History and the 2024 House Farm Bill

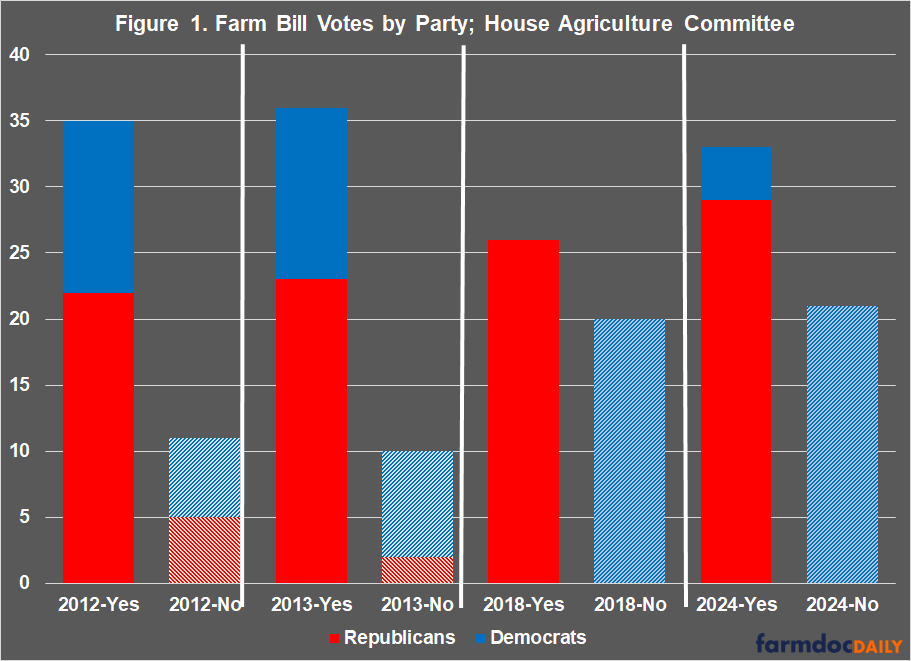

The House Agriculture Committee advanced its version of the 2024 Farm Bill reauthorization, the Farm, Food, and National Security Act of 2024, on May 24, 2024 (Farm Policy News, May 24, 2024; Wicks, Alvey, and Brasher, May 24, 2024; Yarrow and Brown, May 28, 2024). A thin veil of bipartisanship after the midnight hour—four Democrats voted with 29 Republicans to report the bill 33 to 21—provides little cover for the troubled legislation, which is unlikely to be considered on the House floor in this election year. Analysis on the specific changes to law proposed in the legislation continues, but this article steps back in search of historical and political perspective on the challenges consuming recent Farm Bill reauthorizations (see e.g., farmdoc daily, May 29, 2024; May 21, 2024).

Background

In 2007, the House Agriculture Committee reported the Farm, Nutrition, and Bioenergy Act of 2007 (H.R. 2419) by voice vote, effectively agreeing to report the bill to the House without any opposition (H. Rept. 110-256). Four days after it was reported that Farm Bill passed the House by a vote of 231 to 191 (Roll Call 756). Nearly a year later, the 2008 Farm Bill was enacted into law over President George W. Bush’s veto (P.L. 110-234).

In 2012, the Committee reported the Federal Agriculture Reform and Risk Management Act of 2012 by a vote of 35 to 11 (H.R. 6083; see also, Roll Call #20). House leadership refused to allow the 2012 version of the Farm Bill to be considered on the floor in that election year. The following year, the Committee reported the Federal Agriculture Reform and Risk Management Act of 2013 by a similar vote of 36 to 10 (H.R. 1947; see also, Roll Call #12). That Farm Bill was initially defeated on House floor by a vote of 195 to 234 (Roll Call 286) after a bitter, partisan dispute over an amendment to cut the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). SNAP was subsequently removed from the Farm Bill and both were passed separately on party-line votes before being rejoined for conference and eventually becoming the Agricultural Act of 2014 (H.R.2642; House Agriculture Committee, 2014 Farm Bill; P.L. 113-79).

