Budgetary Dissonance and the 2024 House Farm Bill

Dissonance is defined as a lack of agreement, or an inconsistency; a common usage involves inconsistencies between one’s beliefs and actions (Merriam-Webster.com). Similarly, cognitive dissonance is a psychological theory that has applications in public policy and politics (see e.g., Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen, 2018; Stone and Fernandez, 2008; Akerlof and Dickens, 1982). The 2024 Farm Bill reported by the House Committee on Agriculture may have introduced a version of this concept that can be called budgetary dissonance (H.R. 8467). This article seeks to unpack this complicated issue and consider its consequences.

Background

Budgetary problems may be the most painfully esoteric, and easily one of the most confusing, matter in the 2024 House Farm Bill; budget problems could also be the most consequential, both for the Farm Bill and beyond. The issue involves the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), statutory budget provisions, House rules, and past practices in the use of, and long-standing authorities for, the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). In short, the House Agriculture Committee needed an offset for the substantial increase in spending that was projected to result from the increase in reference prices in the Farm Bill. The Committee included a provision limiting CCC authority but the CBO score for the change was not sufficient to offset the costs. Going into markup, the Committee disputed CBO’s scoring and attacked the nonpartisan, non-affiliated agency that Congress created 50 years ago to score legislation (House Agriculture Committee, CBO-CCC). There is no easy or straightforward explanation for the issue. It is, in other words, a budget issue and all that that entails.

The issue also exposes significant issues with federal budget policy as it has evolved since 1974 (see e.g., farmdoc daily, March 23, 2023; February 13, 2020; July 18, 2019; April 18, 2019; November 29, 2018). Among other things, Congress created CBO as a non-partisan, unaffiliated agency of Congress to provide objective analysis on budget and economic matters. Over time, Congress has changed budget policy to increase its disciplinary nature and operation, placing overwhelming emphasis on reducing spending. For example, Congress revised the reconciliation process in 1981 to permit requiring cuts to mandatory programs. In 1985, Congress created sequestration (automatic across-the-board cuts) to cut spending when Congress did not meet its budgetary goals. In 1990, Congress created Pay-as-You-Go (PAYGO) rules that require any projected increases in spending be offset by decreases in spending elsewhere (or be paired with revenue increases). Along the way, Congress required CBO to project 10-year spending estimates to create a baseline against which changes were measured, as well as requiring CBO to score legislative changes against the baseline over one-, five-, and ten-year budget windows regardless of the length of the authorization (CBO, April 18, 2023; 2 U.S.C. §907; CBO, April 18, 2023).

As it has increased the disciplinary nature of budget policy, Congress has put increasing demands on CBO, as well as the baseline and scoring process. Arguably, these developments have warped the legislative process and altered policymaking in numerous fundamental ways. The budget has further complicated achieving legislation, rendering it more difficult and complex. Budget discipline has stifled innovation, evolution, and development of policy. These outcomes were, however, largely a feature, not a bug; they appear to have been ideological and intentional, with predictable and expected consequences (see e.g., Coppess, 2024; Wildavsky, 1988; farmdoc daily, February 29, 2024). In other words, the budget problems facing the House Farm Bill are self-inflicted problems of Congress’ own making and a form of dissonance. The problems are the direct result of a long effort by Congress to force itself to reduce spending, while also being unwilling to live by its own rules. As an example, the 118th Congress tightened the offset requirements further, with a provision known as “CUTGO” which prohibits consideration of any legislation that increases mandatory spending within either a six-year or 11-year window (House, January 10, 2023, Rule XXI, clause 10; Heniff, CRS, May 9, 2023).

