The Farm Bill in Reconciliation: Loophole as Rosetta Stone; Review and Comment

Discovered in Egypt in July 1799, the Rosetta Stone is an ancient stone fragment that contains the same written text in three languages (Demotic, hieroglyphic, and Greek); with translations to Greek, the stone permitted researchers to decode or decipher ancient languages (The British Museum, July 14, 2017; Scalf, arce.org). Rosetta Stone is also a useful metaphor for any effort to decode and translate. As of July 4, 2025, budget reconciliation, bearing the sycophantic tongue-twisting title “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBA), is Public Law (P.L. 119-21). Among its many provisions are revisions to the major mandatory programs of the Farm Bill, reauthorizing them through 2031. Rushed through Congress under special budget procedures and a dearth of deliberation, much about this new federal law remains confusing and dismaying. This article reviews an expanded loophole for farm program payment limitations as a potential Rosetta Stone.

Background

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the changes enacted into law by the reconciliation bill will reduce total revenues by -$4.485 trillion in the next 10 federal fiscal years (FY2025 to FY2034), while also reducing outlays (spending) by -$1.123 trillion for a net increase in the federal debt of $3.363 trillion (CBO, June 29, 2025; CBO, July 1, 2025). The Farm Bill portion of reconciliation is projected to reduce outlays for food assistance in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) by -$195 billion, while increasing assistance to farmers by over $66 billion through multiple programs from ARC/PLC subsidies to subsidized crop insurance. CBO projected a net decrease in mandatory Farm Bill spending totaling -$120.25 billion (FY 2025 to FY 2034).

Large budget numbers approach absurdity: nearly meaningless to many, the totals obscure much about the policies fast-tracked into law with so little debate and consideration. Could certain seemingly minor provisions changing farm program payment limitations offer a Rosetta Stone of sorts? Specifically, three sections (10306, 10307, and 10308) revise long-standing and controversial aspects of farm policy. CBO scored the changes as costing over $1.7 billion, a small amount in the grand scheme of the overall score. Among the more obscure policies in the bill, these revisions did experience a brief burst of notoriety when Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA) threatened to amend them but backed down (Yarrow, June 30, 2025; Hill, June 29, 2025). Despite the small score and esoteric nature, these changes could ripple through American agriculture and rural communities with drastic and long-lasting consequences.