In 2018, the Committee reported the Agriculture and Nutrition Act of 2018 (H.R. 2) by a vote of 26 to 20 (House Agriculture Committee, 2018 Farm Bill; House Agriculture Committee, April 18, 2018; H. Rept. 115-661). Only Republicans voted to report that bill, however, after the partisan fight over cutting SNAP consumed the Committee, along with conflicts over changes to conservation policy and eligibility standards for farm program payments. That Farm Bill reauthorization was initially defeated on the House floor by a vote of 198 to 226 (Roll Call 205). On a second try, the bill passed the House a month later, June 21, 2018, by a vote of 213 to 21 with no Democratic votes (Roll Call 284). A conference committee compromise was produced in the lame duck session after the midterm elections and the 2018 Farm Bill was enacted on December 20, 20218 (P.L. 115-334). Placing last Friday’s vote in this recent history, Figure 1 illustrates a compilation of the previous four House Agriculture Committee Farm Bill reauthorization votes.

The fate of the 2024 reported bill on the House floor remains in serious doubt given initial indications that floor time will not be scheduled prior to September. The odds that the House will consider a $1.5 trillion, controversial piece of legislation in the middle of a contentious campaign season, and with the end of the fiscal year looming, are miniscule at best. The 2024 bill marks three consecutive partisan and contentious reauthorization efforts in the House. There exists no historical precedent for this situation. The previous most contentious era for Farm Bills predated food stamps/SNAP and culminated in the first defeat of a Farm Bill on the House floor in 1962. In search of some understanding about the current state of reauthorization, the following discussion summarizes previous work on Farm Bill history and political development (Coppess, 2018; Coppess, 2024).

Discussion

The modern Farm Bill coalition is built on four pillars consisting of the major mandatory spending policies which serve two constituencies on opposite ends of the food system from the production of commodities to food consumption. The four major policy pillars are farm payment programs (Title I), conservation (Title II), crop insurance (Title IX), and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps (Title IV). The first three provide direct assistance to a constituency of farmers, while SNAP provides benefits to low-income families and individuals to help with the purchase of food. The coalition can be a formidable political force, especially for the all-important vote counting efforts in Congress.

The coalition was built over many decades, in three significant stages. The basic farm coalition coalesced in the 1920s, achieving the first Farm Bill during the Great Depression in 1933 and adding crop insurance in 1938. The Food Stamp program was enacted in 1964. It was added to the Farm Bill in 1973. Conservation made a brief appearance in 1956 and was added permanently in 1985. Prior to the 2014 and 2018 Farm Bill reauthorizations, this coalition had not suffered a defeat on the House floor. It has not been defeated on the Senate floor and has compiled strong, bipartisan votes in that chamber during both of the contentious 2014 and 2018 reauthorization efforts.

While politically formidable, the Farm Bill coalition can be difficult to manage. It can also be tenuous, as recently demonstrated. Partisan pressures operating under constrictive budget laws and procedures have split the very different constituencies that exist in the Farm Bill coalition; farmers and SNAP households are vastly different in size and occupy opposite ends of the food system, as well as the poverty spectrum. According to the 2022 Census of Agriculture, fewer than 500,000 farms received government payments (USDA-NASS, 2022 Census of Agriculture, Table 6). By comparison, USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) reports that over 40 million Americans participated in SNAP on average each month (USDA-FNS, SNAP Data Tables). Farmers receiving federal assistance are increasingly larger and more sophisticated. These households generally have higher incomes, with median household incomes for commercial farming operations approaching $180,000 in 2022 (see e.g., McFadden and Hoppe, November 2017; USDA-ERS, Farm Household Income Estimates, November 30, 2023). SNAP eligibility begins at 130% of the federal poverty line, or roughly $20,000 for an individual and $40,500 for a household of four (U.S. Census Bureau, Poverty Thresholds). Budget law and procedures drive the partisan conflict, while ignoring the differences in constituencies and benefits. For example, the Congressional Budget Office February 2024 update projects that SNAP will spend 4 times ($1.15 trillion) the amount spent by farm programs, conservation, and crop insurance combined ($285 billion) over 10 years, while assisting between 70 and 80 times the number of constituents each month (CBO, February 2024).