Discussion

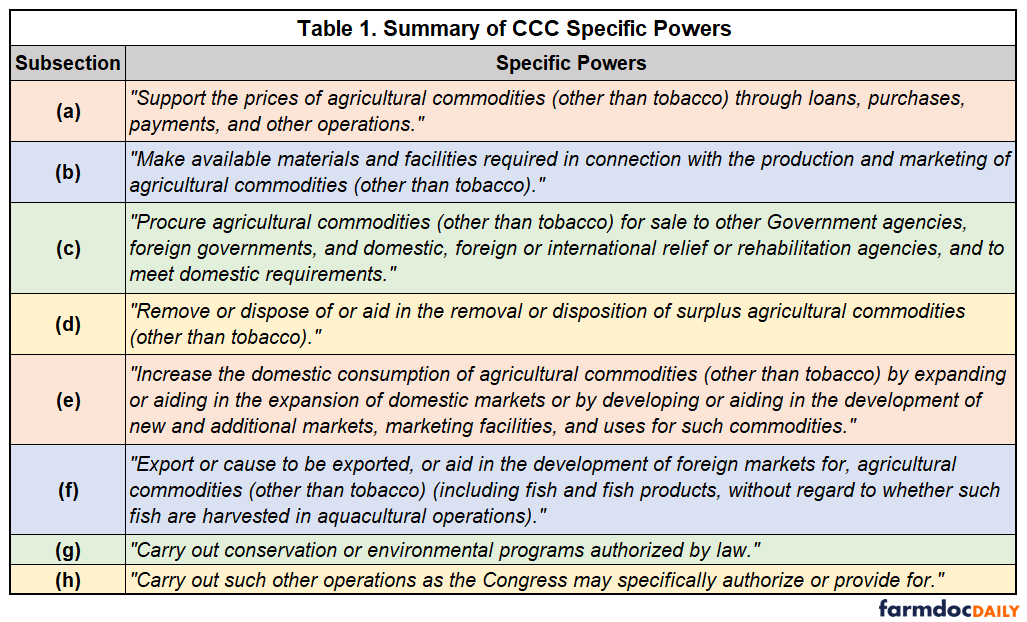

Section 1608 of the House Farm Bill seeks to limit Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) authorities available to the Secretary of Agriculture. Specifically, the legislative text provides that “[n]otwithstanding section 5 of the Commodity Credit Corporation Charter Act (15 U.S.C. 714c), during fiscal years 2025 through 2034, the Commodity Credit Corporation is authorized to use its general powers only to carry out operations as the Congress may specifically authorize or provide for” (H.R. 8467). Among the materials it released for the markup, the House Agriculture Committee included a document claiming “inaccuracies” in how the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected the reductions in spending (or outlays) projected to result from this provision. Specifically, the committee disputes CBO’s estimate that the text would save $8 billion. The Committee argued that the recent usage of CCC demonstrated that “CBO has mis-forecast outlays under Section 5 by more than $60 billion since 2018” (House Agriculture Committee, CBO-CCC). Notably, the May 2023 CBO baseline against which the House Farm Bill is expected to be scored included $10 billion in CCC Charter Act outlays and the February 2024 update increased that outlay projection to $15 billion in the 10-year window (CBO, Details About Baseline Projections for Selected Programs).

The CCC was first created by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933 to provide a funding mechanism for New Deal farm relief efforts (Stubbs, CRS, January 14, 2021). Fifteen years later, Congress authorized broad, flexible powers to the Secretary of Agriculture when it enacted the CCC Charter Act of 1948 (15 U.S.C. §714; P.L. 80-806, available from the National Agricultural Law Center, CCC Charter Act; compilation available from the Senate Agriculture Committee, CCC Charter Act). There are two key provisions in the CCC Charter Act that are relevant to the House Farm Bill scoring issue. First, the general powers section (section 4) authorizes the CCC (operating through USDA) to directly borrow up to $30 billion directly from the U.S. Treasury and includes authority to transfer funds to other agencies (15 U.S.C. §714b). Second, the specific powers section (section 5) of the CCC Charter Act authorizes specific categories of use of the general powers and the funds borrowed to assist farmers (15 U.S.C. §714c). There are eight specific powers listed in the statute, as quoted in Table 1.

Critical to this matter was the Trump Administration’s unique use of the CCC authorities and funding. In 2018, and then again in 2019, USDA created the Market Facilitation Program (MFP) without Congressional authority. In its final rule, USDA claimed it was using a combination of the CCC specific powers for assisting in “the disposition of surplus commodities” (subsection (d)) and “to increase the domestic consumption of agricultural commodities” by expanding, aiding or assisting the development of new markets (subsection (e)) (7 CFR Part 1409, Final Rule). Using this authority, USDA provided $8.6 billion in direct payments to some producers in 2018 and $14.5 billion in 2019 (see, farmers.gov/mfp; see also, GAO-20-700R; GAO-22-104259; GAO-22-468). Little known, USDA also made an unprecedented transfer of $20 billion from the CCC to the Office of the Secretary in August 2019. The timing was key because the federal fiscal year ends on September 30th and CCC funding is necessary beginning October 1 (the new fiscal year) to make farm program payments and marketing loans. Doing so created what is known as a budget anomaly that effectively forces appropriators to replenish the CCC accounts and restore the $30 billion borrowing limit or risk operations for authorized programs (see, CRS Insight, September 17 2019). For the painfully curious, the transfer was reported by USDA to Congressional appropriators and was the only significant transfer from CCC to the Office of the Secretary reported in recent years, although just over $1 billion was reported as transferred the following year (USDA-OBPA, 2022 Explanatory Notes, CCC; USDA-OBPA, Congressional Justifications). The Continuing Resolution for FY2020 contained the necessary reimbursement for CCC accounts (P.L. 116-59, Section 119).