Discussion

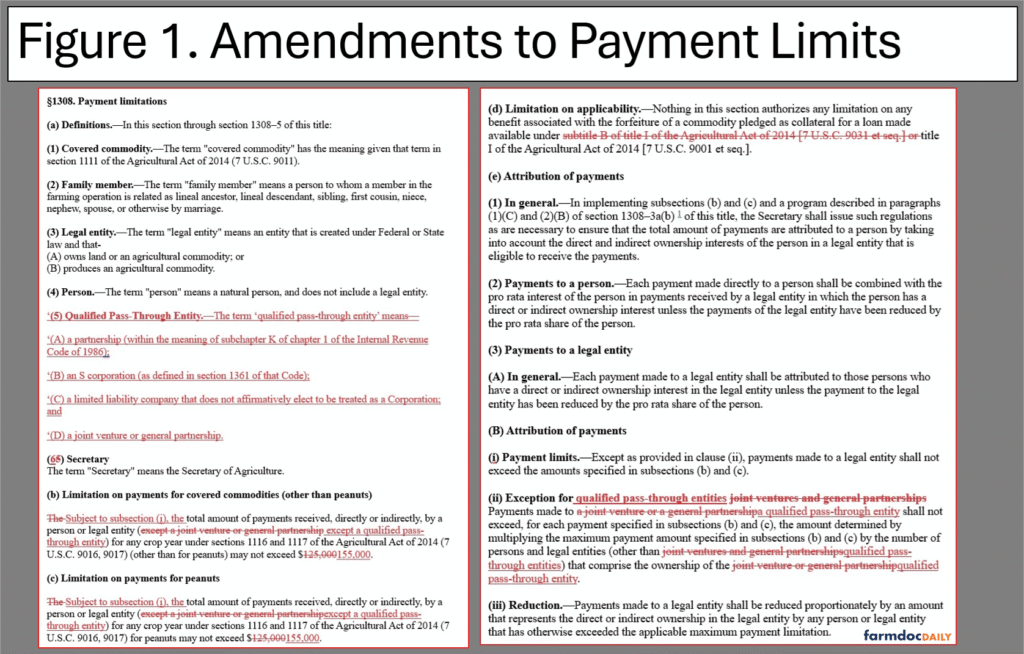

Section 10306 (“Equitable Treatment of Certain Entities”) reads as boring and benign, amending the payment limit provisions as initially enacted in the Food Security Act of 1985, which amended the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 (7 U.S.C. §1308). Payment limitations represent efforts to reform farm policy and prevent the consequences of concentrating federal money in the accounts of large, consolidated farm operations. The primary changes: (1) increase the payment limit from $125,000 to $155,000 (including the separate limit for peanut base acres); (2) require USDA to increase the payment limit each year based on inflation; and (3) expanding the exception, or loophole, that had applied to joint ventures and general partnerships.

Figure 1 illustrates the changes (redline text). In short, farms organized as joint ventures or general partnerships have been allowed to receive payments up to “the amount determined by multiplying the maximum payment amount,” or payment limit (now $155,000), by the number of persons or legal entities that comprise the ownership, attributed through no more than four layers of legal entities (7 U.S.C. §1308(e)(B)(ii)). The reconciliation text strikes “other than joint ventures and general partnerships” and replaces it with “qualified pass-through entities,” defined as: a partnership, an S corporation, a limited liability company (LLC), and a joint venture or general partnership.

The crux of the text is an expanded loophole for multiplying payment limitations to include legal fictional entities that provide liability shields to the owners (e.g., S. corporations and LLC’s). To be clear, there may well be legitimate business reasons for a farm to form as an LLC or S corporation, and many do, but that should not be conflated with this legislative loophole. Nothing previously prevented farms from doing so; what the loophole allows is the multiplication of payment limitations when so organized, thereby allowing the farm operation to maximize its haul of federal payments. This is not about farming crops or land, but rather it is about farming the federal programs and the public till.