As noted above, the closest historical analogue to the current era predated the modern coalition with food assistance and conservation policy. The years following the end of the Korean War (July 1953) featured a near-complete breakdown of the farm coalition over successive Farm Bills, beginning with the Agricultural Act of 1954. The breakdown was largely the result of a regional conflict between southern cotton interests, aligned with southern Democrats in Congress, and midwestern corn interests, aligned mostly with Republicans in Congress and the Eisenhower Administration. At the core of the conflict was a dispute over farm policy as it developed out of the Great Depression and World War II but collided with the post-war technological revolution that drastically changed farming. The conflict focused on the loan rates used to support crop prices but was fueled by the consequences of the corresponding acreage policies that were felt most directly by farmers. Chronic surpluses for cotton and wheat triggered reductions in the acres planted to those crops but farmers were allowed to plant alternative cash crops on reduced acres and many farmers switched to corn or other feed grains that spread surplus problems to those crops. The similarities with the current regional conflicts over statutory reference prices and base acres are notable.

During World War II, Congress had fixed price support loan rates at 90% of parity, a calculation comparing price and cost measures against a baseline relationship that existed prior to World War I. In short, this resulted in high, fixed levels of price support that could incentivize overproduction and cause surpluses of federally-owned-and-stored commodities because farmers could forfeit the supported crops if prices were below the loan rate (see also, farmdoc daily, January 9, 2020; January 24, 2020). Congress had extended this policy in 1952 during the Korean War. For the 1954 Farm Bill effort, President Eisenhower requested that Congress return policy to the flexible or adjustable loan rate calculation enacted in the 1938 Farm Bill that decreased loan rates when crops were oversupplied or in surplus. Southern Democrats in Congress, along with some Republicans, opposed but lost an amendment on the House floor that compromised by adding a modicum of flexibility.

A new Congress, with Democrats back in the majority, reconsidered the policy in 1955 under threat of a veto by President Eisenhower. Southerners on the House Agriculture Committee pushed through a return to 90% of parity but narrowly escaped defeat on the House floor in a bruising battle that featured an attempt to eliminate peanut support policy. The Senate Agriculture Committee chose to wait and, in 1956, President Eisenhower proposed the Soil Bank as an alternative that used conservation to address the worsening surplus problems. The Soil Bank concept had originated with farmers in Illinois but was opposed by the Southerners in Congress who pushed for 90% of parity and acreage provisions that corn farmers in the Midwest considered punitive. President Eisenhower vetoed the first version of the 1956 Farm Bill and forced Southerners in Congress to relent on loan rates and the acreage provisions.

After enactment of the Agriculture Act of 1956, which included the Soil Bank, Southerners in Congress retaliated by attacking the Administration and the program, including sabotaging its operation through cutting funds in the appropriations process. President Eisenhower abandoned the program in 1958 and it was terminated beginning with the 1959 crop year. In 1958, President Eisenhower again vetoed an attempt by Southerners in Congress to restore fixed loan rates, forcing a compromise that allowed corn farmers to vote themselves out of the program in 1959, which they did. With a new (and Democratic) president in 1961, Southerners in Congress retaliated by reconstituting a version of the acreage policy from the Soil Bank but applied only to corn farmers. They pushed it through Congress over Midwestern opposition (see also, farmdoc daily, June 26, 2020).