Much of this unusual operation of the CCC was lost to the momentous events of 2020, from the covid pandemic to the presidential election. As part of the response to the pandemic, USDA created the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP) that combined emergency funding appropriated by Congress ($9.5 billion) to the Office of the Secretary with CCC funds ($14 billion) that were the result of a replenishment of the CCC account but were not available until June 2020 (CFAP1, Rule). In September 2020, USDA created a second CFAP program with an estimated $13.2 billion in CCC funds and based on the specific powers in section 5(b), (d), and (e) of the CCC Charter Act (CFAP2, Rule). USDA has reported spending $11.8 billion in CFAP1 and $19.5 billion in CFAP2 (see, farmers.gov, CFAP1 Dashboard; CFAP2 Dashboard). More recently, $3.5 billion of CCC funds were used to create the Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities (see, USDA-OBPA, 2024 USDA Budget Explanatory Notes, CCC; USDA, Partnership for Climate-Smart Commodities).

Without a doubt, the six years since Congress last reauthorized the Farm Bill (2018) have witnessed anomalous uses of the CCC authorities and funds. This is presumably why CBO has begun including CCC Charter Act outlay projections in its baselines. Since 2020, the CCC funds have also been intermingled with ad hoc and emergency supplemental appropriations, complicating the picture significantly. Discretionary decisions by USDA have not traditionally been included in the baseline, nor have they been scored against the agricultural committees or the Farm Bill. CBO generally does not include appropriations in baseline projections, which means appropriations are not available as offsets for mandatory program spending. Importantly, authorizing committees have no control over future appropriations bills, especially ad hoc and emergency appropriations. In other words, there isn’t much for CBO to work with in terms of the standard operating procedures for federal budget policy.

For this situation, little clarity can be found in budget rules and procedures designed to limit federal spending. Any offset likely requires projecting into the future the anomalous discretionary decisions by USDA, as well as some incorporation of ad hoc, emergency, or supplemental appropriations. The cost of the House Farm Bill’s reference prices has brought this situation to a head and places great weight on the words the committee used in its legislative text. Section 1608 regurgitates subsection (h) of Section 5 in circular fashion but does not address specific uses or the transfer of funds to the Office of the Secretary (compare, H.R. 8467; 15 U.S.C. §714c; 15 U.S.C §714b and §714f). The text also uses a “notwithstanding” clause which could operate as limiting or not (see e.g., Killion, CRS, May 19, 2022; NLRB v. SW Gen., Inc., 580 U.S. 288, 302 (2017) (“A ‘notwithstanding’ clause . . . just shows which of two or more provisions prevails in the event of a conflict”)). The provision could provide no actual limit on the use or transfer of CCC funds (e.g., Congress has specifically authorized operations and acquiesced in previous uses; each appropriation that replenishes the CCC accounts may provide for any and all operations), or it completely eviscerates any use of CCC funds unless Congress explicitly authorizes the specific operation(s) in advance. The latter interpretation could have substantial unintended consequences. For comparison, the general powers (Section 4) includes a limiting phrase for entering contracts, limiting the authority to a fixed amount “unless . . . provided in advance in appropriation Acts” (7 U.S.C. §714b). Additionally, beginning in 2012, Appropriators limited USDA authority to use CCC by explicitly preventing the use of funds for “surplus removal activities or price support activities under Section 5” of the CCC Charter Act, a limitation that was continued through FY2017 (P.L. 112-55; P.L. 113-6; P.L. 113-76; P.L. 113-235; P.L. 114-113; P.L. 115-31). Ultimately, the actual operation of the provision depends on interpretations of the text by USDA and by the courts, should a lawsuit proceed from the interpretation. Scoring this provision appears challenging in the extreme.

