Factions, as Madison explained, are “united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community” (Madison, The Federalist No. 10). Madison’s design was built on a pluralist competition by a large variety of interests, with coalition-building to achieve legislative outcomes that were expected to produce the best approximation of the public’s interest. The farm bill coalition provides a valuable example, but also clear warnings. This system of self-government depends on disagreement, which leads to negotiation and compromise, resolved by voting in a legislative process. Factions consider disagreement as discord, maybe disloyalty. Rather than negotiate and compromise, factions are likely to demand outcomes to suit their narrow self-interests, expect fealty, and take hostages for leverage or to force surrender or appeasement. That has been the experience in the House for the previous two farm bill reauthorizations, as well as this most recent fight over the Speakership. The outlook is foreboding.

After the events of the last month, and the ongoing impasse over farm policy, the legislative calendar is effectively closed to farm bill reauthorization in 2023. It is unlikely either committee proceeds to a markup of legislation, but it remains possible. As such, Congress will need to extend current farm program authorities to avoid the myriad problems with expiration and reversion to the 1949 Act provisions. Most other farm bill authorities, including those for operating SNAP, will either also be extended or covered by whatever legislation funds the federal government. Notably, only conservation and crop insurance do not need an extension because crop insurance is permanent law and conservation authorities were extended to fiscal year 2031 by the Inflation Reduction Act. If recent reports are accurate that the House Agriculture Committee is considering a controversial proposal to reduce conservation, SNAP, and rural development funding by $50 billion to offset the projected costs of increasing reference prices, an extension is likely the least bad option. It may even be worth considering a continuation of the current farm program authorities for another five years rather than gamble away the farm bill coalition.

This article has sought to add context to the debate by reviewing historic prices and, especially, by illustrating the gamble inherent in providing offsets for CBO scores built on 10-year crop price projections. Consider that using rural development and SNAP funding pits farm interests against key constituencies in the coalition which weakens the long-running, successful coalition and jeopardizes the entire effort going forward. Reducing conservation funding pits farmers against each other because those funds are available to all and are highly likely to be paid to farmers. Demand by farmers for conservation assistance currently outstrips funding by at least two-to-one. Moreover, the public funds are used to invest in the land and natural resources, delivering benefits for the aggregate interests of the public by reducing soil erosion, improving water quality and more. This seems like an awful lot to gamble on whether Congress can pick the right prices to write into the statute or do a better job than the current effective reference price provision that will do exactly that for most.

References

Blake, Aaron. “Tom Emmer quickly ran into a Trump-sized problem with his speaker bid.” The Washington Post. October 24, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/10/24/tom-emmer-quickly-runs-into-trump-sized-problem-with-his-speaker-bid/.

Broadwater, Luke. “’5 Families and Factions Within Factions: Why the House G.O.P. Can’t Unite.” The New York Times. October 23, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/23/us/politics/house-republicans-divisions-speaker.html.

Coppess, Jonathan. The Fault Lines of Farm Policy: A Legislative and Political History of the Farm Bill (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018).

Coppess, J. "Farm Bill 2023: Don’t Look Now, but Reference Prices Will Increase." farmdoc daily (13):182, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, October 5, 2023.

Coppess, J. "Considering Congress, Part 3: A “Republican Remedy” to the Mortal Disease." farmdoc daily (13):2, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, January 5, 2023.

Coppess, J. "The Supreme Court Returns to Troubled Waters, Part 1: A Congressional Perspective." farmdoc daily (12):156, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, October 13, 2022.

Coppess, J. "Commemorating Earth Day with a Little Legislative History." farmdoc daily (12):55, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 22, 2022.

Coppess, J. "Considering Congress, Part 2: The Mortal Disease of Self-Government." farmdoc daily (12):170, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, November 11, 2022.

Coppess, J. "The Conservation Question, Part 8: Interregnum and Acres." farmdoc daily (10):36, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, February 27, 2020.

Coppess, J. "A Brief Review of the Consequential Seventies." farmdoc daily (9):99, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 30, 2019.

Coppess, J. and K. Swanson. "The Other Side of the Seventies." farmdoc daily (9):127, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 11, 2019.

Coppess, J., N. Paulson, G. Schnitkey, C. Zulauf and K. Swanson. "Acres & Crisis: Prospective Plantings and Perspectives from the Past." farmdoc daily (10):66, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 9, 2020.

Cottle, Michell. “The People Who Broke the House.” The New York Times, October 23, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/23/opinion/house-speaker-republicans.html.

Edmondson, Catie. “House Elects Mike Johnson as Speaker, Embracing a Hard-Right Conservative.” The New York Times, October 25, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/25/us/politics/house-republicans-speaker-vote-johnson.html.

Ferris, Sarah, Jordain Carney, Olivia Beavers, Anthony Adragna, and Jennifer Scholtes. “’Are we screwed?: Anguished House GOP turns to fourth speaker pick.” Politico.com. October 24, 2023. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/10/24/house-gop-seeks-fourth-speaker-pick-00123377

Hulse, Carl. “Next Speaker Vote Is Expected in Hours in a Leaderless House.” The New York Times. October 25, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/25/us/politics/house-republicans-speaker.html.

Hulse, Carl. “The Far Right Gets Its Man of the House.” The New York Times. October 25, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/25/us/politics/mike-johnson-republican-house-speaker.html.

Karni, Annie. “In Johnson, House Republicans Elevate One of Their Staunchest Conservatives.” The New York Times. October 25, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/25/us/politics/mike-johnson-house-speaker.html.

Lerer, Lisa and Michael C. Bender. “Republicans Grapple With Being Speakerless, but Effectively Leaderless, Too.” The New York Times. October 23, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/23/us/politics/republicans-speaker-2024-elections.html.

McGraw, Meridith and Alex Isenstadt. “’I killed him’: How Trump torpedoed Tom Emmer’s speaker bid.” Politico.com. October 24, 2023. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/10/24/i-killed-him-how-trump-torpedoed-tom-emmers-speaker-bid-00123329.

Rosenberg, Nathan A., and Bryce Wilson Stucki. “The Butz Stops Here: Why the Food Movement Needs to Rethink Agricultural History.” J. Food L. & Pol'y 13 (2017): 12.

Sotomayor, Marianna, Amy B. Wang, Jacqueline Alemany, and Theodoric Meyer. “New House speaker Mike Johnson faces herculean task of uniting Republicans.” The Washington Post. October 25, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/10/25/house-speaker-mike-johnson/.

Tully-McManus, Katherine. “Mike Johnson is the GOP’s next speaker.” Politico.com. October 25, 2023.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.