The next attempt by Southerners to push through farm policy opposed by the Midwest took place in 1962 and resulted in the first defeat on the House floor. Concessions to the Midwest for corn allowed the bill to pass but wheat farmers rejected the policy in a 1963 referendum, marking rock bottom for farm policy and the farm coalition. The following year, revisions to cotton and wheat policy had to be paired with votes on the Food Stamp Act of 1964 to be rescued in the House. Southerners on the House Agriculture Committee had blocked food stamp legislation repeatedly during this era and were facing increased retaliation from supporters of food assistance policy, which became a real threat once Southerners had pushed the farm coalition beyond its breaking point. The farm coalition’s breakdown coincided with a changing Congress and Democratic caucus that resulted from demographic shifts, Civil Rights legislation, and redistricting decisions by the Supreme Court.

Concluding Thoughts

History does not repeat but often recycles. The 2024 Farm Bill reported by the House Agriculture Committee recycles problems that plagued the previous two reauthorization efforts. It also recycles elements from an earlier era of coalition breakdown and Farm Bill failure. Both eras also expose notable tendencies of political factions that are worth exploring further, such as the pursuit of evermore absurd policy outcomes and the destruction of political coalitions. The full consequences for Farm Bill policies, however, remain unknown, awaiting histories yet to be written.

References

Coppess, J. "The Conservation Question, Part 5: Seeds of the Soil Bank." farmdoc daily (10):3, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, January 9, 2020.

Coppess, J. "The Conservation Question, Part 6: Development of the Soil Bank." farmdoc daily (10):13, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, January 24, 2020.

Coppess, J., G. Schnitkey, N. Paulson, K. Swanson and C. Zulauf. "Production Controls & Set Aside Acres, Part 1: Reviewing History." farmdoc daily (10):117, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 26, 2020.

Coppess, Jonathan. Between Soil and Society: Legislative History and Political Development of Farm Bill Conservation Policy (University of Nebraska Press, 2024) https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/nebraska/9781496225146/.

Coppess, Jonathan. The Fault Lines of Farm Policy: A Legislation and Political History of the Farm Bill (University of Nebraska Press, 2018) https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/nebraska/9781496205124/.

Hanrahan, Ryan. “House Ag Committee Advances Contentious Farm Bill.” Farm Policy News. May 24, 2024. https://farmpolicynews.illinois.edu/2024/05/house-ag-committee-advances-contentious-farm-bill/.

McFadden, Jonathan and Robert A. Hoppe. “The Evolving Distribution of Payments From Commodity, Conservation, and Federal Crop Insurance Programs.” U.S. Dept. of Agric., Econ. Research Service, Economic Information Bulletin No. (EIB-184). November 2017. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=85833.

Schnitkey, G., J. Coppess, N. Paulson, B. Sherrick and C. Zulauf. "Spending Impacts of House Proposal for Commodity Title Changes." farmdoc daily (14):96, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 21, 2024.

Wicks, Noah, Rebeka Alvey, and Philip Brasher. “Republicans score committee approval of farm bill with crucial Democratic backing.” Agri-Pulse.com. May 24, 2024. https://www.agri-pulse.com/articles/21149-republicans-score-committee-approval-of-farm-bill-with-crucial-democratic-backing.

Yarrow, Grace and Marcia Brown. “Farm bill markup aftermath.” Politico.com. May 28, 2024. https://www.politico.com/newsletters/weekly-agriculture/2024/05/28/farm-bill-markup-aftermath-00160062.

Zulauf, C., G. Schnitkey, J. Coppess and N. Paulson. "Are Changes in Cost of Production and Statutory Reference Prices Related in the House Agriculture Committee 2024 Farm Bill?" farmdoc daily (14):101, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 29, 2024.

Disclaimer: We request all readers, electronic media and others follow our citation guidelines when re-posting articles from farmdoc daily. Guidelines are available here. The farmdoc daily website falls under University of Illinois copyright and intellectual property rights. For a detailed statement, please see the University of Illinois Copyright Information and Policies here.