Concluding Thoughts

About the only thing clear in the obscure and esoteric scoring problem for the House Farm Bill is the budgetary dissonance. In seeking a score for an offset that is not supported by the scoring agency Congress created, the House Farm Bill collides with budget rules and procedures Congress has put in place, including the stricter version of those rules by the 118th Congress. What makes this dissonance particularly notable is that it is in service of an attempt to offset the enormous increase in costs of farm program payments that would result largely from the decision to drastically increase statutory reference prices. Importantly, this clashes with how the House Farm Bill addresses other mandatory funding costs. While the House Farm Bill increases budget authority, or funds available, for conservation programs, it offsets those increases by rescinding the additional funds appropriated in the Inflation Reduction Act. This may produce additional consequences for conservation assistance, but analysis awaits a formal CBO score. Finally, and most controversially, the House Farm Bill reduces spending in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) as an offset to a variety of other spending increases. The provision is in Title 12, the miscellaneous title (Sec. 12401, H.R 8764) and limits the Secretary’s authority to adjust the Thrifty Food Plan beginning in FY2027. As with conservation, further analysis of the impacts of this change awaits a former CBO score. The disparate treatment of conservation and SNAP, as compared to farm program payments, magnifies the budgetary dissonance of the House Farm Bill. That budgetary dissonance could serve a larger purpose, however, because it exposes fundamental flaws in federal budget policy, as well as the troubling consequences of budget policy for policymaking and the legislative process. Under the guise of budget discipline, federal budget policy has damaged legislating but consistently failed to discipline federal deficits or reduce the national debt.

References

Acharya, Avidit, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen. "Explaining preferences from behavior: A cognitive dissonance approach." The Journal of Politics 80, no. 2 (2018): 400-411. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/694541.

Akerlof, George A., and William T. Dickens. "The economic consequences of cognitive dissonance." The American economic review 72, no. 3 (1982): 307-319. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1831534.

Congressional Budget Office. “CBO Describes Its Cost-Estimating Process.” Budget Primer. April 2023. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-04/59003-cost_estimate_primer.pdf.

Congressional Budget Office. “CBO Explains How It Develops the Budget Baseline.” Budget Primer. April 2023. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-04/58916.pdf.

Coppess, Jonathan. Between Soil and Society: Legislative History and Political Development of Farm Bill Conservation Policy (University of Nebraska Press, 2024). https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/nebraska/9781496225146/.

Coppess, J. "Hiding Behind the Baseline: Big Numbers and the Budget Game." farmdoc daily (14):42, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, February 29, 2024.

Coppess, J. "The Debt Ceiling: Reviewing Federal Budget Data." farmdoc daily (13):53, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, March 23, 2023.

Coppess, J. "Obligatory Annual Budget Detour." farmdoc daily (10):27, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, February 13, 2020.

Coppess, J. "The Debt Limit: A Saga of Self-Inflicted Trouble." farmdoc daily (9):131, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, July 18, 2019.

Coppess, J. "Federal Budget Discussion, Part 2: Revenues and Spending." farmdoc daily (9):70, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 18, 2019.

Coppess, J. "Federal Budget Discipline and Reform: A Review and Discussion, Part 1." farmdoc daily (8):218, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, November 29, 2018.

Heniff, Bill, Jr. “House Rule XXI, Clause 10: The CUTGO Rule.” Congressional Research Service. Updated, May 9, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/download/R/R41510/R41510.pdf/.

Killion, Victoria L. “Understanding Federal Legislation: A Section-by-Section Guide to Key Legal Considerations.” Congressional Research Service, R46484. Updated May 19, 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/download/R/R46484/R46484.pdf/.

Stone, Jeff, and Nicholas C. Fernandez. "To practice what we preach: The use of hypocrisy and cognitive dissonance to motivate behavior change." Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2, no. 2 (2008): 1024-1051. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00088.x.

Stubbs, Megan and Jim Monke. “The CCC Anomaly in an FY2020 Continuing Resolution.” Congressional Research Service, INSIGHT. September 17, 2019. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/download/IN/IN11168/IN11168.pdf/.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. “USDA Market Facilitation Program: Information on Payments for 2019.” GAO-20-700R, September 14, 2020. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-700r.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. “USDA Market Facilitation Program: Stronger Adherence to Quality Guidelines Would Improve Future Economic Analyses.” GAO-22-468. December 20, 2021. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-468.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. “USDA Market Facilitation Program: Oversight of Future Supplemental Assistance to Farmers Could Be Improved.” GAO-22-104259. February 3, 2022. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-104259.

U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Agriculture. “Inaccuracies in the Congressional Budget Office Forecast of Spending Under Authority Granted by Section 5 of the Commodity Credit Corporation Charter Act.” https://agriculture.house.gov/uploadedfiles/cbos_ccc_inaccuracies.pdf.

U.S. House of Representatives. “Rules of the House of Representatives: One Hundred Eighteenth Congress.” Prepared by Cheryl L. Johnson, Clerk of the House of Representatives. January 10, 2023. https://cha.house.gov/_cache/files/5/3/5361f9f8-24bc-4fbc-ac97-3d79fd689602/1F09ADA16E45C9E7B67F147DCF176D95.118-rules-01102023.pdf.

Wildavsky, Aaron. The New Politics of the Budgetary Process (Glenview: Scott, Foresman, 1988).

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.