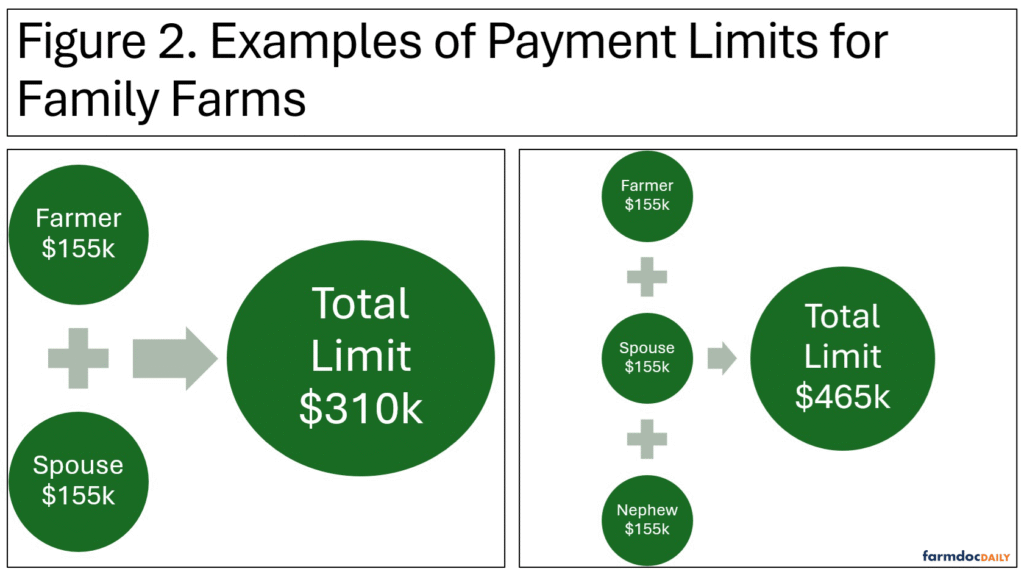

Figures 2 and 3 provide basic examples. First, Figure 2 illustrates a family farm in which the law permits the farmer a payment limit, as well as potentially one for the farmer’s spouse. It also includes the change from the 2018 Farm Bill in which other extended family members (e.g., a nephew) can be added to the operation and increase the overall payment limitations for the farm.

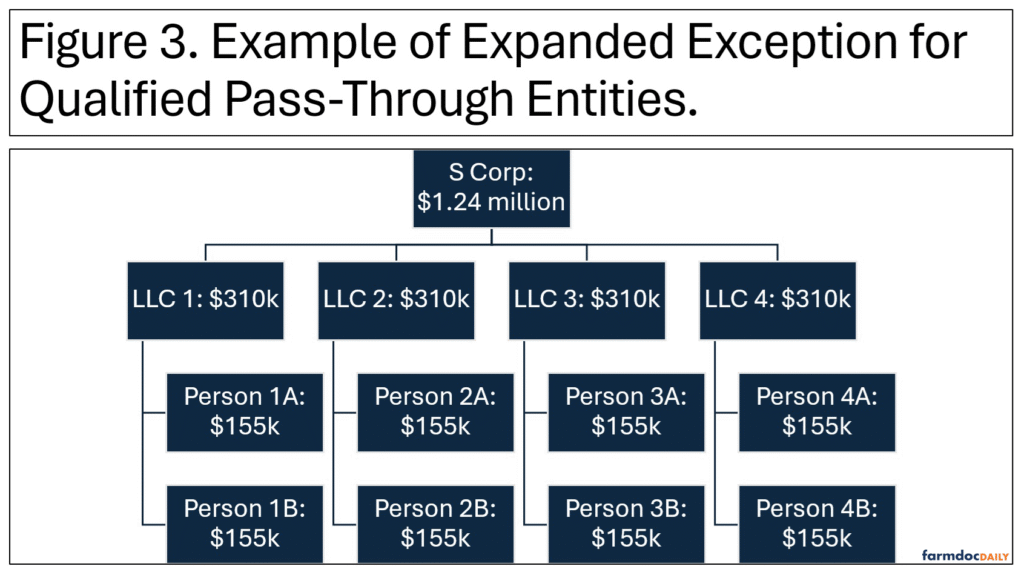

The expanded loophole is, by definition, not about family farms; it is about allowing additional payments to legal fictional entities that operate as farms. The loophole that existed for joint ventures and general partnerships now applies to all qualified pass-through entities (QPTE), as defined. Figure 3 provides an example simplified for illustration purposes. With three layers of legal entities, this example demonstrates how the exception would easily permit a farm operation to achieve an overall payment limit of $1.24 million each year. Note that each of the individual persons could also take advantage of the spouse and family member provisions illustrated above. In other words, with a modicum of creative legal and accounting help, a farm entity could expand the payment limitation to $2.5 million or more.

This was accompanied by similar changes to requirements that only people actively engaged in farming can receive payments, as well as creating a loophole in the adjusted gross income eligibility requirement for operations that receive at least 75% of their income from farming, ranching or silviculture (see, 7 U.S.C. §1308-1; §1308-3a; see also, farmdoc daily, April 8, 2015; August 28, 2020; November 4, 2024). In total, the changes permit some farm operations to effectively avoid any limit on the amount of federal funds they can collect. The bigger the operation, the more incentive to take advantage of the loopholes. Taking advantage of the loopholes will, in turn, permit those farm operations to grow larger and more consolidated at taxpayer expense.

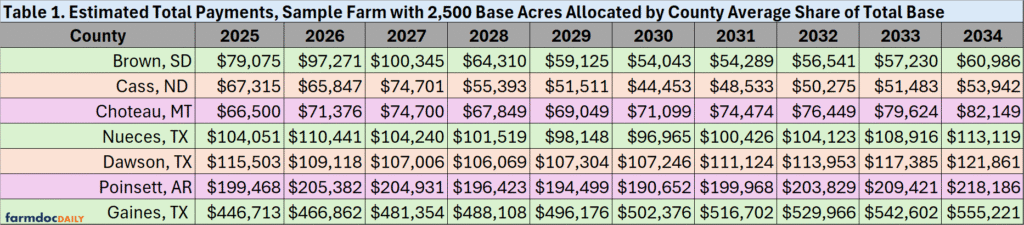

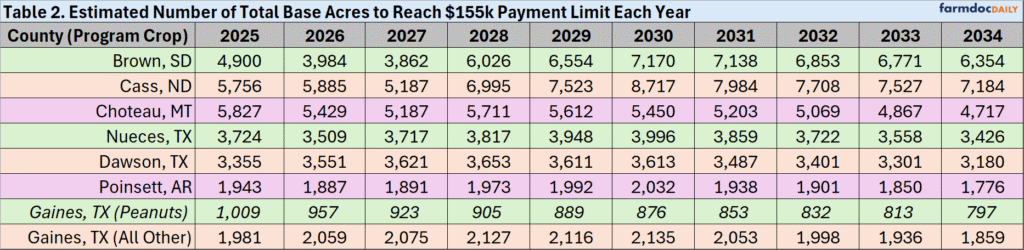

Tables 1 and 2 provide examples. Often lost (or avoided) is the fact that farmers do not farm the CBO baseline or the 10-year score, lobbyists do. Moreover, it is rare that a farmer raises only a single crop or has base acres of only one program crop, but CBO projections—and too much of the policy conversation, when there is one—operates on an individual crop-by-crop basis, siloing farm policy as a result. Both tables present this loophole issue from a sample or simulated farm perspective using six different counties, representing each of the counties with the most base acres of each of the major program crops (e.g., Brown County, South Dakota has the most corn base acres, Cass County, North Dakota the most soybean base acres, etc.). Both tables use the projections for ARC and PLC visualized in the Policy Design Lab (Policy Design Lab, “Proposal Analysis”; farmdoc daily, July 3, 2025).

Table 1 calculates expected total payments for a sample farm of 2,500 total base acres in each of the six counties: the program crop’s share of the total base acres in the county is applied to the total of 2,500 base acres and multiplied by the projected payment rates. Whether 2,500 base acres constitutes a large farm or not is beside the point, the table compares farms of the same size in different counties with base acres of different crops, highlighting the different levels of expected payments. Here the disparities in policy design are exposed in the vastly different expected payments for farms of the same size.

Table 2 provides the other side of the issue, using projected payment rates and base acres to estimate the total number of base acres it would take to hit the $155,000 individual payment limit each year. Again, the policy design disparities result in significant differences in the size of farms that would be expected to encounter the payment limit.

Providing large farm operations an easy button to avoid any limits on the amount of federal funds they can collect in a year is likely to have negative consequences, especially for other farmers. It is important to keep in mind that federal farm payments are free to the farmers with base acres, there are no requirements that the farmer suffers an actual or commensurate loss in the crop year, nor that the crop for which the payment is attributed was planted (or that any crop was planted, for that matter). In the parlance of other policies: there are no work requirements for farm program payments. Farm operations that collect large federal payments can use the funds for whatever ends it chooses, most likely to include bidding up cash rents and land prices against neighboring farmers. The bigger the farm, the more incentive to take advantage of the loopholes which, in turn, will permit those farm operations to grow larger and more consolidated at taxpayer expense. It is a stunning change to federal law, especially considering that it was paired with nearly $200 billion in cuts to food assistance for low-income households. It is likely that only speed and the special protective procedures for reconciliation could have permitted this to become law.

Concluding Thoughts and Commentary

Policy is the language of politics and power; politics is primarily a competition of power. In any competition, the rules of the game matter. This most recent reconciliation effort provides a clear and emphatic case in point. The payment limit loophole helps decode the issue and the two poles or ends to policy. On one end are the costs to the federal government measured in Congressional Budget Office baselines and scores. On the other end are the people impacted by it, those helped by the policy and those hurt by it.

On the cost end of policy, this episode is a lesson in factional political power and the vital importance of the rules of the game. The Framers of the Constitution expected the creation of federal law to be a competition amongst factional powers and designed a system intended to facilitate that competition and require negotiated outcomes in a complex process. The results of that competition were expected to produce the best approximation of the public interest (farmdoc daily, November 11, 2022; January 5, 2023; January 12, 2023). The design of Congress, however, has important asymmetries favoring smaller, more concentrated and homogeneous factions (farmdoc daily, January 26, 2025). Federal budget policy has magnified those asymmetries and drastically altered the legislative process, primarily through the singular focus on the costs of policies and ignoring the impacts.

By focusing on large baseline costs under special rules for an expedited, truncated process where public deliberation is diminished, budget policy obscures factional self-interest behavior in the design of policies, allowing them to hide problematic policy. This enhances exponentially the power of the smallest interests with the least impact on the baseline—even if the individual benefits are relatively large and generous. Against magnified power, competition falters and opposition withers; when even stalwart defenders surrender without a fight, the state of play is clear. The opposite is the case for any greater public interest: the more people a policy helps, the more it costs in the baseline—even if the individual benefits are relatively small—and the more vulnerable it is in the process. Qualified pass-through farm entities get an easy button for more federal payments, low-income individuals get more paperwork burdens and requirements or lose assistance.

Where competition is missing or too weakened, factions grab all the benefits they can. When factional power centers dictate outcomes, the result is less policy and more fiat. Arguably more incredible, budget policy can cause these harms without ever actually addressing the budget issues that are its reason for existing: reconciliation will add trillions to the national debt, failing to accomplish budgetary discipline but delivering unnecessarily bad policy to the people who pay for it. The final outcome is a bad caricature of the fears of the Framers arguably best seen from the other direction.

On the other end of policy are the people impacted by the decisions embedded in policy design. Why would federal policy favor legal fictional entities over individual family farmers? Is a qualified pass-through entity a better farmer, or does it simply receive competitive advantages that can be overwhelming, such as being able to harvest more federal payments? If such entities have fewer or lower losses, they don’t need the extra payments; if those entities suffer more or larger losses, they shouldn’t be encouraged with extra subsidies and other competitive advantages. Is this policy also a symptom of a much larger problem in society, with laws prioritizing fictional legal entities over people, providing the former with special gifts and benefits at the disadvantage of the latter?

The obscure payment limit policy provides a sharp example. A real-world implication for farmers will be that qualified pass-through entities will be able to increase federal payments. The additional federal money will most likely be used to bid up cash rents and land prices. No farmer would want this policy and, going forward, any farmer that has to pay more to rent or buy land, can thank this provision and those who helped make it happen. With higher cash rents and land costs, many farmers will be driven out of farming while qualified pass-through farm entities will increase acreage, as well as federal payments. It is a cycle that builds on itself; whether intended or not, the end result will be to accelerate consolidation in American agriculture. In the realm of the program crops, this new reality likely spells the end of whatever is left of the traditional family farmer. In short order, all farms will need to be qualified pass-through entities competing to maximize payments and base acres. Not only farmers will be hurt, however, because losing family farmers will harm rural communities as well.

In the end, thinking about the people on the other end of the policy conjures hypotheticals with scenes worthy of a movie or a verse in a Bruce Springsteen song. In some small town, a mother fights her way through a mound of paperwork hoping to get assistance to put food on the table for her kids. Meanwhile, on the street outside a farm entity manager drives by in his shiny new pickup truck. He is on his way to the lawyer to revise the qualified pass-through entity so that it can increase federal payments. Afterwards, with expectations of more federal cash, that farm entity manager visits an elderly landowner in town and proposes renting the land for a higher amount. At some point, the money talks, trumping the existing relationship with the current tenant. When those leased acres change hands, it likely leads to another family farmer going out of business. And it may be that, at some point, it is the former family farmer who is next in line to sort through paperwork for food assistance.

References

The British Museum. “Everything you ever wanted to know about the Rosetta Stone.” July 14, 2017. https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/everything-you-ever-wanted-know-about-rosetta-stone.

Congressional Budget Office. “Estimated Budgetary Effects of an Amendment in the Nature of a Substitute to H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, Relative to CBO’s January 2025 Baseline.” Cost Estimate. June 29, 2025. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61534.

Congressional Budget Office. “Information Concerning the Budgetary Effects of H.R. 1, as Passed by the Senate on July 1, 2025.” Cost Estimate. July 1, 2025. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61537.

Coppess, J. "Reviewing the USDA Proposal to Limit Farm Program Payment Eligibility." farmdoc daily (5):64, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 8, 2015. https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2015/04/reviewing-usda-proposal-to-limit-payment-eligibility.html.

Coppess, J. "Considering Congress, Part 2: The Mortal Disease of Self-Government." farmdoc daily (12):170, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, November 11, 2022. https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2022/11/considering-congress-part-2-the-mortal-disease-of-self-government.html.

Coppess, J. "Considering Congress, Part 3: A “Republican Remedy” to the Mortal Disease." farmdoc daily (13):2, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, January 5, 2023. https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2023/01/considering-congress-part-3-a-republican-remedy-to-the-mortal-disease.html.

Coppess, J. "Considering Congress, Part 4: The Double Majority." farmdoc daily (13):6, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, January 12, 2023. https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2023/01/considering-congress-part-4-the-double-majority.html.

Coppess, J. "Considering Congress, Part 5: An Initial Critique of the Design." farmdoc daily (13):15, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, January 26, 2023. https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2023/01/considering-congress-part-5-an-initial-critique-of-the-design.html.

Coppess, J., G. Schnitkey, C. Zulauf, N. Paulson and K. Swanson. "Reviewing USDA Revisions to the Payment Limitation and Eligibility Rules." farmdoc daily (10):157, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, August 28, 2020. https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2020/08/reviewing-usda-revisions-to-the-payment-limitation-and-eligibility-rules.html.

Coppess, J., G. Schnitkey, C. Zulauf and N. Paulson. "Reviewing the Latest Ad Hoc Payment Proposal in Congress." farmdoc daily (14):200, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, November 4, 2024. https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2024/11/reviewing-the-latest-ad-hoc-payment-proposal-in-congress.html.

Hill, Meredith Lee. “Senate GOP leaders may face a farm bill floor fight in megabill debate.” Politico.com. June 29, 2025. https://www.politico.com/live-updates/2025/06/29/congress/senate-republicans-megabill-farm-bill-floor-fight-00432298.

Monaco, H., J. Coppess, N. Paulson and G. Schnitkey. "Farm Bill in Reconciliation: ARC/PLC Payment Projections; Policy Design Lab Update." farmdoc daily (15):122, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 3, 2025. https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2025/07/farm-bill-in-reconciliation-arc-plc-payment-projections-policy-design-lab-update.html.

Scalf, Foy. “The Rosetta Stone: Unlocking the Ancient Egyptian Language.” American Research Center in Egypt. https://arce.org/resource/rosetta-stone-unlocking-ancient-egyptian-language/.

Yarrow, Grace. “Grassley strikes deal to table farm aid amendment.” Politico.com. June 30, 2025. https://www.politico.com/live-updates/2025/06/30/congress/grassley-strikes-deal-to-table-farm-aid-amendment-00434674.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.